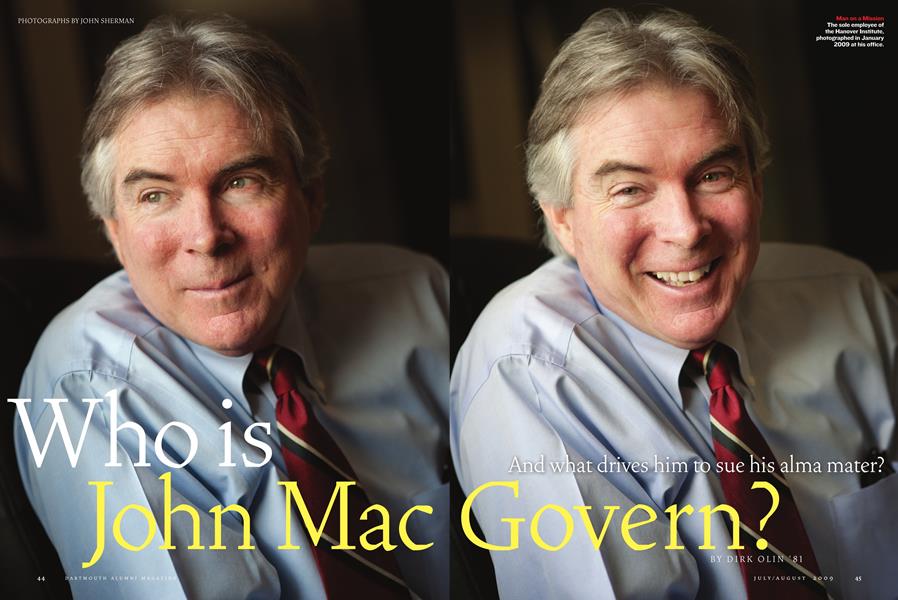

Who is John MacGovern?

And what drives him to sue his alma mater?

July/Aug 2009 Dirk Olin ’81And what drives him to sue his alma mater?

July/Aug 2009 Dirk Olin ’81And what drives him to sue his alma mater?

When the lawsuit that challenged Dartmouth’s board of trustees selection procedures was dismissed in June 2008, many observers assumed the bitter slugfest between conservative reformers and the College establishment had finally come to an end. But like Rocky Balboa (or Freddy Krueger from A Nightmare on Elm Street, depending on your point of view) the challengers persevered, with seven alumni filing yet another suit late last year. Their goal: to regain a higher percentage of alumni-nominated seats on a board that has expanded via internal appointment rather than contested election. (Alums vote to nominate some trustees; the board decides whether or not to seat them.) Whichever film protagonist provides the most apt metaphor, the executive producer of this drama, Hanover Institute founder John MacGovern ’80, presents one big bundle of contradictions.

A Republican insurgent who won an underdog race for the Massachusetts legislature in the 1980s, MacGovern nevertheless earned a reputation for ideological independence that included spurning his party leadership. An activist who for years has railed against a College administration he views as undemocratic and secretive, MacGovern funds lawsuits against the College through an organization that is all but opaque, as he enigmatically declines to reveal just how much of his enormous war chest was donated from non-alumni sources. And, though a self-described cofound- er of The Dartmouth Review who famously rejoined that cause a de- cade ago as chief fundraiser, he has since been excommunicated by that paper’s powers that be.

MacGovern founded the nonprofit Hanover Institute in 2002 to provide a locus for the governance reform efforts. He described his organization’s efforts during a lunch interview in the fall of 2008 (followed by a series of e-mail exchanges that dwindled and then went silent as my questions became more pointed): “The Hanover Institute believes it is good for Dartmouth to have many alumni involved in the selection of one-half the board of trustees. That is good for fundraising, good for the close bond between alumni and the College, good for the overall health of Dartmouth. For example, if alumni did not have the option to elect the four petition trustees recently elected I am convinced the war against fraternities, against Dartmouth football, against competition with hockey teams having an American Indian for a mascot and against The Dartmouth Review would have advanced much further. The voice of the alumni, expressed through its selected trustees, has made a difference. I also believe that questions raised about the effort to turn Dartmouth into a research university have been beneficial; that battle has not been won, but alumni awareness of what such a transformation would entail is beginning to awaken—and that is a very good thing.”

The institute’s sole employee, MacGovern maintains a modest Web site and public relations campaign. His fundraising, by contrast, has become positively gargantuan. According to tax filings, the organization raised $73,878 in 2004, $148,851 in 2005, $205,676 in 2006 and a whopping $838,117 during 2007. MacGovern’s salary that year was $63,500.

Defenders of the administration maintain that the institute was initially disingenuous at best—and furtive at worst—about its part in funding the litigation. But that question appears settled now, with MacGovern avowing his group’s financial backing for the suits. Because his organization’s agenda is also commonly perceived as a front in the wider education culture wars, however, a lingering, deeper, unanswered question informs the current twilight struggle. I had posed it to him over lunch. How much financial support has the institute received from non-alumni? His first answer was that “Ninety-nine percent of our contributors are alums.”

In subsequent correspondence I tried to make clear that I was curious about the amount of dollars donated (not the percent of donors donating). After a few weeks of delay came reply No. 2: “The vast majority of our contributions come from alumni.” Hoping that the third time would be the charm, I put the question again a few months later, as plainly as I knew how: How much money—in absolute dollars and as a percentage of the institute’s funding over the course of its life—has been donated by non-alumni?

During the lengthening pauses in our conversations, I researched MacGovern’s history. I conducted interviews with the players on all sides of the rancorous debate, with more than one observer citing MacGovern’s smarts and, especially, his tenacity.

But a different profile emerged from members of The Dartmouth Review with whom MacGovern had worked just before founding the institute. These were fellow travelers in the causes of conservatism, generally, and “parity” in college governance, specifically. And it gradually became clear why the question of institute fundraising would prove so thorny. That was precisely the role he had filled for the Review starting in 1999—and it had not ended well. As professor emeritus Jeffrey Hart ’51, who had served as Review chairman, told me: “John and I were friends for many years. No more.” The professor declined to elaborate, citing a confidentiality agreement that accompanied MacGovern’s severance.

At our meeting MacGovern related the political epiphany that led to his participation with the Review as an undergraduate. He had been sitting in Aquinas House in the autumn of 1979 when Greg Fossedal ’81 walked in and announced that The Dartmouth had ousted him as editor in a dispute over his conservative politics.

MacGovern, the product of a literally cloistered upbringing, was nearly a decade older than many of his schoolmates and had reached his senior year with an avowed detachment from much of mainstream college life. But this news plugged him in. “It was outrageous,” he recalled. “I was, on some matters, more liberal than a lot of them, but the intolerance and suppression of thought in what had happened was just too much. That’s what led to my participation with the Review.”

MacGovern did not join Fossedal on the Review’s editorial ramparts, but he raised money for the effort, a skill that would prove quite valuable out in the wide, wide world. Despite a soft-spoken and boyish mien, MacGovern after graduation forged a career that would lead naturally, perhaps inexorably, to his enlistment in the governance reform campaign.

During the early 1980s he took a brief turn in the public affairs office of Mobil Oil Corp. and as press secretary to a conservative challenger of then-U.S. House Speaker Thomas P. O’Neill. quently, after learning that a seat representing Harvard (the town, not the university) was opening in the Massachusetts legislature, he joined the fray on his own terms. With a history that included Shakers, transcendentalists and the breakaway communal sect in which MacGovern himself had been raised, the town offered an electorate at least somewhat more convivial to an independent conservative than other parts of the greater Boston area. Though far from a sure thing, MacGovern prevailed in a reportedly gritty campaign. As he would tell The Boston Globe in 1985, “Once I go to war, I don’t stop until it’s all over.”

Taking office in the fall of 1983, MacGovern quickly debunked his image as a right-wing martinet. He was one of a very few Republicans to spurn a rule-breaking power play by his party’s leader. He renounced his initial opposition to mandatory seat belts after becoming convinced that the law would save lives. He even garnered a reputation as an ardent environmentalist.

The last, perhaps, should not have come as a surprise. MacGovern was born in 1951, but he didn’t grow up in Jeffrey Hart’s 1950s. His childhood home, in fact, bore a striking resemblance to a hippie commune. Children wore robes, milked cows, tilled an organic farm. “The goal was to be totally self-sufficient,” MacGovern later recollected. “There was no contact with the outside; no newspapers, no radio, no television.”

But there was also no tie-dying of shirts, no burning of patchouli oil, no inhalation of illicit herbaceous combustibles. MacGovern’s parents belonged to the Slaves of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, a sect founded by a Jesuit activist (whom The Boston Globe called fanatical) who was ultimately excommunicated for preaching, among other things, that salvation was impossible outside of the Roman Catholic Church. MacGovern’s father died when John was a toddler, and his mother eventually became a nun within the order. Which might not have been as traumatic as it would have been in a secular context, given that the order’s common practice was to dissolve the parental bond early anyway.

“I’m not sure if my mother was raising me after 1955,” MacGovern told the Globe (also in 1985). As for the rest of his childhood environs: “It was like living in a boarding school,” he recalled. “My mother was one of the teachers.” The curriculum was rigorously classical—Greek and Latin, massive memorization assignments, logic and rhetoric. But it was not intended as preparation for engaging the outside world. “I was raised to stay there my whole life and never leave,” he said.

At 21, however, MacGovern stuck his toe in more worldly waters. Karen and Gerald Hartley Dodd Webster ’61, operators of a farm in the town, had been in touch with some of the commune’s youth through the years. They had made a standing offer to MacGovern, which he accepted in 1972, to live at their place. The next year MacGovern opted for fuller immersion, enrolling in a Catholic school in Rome. Eventually returning home, he decided on college, and Webster was a Dartmouth grad: Choice made. MacGovern majored in Chinese, “which I loved,” he told me, “but I never lost my belief in the greatness of Western culture.”

After four terms in the Massachusetts statehouse (and a turn as campaign adviser to Donald Rumsfeld’s 1988 exploratory bid for the GOP presidential nomination), MacGovern took aim at Congress in 1990. He was nearly successful, coming within two points of unseating Democratic U.S. Rep. Chester Atkins. He remained active in party circles, serving as Massachusetts cochairman of Indiana Sen. Richard Lugar’s 1996 presidential bid, and then re-engaged with the Review in the late 1990s. There he became lead fundraiser for the paper’s nonprofit parent in what he called an attempt to “expand” and “professionalize” the paper. It was an effort he abandoned after a few years, because, as he told me, “It’s ultimately a student paper and needs to remain that.”

Who abandoned whom, however, is an open question. A half dozen former Review staffers—who were not bound by the severance settlement and who worked for the paper during the days of MacGovern’s tenure—are critical of their former fundraiser.

“Revenue rose slightly, but expenses rose astronomically,” recalled Andrew Grossman ’02, a former editor who is now a senior legal policy analyst with the conservative Heritage Foundation in Washington, D.C.

Added a veteran of the Review’s business side who asked that his name not be used: “After a while it became clear that he had nearly bankrupted the organization somehow. So he was pushed out. And then he threatened to sue the paper for back pay. Get that? He pushed the organization to the brink and then threatened to sue for his own financial aggrandizement.”

One more insult was added to the injury, said former Review president Harry Camp ’04, now finishing up at the University of Virginia School of Law: “It’s very clear to me that he took the Review’s fundraising list. My father was a subscriber to the Review because I worked there. He has no other connection to Dartmouth. Yet now he’s been getting these solicitation letters from the Hanover Institute and John MacGovern.”

Presented with these allegations, MacGovern pronounced them all false but declined to go into detail, saying: “I have great respect for the overwhelming majority of students—by now hundreds of them—involved with the paper in its 28 years of existence. Among those have been a very few bad apples and I do not intend to battle them in the pages of the DAM.”

He added: “I have in my possession a letter from the board of the Review, written a few months after my resignation as president, praising my achievements-fundraising, number of issues published per term, and conservative speakers-during my three years trying to help the paper."

Informed of the allegations and MacGovern's denial, Review board chairman James Panero '98 said: "While I cannot comment on the Review's brief employment of Mr. MacGovern, I can say that the students who worked alongside him were among the Review's finest editors. They have a deep commitment to the trugh, and I've never known them to exaggerate."

However bitterly the Review period ended, one current Hanover Institute board member how could be reached for comment had nothing but praise for MacGovern. John Flitner '52 said he met MacGovern roughly "five or six years ago," after which he signed on to the insitute. The board meets "infrequently," he said, "often by telephone."

Asked about the Review stories, however, Flitner demurred. "I don't known about any of that," he said. " I do know that JOhn is good to work with. He's fair-minded. He's straght forward and courageous. And he's tenacious." On the other hand, Flitner seems to be something of an absentee landlord. "I don't ask for a breakdown of how our funds are spent or solicited." he said. "When we retain attorneys, I don't write the checks. But I know that one of our biggest expenses is litigation."

MacGovern insists that his current effort is completely separate from the Review. But, when asked by Human Events magazine in 2001 to explain the publication's prominence, event beyond the College, he seemed to provide connective rhetorical tissue to his present efforts: "The administration is dumber than the administration of Harvard or Brown," he said. "It's the administration's attacks that made the Review."

The critique of College administration that has animated petition candidates for the board of trustees is well known: a claim of mission drift from the school's historic commitment to undergraduate education, allegations of putatively repressive campus speech codes, the late President James Freedman's championship of "creative loners" and hardy perennial frets about frats and football.

Although petition trustee Stephen Smith '88 declined comment for this story, fellow petition trustee T.J. Rodgers '70 explained that the governance reform movement was not monolithic: "I first met John in 2004 after Dartmouth alumni elected me to the board. John has his own issues-he supports the Indian mascot for example-but he saw an open mind in me...I'd say John and I ended up disagreeing half the time."

Perhaps for that reason the Hanover Institute has trained its focus on process far more than policy. It helped win a battle to allow all alumni to cast ballots in Association of Alumni (AoA) elections, overturning the prior practice of requiring a voter's physical presence in Hanover for the vote. The much more bitter struggle, which continues to roil in the courts, turns on the issue of parity on the board of trustees.

Since the so-called agreement that was struck in 1891, half of the board's membership has been reserved for alumni-nonmiated seats, with the balance filled by board appointment. However, following consecutive victories by petition candidates (Peter Robinson '79 and recently deposed Todd Zywicki '88, in addition to Smith and Rodgers), the board in 2007 decided to expand by adding eight new trusteeships to be named by the board. MacGovern calls it "board packing," and it's hard to dispute that view. But in a plebiscite in 2008 alumni rejected the notion of suing the College over the matter, and even a couple of open governance leaders once allied with MacGovern say they're ready to move on.

"I too would like to see more alumni-nominated trustees," said John "J.B." Daukas '84, president of the Alumni Council. "But as seven out of 10 alumni do not even vote in trustee elections...I am sympatheric to concerns the board may have that a small minority of alumni can determine the fate of the College. It is the alumni's own fault in failing to vote that has brought us to where we are. The trustees I know are very independent and certainly not sheep-like followers of the administration."

JOhn Harrington '80, a New Hampshire attorney who provided counsel on the institute's incorporation but who has since left its board, basically allies himself with Daukas' view. "I'm reluctant to discuss this because John's a friend of mine and I don't want to say anything that would be viewed as hostile," he said. "But I was only concerned about trasparency and how meetings were conducted. I don't have a political ax to grind."

That the litigation was dismissed (with prejudice) only adds to the suspicions of John Mathias '69, president of the AoA, that subterranean forces are at work. According to Mathias, evidence points to a national conservative group providing considerable funding for the lawsuits. Frederic Fransen, executive director of the Indiana-based Center for Excellence in Higher Education (CEHE), acknowledged in a 2008 interview with The Dartmouth that he had established an account through a Virginia-based organization called Donors Trust at the behest of Dartmouth alumni eager to support the suit. (CEHE strives to stem what it calls a "decline in higher ed.")

Why wouldn't those alumni contribute in the open? "Many are afraid that their children or grandchildren might be denied admission by the administration because of their backing," said MacGovern. Why such donors would want any of their progeny to clamantis his or her vox in such a misgoverned collegiate deserto, MacGovern declined to explain.

How much support is coming from CEHE and Donors Trust? None of the players will say. But the Hanover Institute's most recent tax filing counts more than $493,000 in "indirect public support," far exceeding its roughly $345,000 in "direct public support."

The dynamic prompts Mathias to ask to what extent is CEHE "serving as a front for non-Dartmouth financing?" He added "Until full disclosure is made of this hightly material information, it is fair to assume that a substantail amount of non-Dartmouth money has been injected by the Hanover Institute into alumni politics and litigation against the College."

Trustee Rodgers offered a rejoinder: "I am not concerned about 'outside forces,'" he told me "I know some of the Dartmouth alumni-including myself-who supported the petition trustees and, guess what? I also know many of the Dartmouth alumni on the other side, who retained the Washington. P.R. consulting firm Edelman and Associates, which is well known for negative political campaigns. The most questionable money in the elections is likely to be the undisclosed millions in Dartmouth funds that were used both in trustee elections and the last Association of Alumni election." He did not elaborate.

Vice President for Alumni Relations David Spalding '76 disagreed with Rodgers. "I can't speak for those who've opposed the petition candidates, but the claim that the College has spent millions on alumni elections is simply not ture," he said. "However, Dartmouth has spent about $1 million defending litigation brought by supporters of the petition trustees that the great majority of alumni have clearly rejected."

MacGovern's attempt to dismiss the claim was more of a misdirection. "Some Dartmouth alumni prefer to contribute to the Hanover Institute through Donors-Trust," he said. "I know Fred Fransen and have great respect for what he is trying to achieve. But to suggest that any other group directs or influences the policies and actions of the institute is utter nonsense."

But given his Revew experience and individual history, I asked, aren't these legitimate questions to raise? "I do not wish to make the issue of alumni representation on the Dartmouth College board of trustees about John MacGovern," he said.

So what is the Rosebud sled in MacGovern's basement? Given his modest salary, the paycheck would seem an unlikely reason for his perseverance. More likely, it would appear, it is the innate doggedness-whether of the Rocky or Freddy variety-that he and others cite as so integral to his personality.

But if that trait has been called into the service of a campaign for clarity and trasparency in College governance, what about the percentage of the institute's out-side funding?

The third attempt was not the charm. MacGovern's final response was the same as it ever was: "Ninety-nine percent of contributors are Dartmouth alumni; percentage of contributions whould be less."

Man on a Mission The sole employee of the Hanover Institute, photographed in January 2009 at his office.

DRIK OLIN is a contributing editor.

MacGovern maintains a modest Web site and PR campaign. But his fundraising has become positively garantuan.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

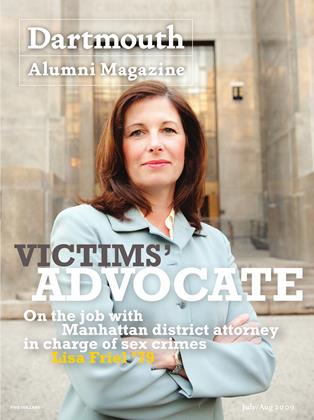

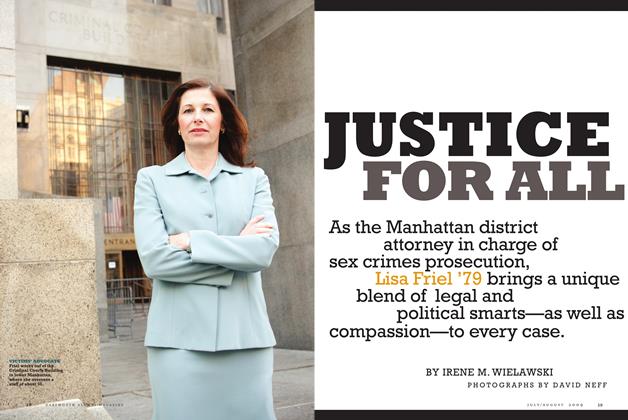

Cover StoryJustice for All

July | August 2009 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Feature

FeatureIn Too Deep

July | August 2009 By PETER HELLER ’82 -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEThe Skipper

July | August 2009 By Sarah Tuff -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

July | August 2009 By BONNIE BARBER -

FILM

FILMLife’s Big Questions

July | August 2009 By Lauren Zeranski ’02 -

ALUMNI OPINION

ALUMNI OPINIONTime for a Bigger Tent

July | August 2009 By Ed Gray ’67, Tu ’71

Dirk Olin ’81

-

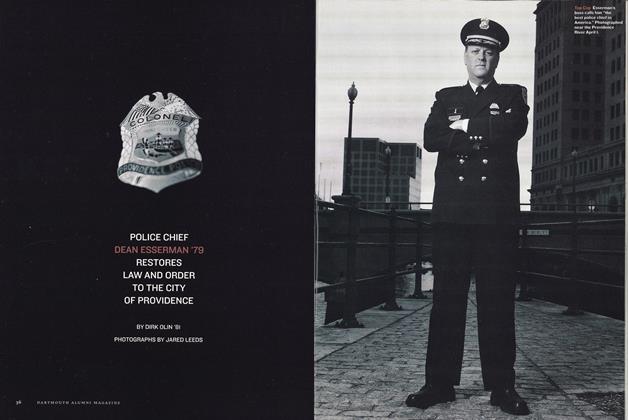

Cover Story

Cover StoryPolice Chief Dean Esserman ’79 Restores Law and Order to the City of Providence

July/August 2005 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

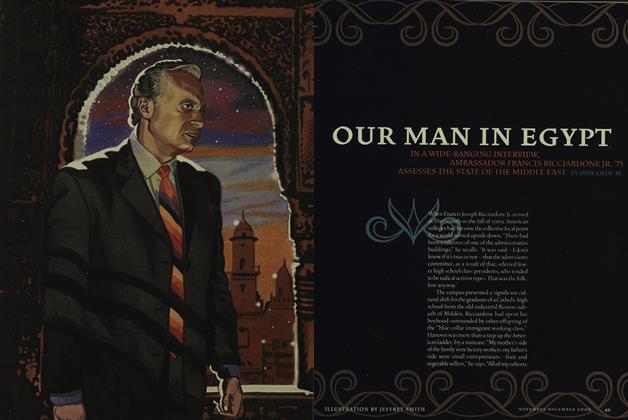

Cover Story

Cover StoryOur Man in Egypt

Nov/Dec 2006 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Cover Story

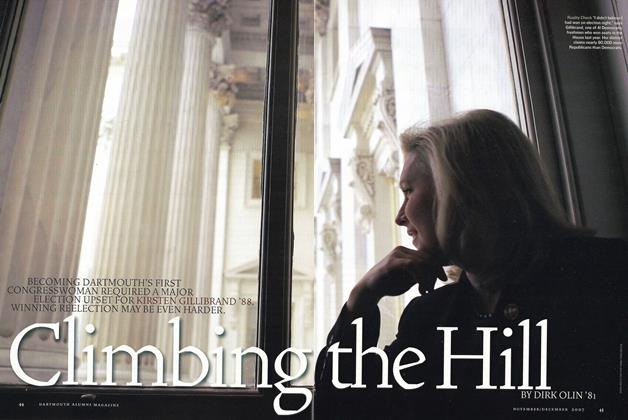

Cover StoryClimbing the Hill

Nov/Dec 2007 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Cover Story

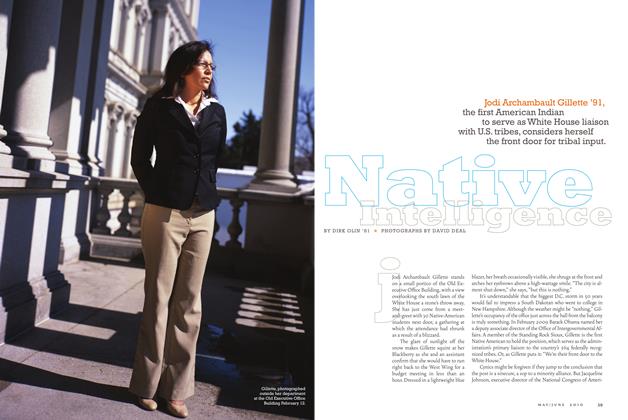

Cover StoryNative Intelligence

May/June 2010 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

FeatureThe Reluctant Luddite

Sept/Oct 2011 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Article

ArticleSpecial K

MAY | JUNE By Dirk Olin ’81

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryPassing With A Roll Of The Dice

MARCH • 1987 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

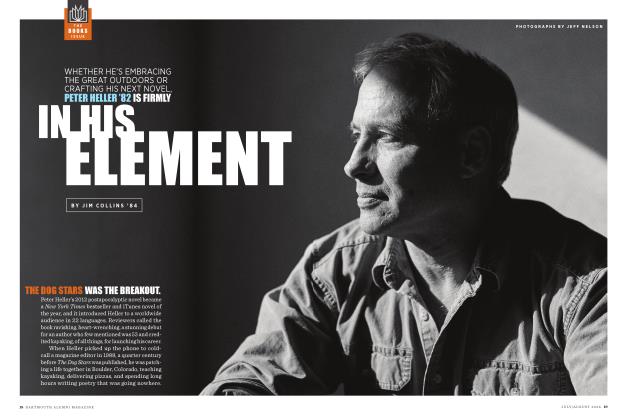

FeatureIn His Element

JULY | AUGUST 2024 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

Sept/Oct 2007 By Kristine Keheley '86 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"Are the fireflies ghosts?"

OCTOBER 1985 By Priscilla Sears -

Feature

FeatureHomely Truths

JUNE 1983 By S.G. -

Feature

FeatureNine to Midnight (or two if hot)

March 1979 By Shelby Grantham