While rummaging through some old boxes the other day, I uncovered a little black book that brought back memories of my friend Pierre Kirch and certain pleasant evenings last spring. The little black book is entitled The GreatGuest Supper Society.

The idea first came to mind while Pierre and I stood on the shoulder of Interstate 84 in Connecticut. It was an early spring day with little wind and lots of sunshine. We were hitchhiking from Hanover to New York City. Between rides, one of us would sit on his backpack and read the newspaper while the other thumbed passing cars. After finishing the paper, we took turns reading to one another from Hemingway. This soon grew tiresome because it was difficult for the reader to make himself heard over the roar from passing tractor-trailers. So we talked.

We talked about women, books, hitchhiking, the weather. Then we turned to a favorite, and often amusing, subject: what we would have our ideal lives be like. Perhaps talks of ideal lives should stop at an age earlier than 20, but one feels the need to dream at times, especially on warm spring days when hopes run high with the change in the weather.

Pierre began by saying that the evenings in his ideal life would be most important. He would like to come home from work to his wife and children. The children would dine before the parents, attend to their schoolwork, and bid an affectionate good night. Then Pierre and his wife would dine together by candlelight with music and wine. They would clean the dishes, dance slowly to some soft music, then drift off to tender love-making and sleep.

I made a mental note to myself that the evenings Pierre had described probably had no basis in reality, but unable to improve on their romance and simple beauty, I had nothing to add. The mention of dining reminded Pierre and me that we would be cooking and eating dinners together for the coming three months. We had just finished a winter-term Outward Bound course in which the 14 of us who lived together had a communal meal each evening. But that was over, and Pierre and I were the only ones of our congenial social group willing to commit ourselves to dining together each evening during the spring. Both of us felt that dinners meant more than just slapping a tray down in the line at the dining hall and wolfing food prepared by other people. Dinner should be a great event a time to relax and share food, conversation, impressions, anecdotes about our days. Dinner might even be considered an essential part of one's education if it included a selection of interesting and informative guests who could be coaxed to share much more of themselves over a fine meal than they ever could in an office or a classroom. We were seeking a kind of education that went beyond the classroom.

Perhaps it was because the hitchhiking had tired me, or maybe it had to do with getting close to the city, but an impulse caused me to stop all these silly musings and say something cynical like, "All of that sounds nice, but let's not talk about it anymore because none of it will ever come true and it's depressing to keep going over it. Okay?" Pierre disagreed-vigorously. He conceded that maybe all of his ideal life might not come true, but some parts stood a chance. And why not start with our dinners? Why not have candlelight? And music? And wine? Perhaps it all sounded a little contrived at that point, but my friend's enthusiasm won me over, and somewhere on 1-95, just north of New York City, The Great Guest Supper Society was born.

We had heard about the Great Issues course given at Dartmouth during the fifties and early sixties. Pierre and I looked at each other and repeated under our breaths, "Great Issues? Great Guests? ... Yes, Great Guests!" We had our name. We had stationery printed. Three other students asked to join our supper society. Over a pitcher or two of beer at a local pub, Pierre and I drafted the first of a great many invitations.

According to the tenets of Pierre's ideal life, our dinners took place around a large dining table to the tune of soft music and with candlelight and plenty of wine. We had a shortage of chairs, so that with the sofa moved in from the living room and the trash can moved in from the kitchen and turned over to serve as a stool, our meals sometimes resembled a Roman feast set in a tenement apartment where the electricity had been cut. But candlelight covers a mul- titude of small anomalies, and the wine made everything seem just fine. Our guests ranged in age from nine months to 90 years, in occupation from poets, professors, and students to townspeople, businessmen, and deans. We were seeking a different kind of education-and we got it. It was one made up of life stories and relaxed conversations, of questions asked and answers given-the kind of exchanges that can only happen in a candlelit room, late at night, seated around a table before an almost empty bottle of wine. Some guests stayed to talk until after midnight, some played music for us after dinner, some showed us films they had made, and others read their poems. We entertained 87 guests in 73 days.

We kept a guest journal wherein our guests were required to write short entries before leaving. One of my favorites was written by our Outward Bound instructors: "Well, well, well. . . pass the bottle! Who's the only major-league player to make an unassisted triple play? Pass the bottle . . .

and well, what is this California scene? And what about the politics of rape? Pass the bottle ... It sure is good to feel the strength of friendships continuing after a transient phenomenon has passed. Good feelings and not enough time ... the story of my life. Thanks, guys.-Tim." And: "It's so fine to feel the greatness of friendship, though I have only known these guys for a short time . . . high quality even- ing-lots of controversy that is exciting and challenging! . . . must get together in another setting . . . early breakfast and off to see the sunrise? Thanks-'til early morning.-Patsy."

Well, Pierre has graduated, but four of us continue to cook and eat together several nights a week. Sometimes we eat by candlelight, sometimes we drink wine, always we play music, and often we share our meals with a guest or two. And I still have our Great Guest Supper Society stationery, which bears an epigram of former dean Arthur Jensen: "You come here for four years and you get so you can ask the right questions and then you find that nobody-but nobody-knows the answer."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMaking Books

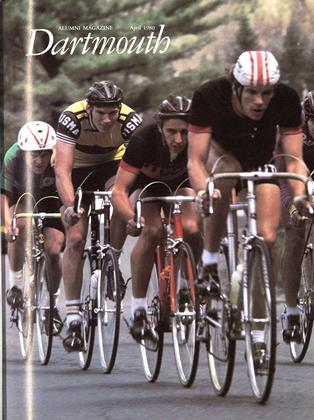

April 1980 By Robert H. Ross -

Feature

FeatureLife in High Places

April 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureExtra Credits & Bonus Points

April 1980 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Article

ArticleWho in Hell Was Jeff Tesreau?

April 1980 By Edward D. Gruen '31 -

Article

ArticleAdapting to the Heights

April 1980 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1963

April 1980 By DAVID R. BOLDT

Michael Colacchio '80

-

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

JAN./FEB. 1980 By Beth Ann Baron '80, Michael Colacchio '80 -

Article

ArticleThe Bard's American Friend

September 1979 By Michael Colacchio '80 -

Article

ArticleZombie of the 1902 Room

October 1979 By MICHAEL COLACCHIO '80 -

Article

ArticleAn Old-fashioned Mutant

December 1979 By MICHAEL COLACCHIO '80 -

Article

ArticleAlchemist in Miniature

May 1980 By Michael Colacchio '80 -

Books

BooksExperiential Education

OCTOBER 1981 By Michael Colacchio '80