Recent events and minority issues

IN response to a student proposal drafted jointly by members of the Interfraternity Council, the Afro- American Society, Native Americans at Dartmouth, the Latino Forum, Women at Dartmouth,* and supporters of an equal access admissions policy, Dartmouth's faculty voted to reschedule classes on March 8 to permit a full day of what the administration termed "organized discussions devoted to an exploration of the fundamental issues regarding race relations which have been raised by events on campus over the past several weeks." Students called it Moratorium Day and arranged a two-hour "Forum on Recent Events and Minority Issues," including in their program speakers against sexism as well as speakers against racism. The morning forum, held in Webster Hall, was followed by a full afternoon of open discussion in small, moderated groups.

Hard on the heels of March 8 came exams and the end of winter term, followed by the usual end-of-term exodus from campus, and no accurate assessment of Moratorium Day can as yet be made. It is possible, however, that for many a participant, the forthrightness, candor, considerateness, and cooperation experienced on March 8 will turn out to be among the most significant events in his or her Dartmouth education. Family disagreements are particularly difficult to articulate and resolve; and if Moratorium Day was successful in convincing the participants that, in the words of Gail Frawley '79, "the well-being of your fellow members of the Dartmouth community depends on you and your ability to perceive their needs," an important and difficult lesson in humanity has been learned.

The episodes which led to Moratorium Day - episodes that reflect the high feelings about racial and sexual equality that have been running in recent times throughout the country and especially on college campuses - accumulated at Dartmouth like fragments of kindling. Late in February, they were touched off by an incident at a hockey game. In the blaze of indignation that followed, the various minority factions on Dartmouth's campus joined together in an unusual and prophetic coalition to call for a family meeting with the white male majority. Seen in its best light, the meeting was an attempt to foster sympathetic perception of minority needs and assets. The goal was a mutual understanding that might open a community some feel is often provincial and hidebound to a broadening and enriching cosmopolitanism.

It is difficult to choose a starting point in recounting the episodes that led to Moratorium Day, but they date back at least to the beginning of winter term.

January 15: The Dartmouth published an advertisement announcing that Playboy magazine was "scanning the Ivy League for a cross section of women for the upcoming September 1979 issue." Playboy photographer David Chan was quoted in an interview in The Dartmouth as offering "$100 for clothing, $200 for semi, and $400 for nude."

January 16: Women at Dartmouth, a student organization, set up an information table in Hopkins Center and distributed posters around campus protesting Playboy's attempt to reduce to the status of sex objects Ivy League students "who are supposed to represent some of the best minds in the country." On that same day The Dartmouth showed itself unsympathetic to this interpretation of the incident by running two cartoons ridiculing Dartmouth women as beefy female jocks too unattractive to interest Playboy anyway.

February' 9: Two peaceful demonstrations took place on campus in the punishing subzero weather of Winter Carnival weekend. A crowd of 300 gathered for a "Convocation on the Green" in support of an admissions policy disallowing consideration of sex. Another group of some 60 students gathered in front of Parkhurst Hall for a mock funeral service in symbolic protest of the College's investments in companies doing business in South Africa. These demonstrators, part of a nation-wide student movement against complicity with apartheid, marched solemnly to Cutter Hall, home of Dartmouth's Afro-American Society, where a black casket ornamented by a gold cross was placed in an ice-sculpture cemetery of six graves.

February 22: Another rally was held on the Green, attended by some 200 students supporting an admissions policy of equal access and the "integration of women and minorities into the mainstream of College life." The crowd marched to the Collis student center, where the Trustees' Committee on Students Affairs was meeting, and presented a petition for equal access signed by some 2,000 students. The demonstrators also requested an open meeting with the entire Board of Trustees. In the evening, several Trustees held with some 50 students an informal meeting during which both student and Trustee tempers flared over the question of equal access.

February 23: A Buildings and Grounds crew went out on a post-Carnival cleanup mission and swept into its dump trucks the crosses of the symbolic graveyard in front of Cutter Hall. When students complained to the foreman about the dismantling of the scene, he apologized for having mistaken the graveyard for debris, called the truck back from the dump, and returned the materials. No other snow scene was disturbed at that time by the crews, and some students and faculty harbored suspicions of ill-feeling on the part of some B&G truck drivers, and some even wondered about administrative prejudice. On that same day appeared in The Dartmouth an inflammatory cartoon depicting Women at Dartmouth as a scruffy dog trotting slyly between two fire hydrants, one labeled Playboy and the other "Admissions Policy/Ratio."

February 25: During the crowded Dartmouth-Brown hockey game at

February 26: At a regular meeting, the faculty approved a statement "that the faculty deplores the use of the Indian symbol and the instance at last Sunday's hockey game, and urges the administration to investigate this matter." President Kemeny called the incident "horrendous and in the worst possible taste."

February 27: Some 150 students marched at noontime to protest College policies on investment in South Africa, the status of the Black Studies Program at Dartmouth, and minority admissions policies. Marchers called for "true support" for blacks on campus and protested the dismantling of the South African graveyard snow scene. Late that same afternoon, the two "Indian" skaters and their getaway driver gave themselves up to the Dean of the College. In the evening, student supporters of equal access at the College met and drafted a statement proclaiming their goal as "sex-blind admissions with adequate recruiting to bring up the number of female applicants for the Class of 1984." The statement said also that increased recruitment of women "in no way mitigates the College's responsibility to minorities" and cautioned against "any ploy to pit one minority group against the other."

February 28: The College Committee on Standing and Conduct (CCSC), after deliberating for two hours, voted to suspend for the remainder of the winter term the three students involved in the skating incident. All three would thereby lose academic credit for the entire term. During the night a window in the reception room of President Kemeny's Parkhurst office was smashed by a hockey puck thrown from outside the building.

March 1: The three suspended students appealed to the President. Moved by the sincerity of their expressed desire to persuade others that the Indian symbol is deeply offensive to members of the community, the President overruled the CCSC, changing the students' suspension to college discipline with restrictions for one year and promising to waive even that penalty at the end of the spring term should the efforts made by the three warrant it. Amid rumors that the President had "pardoned" the three students, Lenny Pickard '80, president of Native Americans at Dartmouth, called President Kemeny's action "a slap in the face for the Native American community" and said it was "the most heinous and racist act any president of Dartmouth College has ever committed."

March 2: During a welcome spell of Warm weather, a noontime rally to protest racism was held in the center of the Green, organized by Native Americans at Dartmouth, the Afro-American Society, and the Latino Forum. Some 200 students and faculty gathered around the deteriorating central snow sculpture and listened to speeches explaining that the huge white mass was being taken as' symbolically representative of the "all-white" values of the Dartmouth community. Members of Native Americans at Dartmouth, the Afro- American Society, and the Latino Forum wrote on it their organizations' initials in red and black spray paint, in order to emphasize their desire to be "an intricate and accepted part of the community." The 200 demonstrators then joined hands around the sculpture and sang "We Shall Overcome."

That same afternoon, President Kemeny issued a public statement calling for calm and for an end to inflammatory rhetoric. He also met briefly with a representative of the Afro-American Society and at the end of the day for a longer period with Native Americans at Dartmouth. That group requested, as a symbolic act, that Dartmouth show its good faith by moving the Hovey Grill murals, suggesting that the murals - which depict semi-nude and drunken "Indians" - be moved out of the context of eating and entertainment and set up elsewhere to be viewed as art and history. The President agreed to ask the Trustees to consider the request and promised to close Hovey Grill in the meantime.

March 4: A rescheduling of classes was requested by the student coalition, which thus set in motion Moratorium Day, March 8, 1979.

President Kemeny spoke first on that day. He urged the audience of 1,000 to work hard at communication. "The most important ingredient in true communication," said the President, "is listening." He concluded his remarks with a plea: "I beg you to keep your perspective. Surely the overall welfare of this college, a very special college, is more important. I know that most of you, even at the time when you are most bitter, deeply care for and love the College. And I assure you that this college, through its faculty, its administration, and its Trustees, deeply cares about you." The President then left the stage and the auditorium. (Before the meeting, he told the organizers that he had to leave after his speech, but no one mentioned this to the audience - an oversight that caused renewed distress.)

Judith Aronson '82 of Women at Dartmouth was the first minority speaker. "What is it to be a woman at Dartmouth?" she asked. "There is a 3-to-1 ratio here and still a quota on admissions. There are only five tenured women faculty members, none of whom is black or Native American. The other day the snow sculpture commemorating those who died in South Africa was removed. It was a so-called blemish on the campus unfit for Trustees' eyes. But the breasts made every year in front of Sigma Nu have remained, an unquestioned Dartmouth tradition.

"As a result of an investigation of sexist practices at Dartmouth, more and more women are coming forward with reports of sexual harassment by male professors and students - incidents ranging from verbal harassment to gang rape."

Referring to a letter from Dean Manuel to The Dartmouth, Aronson said, "Dean Manuel recognized that it was not his prerogative to decide what is or is not honorable to Native Americans at Dartmouth. Likewise, it is not a male's prerogative to decide what is or is not offensive to women. We are offended by the breasts at Sigma Nu. We are offended by Playboy's solicitation of our bodies. Pornography is the theory to which rape is the practice. It does not matter if you do not understand why we are offended. It should be enough that we are offended. Educate yourselves. After seven years of coeducation, we are tired of being 'coeds.' We are students."

Aronson also made several demands of the College on behalf of Women at Dartmouth. They included equal access and active recruitment of minority women; expansion of the Women's Studies program; commitment to a real affirmative action policy for women, especially minority women; a crisis facility and grievance procedures for rape and other forms of sexual abuse; a re-evaluation of all tenure decisions in the last two years, including that of Professor Joan Smith (who has charged Dartmouth with sex discrimination in tenure decisions); free day-care facilities; a women's athletic program comparable to that of men at the College; justice and sensitivity from The Dartmouth; and the changing of the words of the school song. "We are not 'Men of Dartmouth,' " concluded Aronson.

Aronson was followed on the podium by Latin American student Marco Grados '82, representing the Latino Forum. Grados testified to having encountered at Dartmouth "a cultural isolation I did not expect," which led him to examine the status of Latinos in this country. He found, he said, that they constitute a full nine per cent of the population of the United States, "generally in the lower strata of society, under-represented, generally second-class citizens." Grados had been "shocked" to discover that less than one per cent of the student population at Dartmouth is Latino. He looked at the commitment to Latin American studies made by other Ivy schools and found Dartmouth "backward" by comparison. "The element of understanding of Central America and South America is missing at Dartmouth," said Grados.

Racism was also the subject of the following speaker, James DeFrantz '79, president of the Afro-American Society. "Racism at Dartmouth, and for that matter, in America," he said, "exists on two levels: individual and institutional. Numerous examples of individual racism can be cited without any trouble. Institutional racism is very deeply woven into the fabric of American society and as such is much more difficult to recognize. It is a teaching process by which Americans are taught to believe in the inherent inferiority of the black person in particular." DeFrantz cited as the most obvious forms of institutional racism at Dartmouth a "lack of hiring of black faculty, staff, and administrators in decision-making positions, admissions policies that do not allow a representative cross-section of Afro- Americans to be admitted, and - most important - a curriculum which all but denies the contributions, culture, or even the existence of the black person in America or elsewhere. These are examples of institutional realities that help to make Dartmouth a living hell for black students and for minority students in general. Individual and institutional racism work together to create a truly hostile environment for those who do not fit into the traditional mold - that is, white male Anglo-Saxon Protestant. They combine to convey a strong message to black students: You are not wanted here." DeFrantz said that students at Dartmouth are still not learning about people of other cultures and summed up by stating, "Education from an exclusively white perspective is.only half of an education."

Lenny Pickard '80 and Gemma Lockhart '79 then spoke for Native Americans at Dartmouth, recounting the history of the College's nine-year-old Native American Program and then making again the group's statement on the Indian symbol, a statement first made in 1974: "The Indian symbol and associated traditions are insensitive to the cultures of Native American peoples. The Indian symbol is a mythical creation of a non-Indian culture and in no manner respects the basic philosophy of Native American peoples. Dartmouth College was granted a charter in 1769 by George III with one of the primary objectives of the charter being Indian education. However, from 1769 to 1971, Dartmouth graduated only 20 Native Americans. Dartmouth has for some 200 years only nursed a romantic notion of being an Indian school. This is particularly apparent in the creation of the Indian mascot in the 1920s and subsequent caricatures of the Native Americans. It is said that these Indian symbols represent pride and respect, yet pride and respect do not lie in caricatures of people. It is deplorable that such traditions exist within an institution ostensibly committed to the education of Native Americans. We are adamant in our belief that Dartmouth College must discontinue any and all forms of racism. Consequently, we encourage the Dartmouth community to cease further use of the symbol and related traditions. We also emphasize our sincere hope of achieving an atmosphere of genuine understanding and mutual good faith between cultures."

The last speaker was Professor of English William Cook, who defined radical action as efforts to change the standards of an institution. "But much of the protest we've experienced in the last few years," he maintained, "has not been radical as I've defined it. It has sought not to change the institution, but to convince it, even to force it to draw closer to the standards it purports to hold dear. Dartmouth College is committed to providing equal access to its facilities to both men and women, to a broad liberal arts education, to an educational environment in which blacks are not made to feel that by the nature of their race they are inferior, and to an environment where Native American peoples are not made to feel either insulted or exploited. Dartmouth is committed to making itself an institution in which varied racial, ethnic, religious, and gender groups give and receive in an atmosphere of mutual trust and respect. I see nothing radical in insisting that Dartmouth College live up to these commitments."

Questions from the floor ranged from bewilderment as to why President Kemeny had not remained to hear other speakers to inquiries as to the existence of black separatism on campus and requests to hear from minority faculty members. Then the forum broke for lunch, to reconvene at one o'clock in small groups moderated by aculty and administrators. There participants discussed not only the issues brought up during the morning, but related issues as well, such as the appropriateness of the anger felt and shown by members of Women at Dartmouth, the differences between the skaters incident and the red- and-black paint demonstration, and the pain and hurt felt by the builders of the snow sculpture when to the sun's destructive work were added red and black initials.

During the course of the sometimes acrimonious discussions, several white men spoke feelingly about the surprising and enriching effect the taking of a Black Studies or a Native American Studies course had had on them. They had not known what was there, they said, and the courses stood out sharply for them as high points in the Dartmouth experience.

*Of the sponsoring organizations, the Interfraternity Council represents the 24 fraternities and sororities on campus, with a combined membership of about 1,300 out of an enrollment totalling 4,068. The Afro-American Society has about 300 members; there are 285 black students currently at Dartmouth. Native Americans at Dartmouth has a membership of 31; there are 42 Native American students enrolled. The Latino Forum has 15-20 members; the Latino enrollment (based on Spanish surnames) is 19. Women at Dartmouth has a membership of about 150; the current female enrollment is 1,144. Most of these organizations include adult members.

Shelby Grantham is an assistant editor andstaff writer for the ALUMNI MAGAZINE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThere and Back Again

April 1979 By John S. Major -

Feature

FeaturePilgrims' Progress

April 1979 By L. Bruce Anderson, Edward Bradley -

Article

ArticleJust Out of Reach

April 1979 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleBooks in Process

April 1979 -

Article

ArticleMoney Man

April 1979 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleOn the Raising of Spirits

April 1979 By MICHAEL DORRIS

Shelby Grantham

-

Feature

FeatureWomen at the Top (almost)

May 1977 By SHELBY GRANTHAM -

Feature

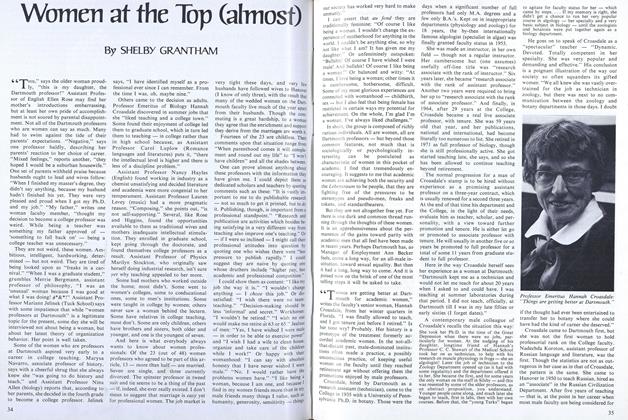

FeatureRich and tasty cabinetwork

March 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureFirst Five Months

DECEMBER 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

Feature'One day it came to me: sherry for breakfast was a good idea.'

MARCH 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThe Attraction of Peanuts

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureBONFIRE!

OCTOBER • 1986 By Shelby Grantham