THE signs identifying what campus study areas would be open around-the- clock during summer term's exam week appeared two weeks before the term ended. They reminded me that the real term — those last two frenetic weeks when often more than half the work for an entire course must be completed — had only just begun. For those who still had the bulk of their academic work to complete, stopping long enough even to read the signs might mean they wouldn't finish their work on time. Not finishing on time meant either failing or spending half a week in interim housing, trying to finish a take-home exam or crank out a last paper when everyone else had already left Hanover.

Life in the 24-hour study areas, like the 1902 Room in Baker Library where I spent exam week, -often proved educational and sometimes even interesting. A certain camaraderie developed among the early- morning crowd who continued studying past 2:00 a.m. The five or six survivors exchanged occasional quips to help keep one another awake as the mornings wore on. Sometimes outsiders helped to lighten the fatigue. A streaker came through one morning at about 3:00 a.m., and friends occasionally brought caffeine products from the snack bar at Thayer Hall. And 4:00 a.m. gossip about two inconsiderate students who all week had monopolized a table meant for ten, polluted the air with their chain-smoking, and disturbed everyone with their loud and incessant jabbering, could always instill new life in the group.

Each morning at 5:00 a man from Buildings and Grounds would come to clear away the wreckage — dozens of empty coffee containers and soda cans, overflowing ashtrays, and wads of crumpled-up papers strewn over tabletops and floors. He worked methodically, making clean sweeps of each tabletop with a big broom, pushing the debris into a carefully positioned garbage can. He not only restored a sense of order, he also had a wealth of detailed information about weather conditions on the outside. Depending on his advice, I sometimes went for walks down to the crew dock to enjoy the hour before the sun would rise and burn the mist off the river.

My daydreams in that hour spent lying on the dock often focused on the glories of sleep. In the mist I could pretend I was really dreaming, so that refreshed, I could tolerate a return to the 1902 Room until Lou's Restaurant opened its doors for coffee and blueberry muffins. Or, if I had no money, I could wait for the Dartmouth Savings Bank to open and then have "complimentary" coffee and doughnuts. Running into a hungry professor, dean, or fellow student there is not uncommon, but professors, and deans usually take just doughnuts because they get coffee at their offices.

Back at my books, lack of sleep eventually would overwhelm me. I don't often snore, so I didn't feel self-conscious about passing out in the library for a couple of hours. I discovered some very comfortable sleeping positions that required only a chair, books, and a tabletop for props. My favorite position involved placing my right arm with the elbow bent across my pile of books. I could then rest my face half on the forearm and half on the upper arm, leaving plenty of space in the crease of the elbow for even the largest nose to fit comfortably. The only drawback was sometimes waking up to find that I had drooled a bit on my books and smudged my hard-won notes.

In this fashion I managed to average three or four hours of sleep a day. After a few days of this I began to experience some effects of sleep deprivation. First, I noticed the complete loss of nervous energy — I could sit perfectly still for a long time. Surprisingly, my ability to concentrate got better, probably because I became oblivious to all but the loudest noises and distractions. Of course, my appearance deteriorated, and each day the lines under my eyes grew darker. In short, I eventually turned into something of a zombie. I quickly learned how to keep my eyes open, however, by creating short-lived highs with exercise. A two- or three-mile run followed by a quick dip in the Connecticut River could provide enough false energy for three or four hours of nearly normal functioning. The ensuing crash, however, usually defeated even the most valiant efforts to do without sleep — at least for a day or so.

Unfortunately, such haphazard sleep habits have not been limited to exam periods. For many undergraduates, they have become the normal pattern. A friend and I agreed that we would remember this past summer as "the summer of no sleep." We might reasonably be accused of hyperbole, but averaging three or four hours of sleep per night really counts for no sleep at all. One might also argue that sacrificing sleep is unnecessary, but for some of us it is the only way to accomplish all there is to do in order to maintain the illusion that we are well-rounded individuals who lead balanced lives.

Those of us who have chosen to be chronic insomniacs look forward to the breaks between terms when we attempt to cram three months of lost sleep and relaxation into three short weeks. For the first week or so, in an orgy of celebration, we average even less sleep than during the term. Such forgotten luxuries as afternoon naps and reading the Sunday New York Times, first page to last (starting with "Arts and Leisure" and skipping "Business and Finance"), take on great importance during the second week of vacation. The third week brings the true test of relaxation: overcoming the compulsion to read the Sunday New York Times at all.

Just when sleeping for nine continuous hours has been relearned, a new term begins and doing without all but four hours a night must be mastered again. I've been told that's not how college used to be, although I suspect, for some, that's just not true. I returned to Hanover this fall to find that the 1902 Room will now be open around-the-clock, not just during exams, but all term long.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

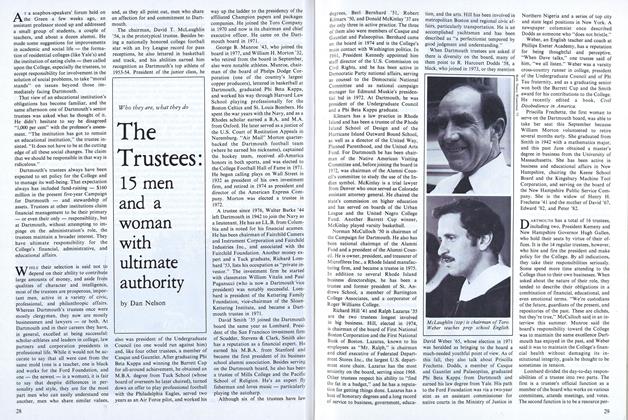

FeatureThe Trustees: 15 men and a woman with ultimate authority

October 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

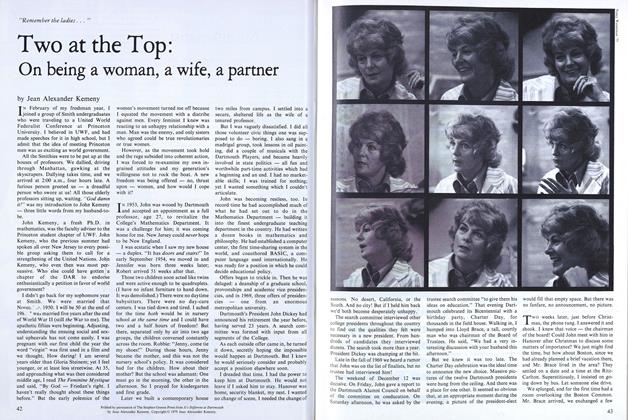

FeatureTwo at the Top: On being a woman, a wife, a partner

October 1979 By Jean Alexander Kemeny -

Feature

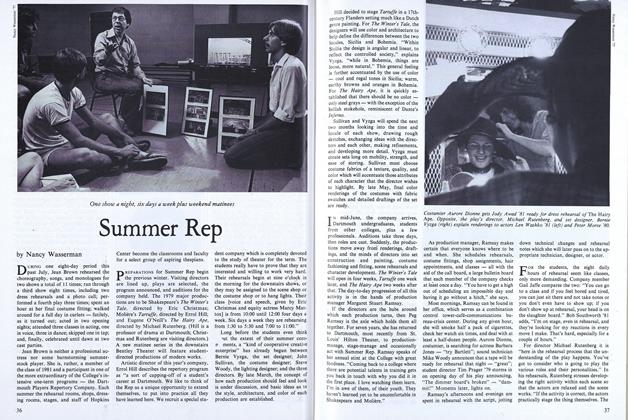

FeatureSummer Rep

October 1979 By Nancy Wasserman -

Article

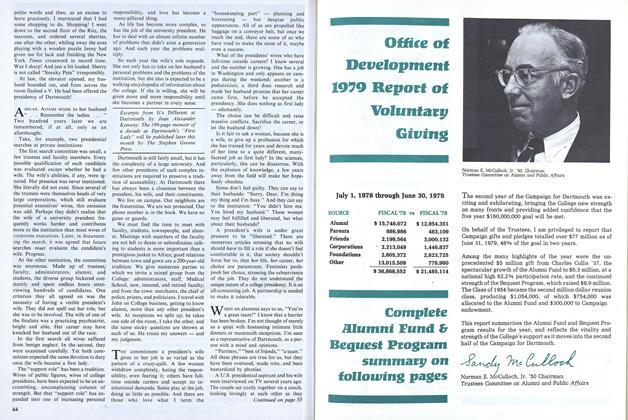

ArticleOffice of Development 1979 Report of Voluntary Giving

October 1979 -

Article

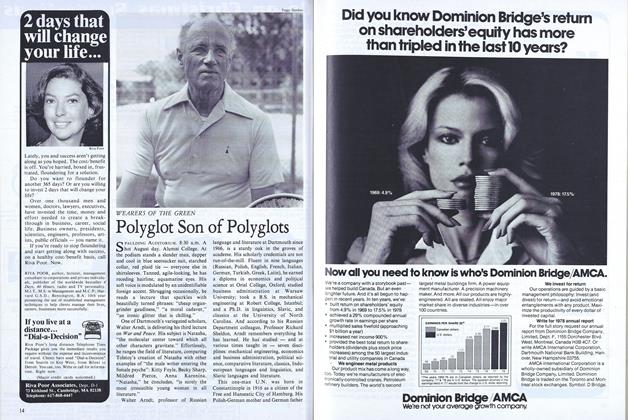

ArticlePolyglot Son of Polyglots

October 1979 By NARDI REEDER CAMPION -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

October 1979 By JEFF IMMELT

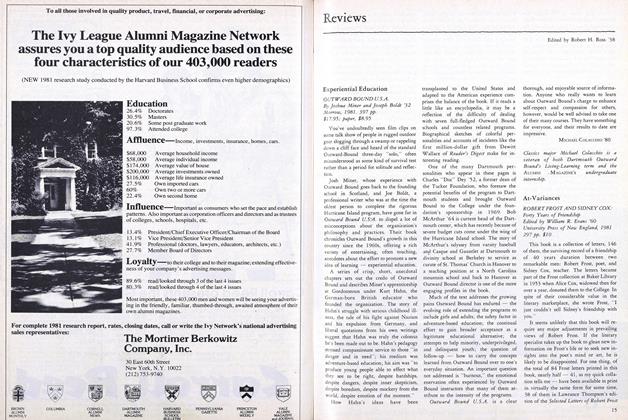

MICHAEL COLACCHIO '80

-

Article

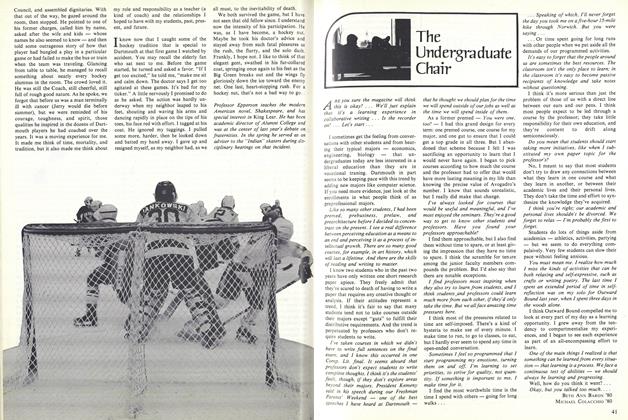

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

JAN./FEB. 1980 By Beth Ann Baron '80, Michael Colacchio '80 -

Article

ArticleAn Old-fashioned Mutant

December 1979 By MICHAEL COLACCHIO '80 -

Article

ArticleThe Five-Year Plan

December 1979 By MICHAEL COLACCHIO '80 -

Article

ArticleThe Great Society

April 1980 By Michael Colacchio '80 -

Article

ArticleAlchemist in Miniature

May 1980 By Michael Colacchio '80 -

Books

BooksExperiential Education

OCTOBER 1981 By Michael Colacchio '80

Article

-

Article

ArticleOUTING CLUB'S MEDAL GIVEN TO COL. GREENLEAF

February 1920 -

Article

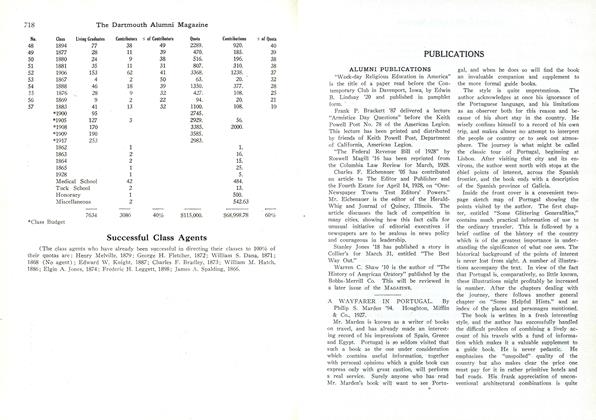

ArticleSuccessful Class Agents

JUNE, 1928 -

Article

ArticleCouncil Elections

May 1936 -

Article

ArticleSills '42 Edits 17-Volume Social Science Encyclopedia

MAY 1968 -

Article

ArticleA Leader in Modern Home Design

November 1934 By of Richard H. mandel '26 -

Article

ArticlePurpose of the College

June 1940 By The Editor