TAMARA NORTHERN and I met on a women's studies hike to the top of Mt. Cardigan. She kept having to slow down for the rest of us. At the end of the hike, one of the group turned suddenly and said to the rest of us, "Oh! You must all go and see Tamara's new exhibition! It's wonderful!"

So I did. The exhibition, admittedly wonderful, was mounted at the Dartmouth College Museum in Wilson Hall and entitled "The Ornate Implement: African Knives, Swords, Axes, and Adzes from the Collection of Frederick and Claire Mebel." At one point, I passed a door marked "Tamara Northern, Curator of Anthropology," and the thought crossed my mind that I didn't really understand what being a curator meant. I finished looking at the exhibition and then knocked on Northern's door in hopes of finding out.

She opened it dressed in piain black set off by a belt of primitive beadwork and a pair of obviously authentic high-button shoes. Under a pixie haircut shone a pair of very young and intense dark eyes. She bowed me into the tangerine-colored office with a kind of old-world charm, and then held me spellbound for three hours while she explained how collectors work, how African art collecting was born, what museology is, and what curators do.

Mounting exhibitions, it turns out, is one of the most important and the most difficult things that curators do. Exhibitions take, according to Northern, anywhere from six months to two years to put together, and it is through them and the catalogues prepared about them that significant contributions to the field are made by curators of anthropology who are, apparently, a self-effacing lot. They bestow tremendous amounts of energy and long hours on the exhibitions mounted in their museums, but their names are never directly attached to them (except on hikes). Northern has mounted no fewer than ten in the College Museum since she began to work here in 1975.

To explain the genesis of the Mebel exhibition (by way of example), Northern began with a bit of autobiography. Born and raised in "a small provincial town" in central Germany/she had teachers who impressed upon her that there was a very large world outside her little town. "As I approached intellectual maturity," Northern said, "I wanted to know more about this world. I wanted to know how other human beings dealt with life, and in my long talks with my teachers, I became aware of anthropology as a way to satisfy that curiosity."

She studied anthropology at Gottingen and later at the institute established by anthropologist Leo Frobenius at Frankfurt University, where, as the German equivalent of a "work-study" student, she was assigned to categorize Frobenius' Exzerptur, or field research file. "It was a collection of handwritten entries Frobenius had made from all over the world, his research notes, and one of the categories he himself had noted was 'lron in Africa.' That intrigued me, because he also noted that the status of the worker in iron in most parts of Africa was different from that of anyone else in the community." Northern had already been drawn "instinctively" toward the art of the central African republic of Cameroon, and when she discovered that Cameroon was also one of Africa's principal iron manufacturing areas, her interest in the metal work of Africa was first sparked.

After working in New York for a while, at the American Museum of Natural History and the Museum of Primitive Art, Northern realized that, although Americans had become principal investigators of African art, the art of Cameroon a highly significant tradition of wooden sculpture and mask-making was largely unknown in this country. "All the primary literature about the area was in German," she explained. "Cameroon had been a German colony from about 1890 until the end of World War I, when Germany lost it. Colonial officers' official records, the papers of German explorers and traders, and other such accounts yielded a great deal of data about the art and traditions of Cameroon. It was not available to most of the scholars, since Americans have become increasingly more restricted in their use of other languages. I knew about the material. I knew the language. It was splendid art. And there I was." She began to specialize in the art and the social organization of Cameroon, while her interest in African metal work simmered on a back burner because, academically speaking, its time had not yet come.

Northern went on to explain that the bulk of African art we know of comes from the 19th century. Most of it is wooden and perishable. In the late 1950s, African objects began being collected on a large scale as manifestations of artistic expression, and the sixties were the hey-day of African art collecting, when New York was flooded with African "runners" carrying huge burlap bags containing everything under the sun (most of it made yesterday for sale in New York).

In the late seventies, though, the quality wood sculpture began to give out, and now, according to Northern, the field of African art studies is ripe for an examination of the iron work of the continent (evidence of work in iron dates from as far back as 700 B.C. in some parts), as well as an investigation of the larger picture of iron technology there. She herself began a couple of years ago to think in terms of mounting an exhibition of iron artifacts with aesthetic as well as functional qualities a sort of "iron sculpture" exhibition; and when she encountered the African collection of Claire and Frederick Mebel '35, she saw in it the opportunity to put one together. The Mebels, who had exhibited at Hopkins Center from their Western fine arts collection, were agreeably anxious to exhibit also from their African collection. A loan was negotiated.

The rules of exhibition-borrowing require that the borrowing institution arrange for packing, transportation, and insurance of the items being loaned, though the loan itself is refreshingly gratis. Northern and her assistants filled a van with boxes and puffy plastic padding and drove off to the Mebels' home in New York, where Northern selected the pieces she wanted (in some cases she was not at all certain yet exactly what they were). Back at the College, they were carried up to the large-windowed workroom above Northern's office, spread out on various tables and "curated."

Curating, according to Northern, means not only identifying artifacts and objects but also finding out what they stand for, what they mean, what they express about the web of relationships within a culture: "A particular object can offer an entry into the diverse realms of anthropology and art history, ecology and the indigenous technology of a people. When you work with material culture, with the actual physical witnesses of another culture, there is an element of authenticity present that investigations of a different, purely intellectual nature lack."

Northern spent months studying the objects from the Mebel collection, comparing them with photographs of similar objects in books and catalogues and using her long experience with things African to suggest places and dates of origin, functions, and interpretations of imagery. "I re-attributed some 90 per cent of what went into the exhibition," she explained. "That was an unusual amount of basic curating to have to do, but authoritative identification is a large part of the work behind any exhibition. A curator must verify every attribution before she or he passes it on to the public." She went on to point out that this is where the generous lender profits. The objects come back from loan fully documented, and their fame and monetary value increase with greater legitimization.

After her final selection of the iron implements, Northern conferred with Malcolm Cochran, the museum's exhibition designer, about such things as display stands, background colors, and spatial arrangements within the galleries. The clustering of the objects in the available space is vital, Northern feels, to exhibition-making as opposed to shop-shelf displaying: "The whole notion of exhibition relates to space. The viewer and the object share the space, and it is important. Collectors often want you to put more stuff into the 'empty' space. But one must not ever crowd things. I remember an exhibition at the Museum of Primitive Art, which had three separate galleries on one level. In the first gallery, the chief curator put one object with a statement about the exhibition. It was very startling, and it carried the whole point of the exhibition in emblem."

An exhibition, Northern continued, is both an aesthetic whole and an assemblage illustrating the concept in the curator's mind, and the objects themselves must carry the concept: "If words must carry the message, something went wrong." The concept behind the Mebel exhibition has to do with the special qualities inherent in metal, which, Northern feels, lead to the imbuing of metal implements with institutional and personal authority and power. Many of the implements in her exhibition are weapons, and as such, she feels, they manifest our most negative and destructive cultural feature; however, they supercede this dimension in their testimony to human creativity, ingenuity, and the drive to infuse with artistry whatever we make. (This concept is verbalized in the pamphlet Northern composed to describe the exhibition; but one can appreciate best the awesome tension between terror and beauty that it articulates by looking at the exhibition itself.)

One of the first questions curator and designer asked themselves after conferring as to space was, "How can we use the cubes?" The cubes are 25 three-foot plywood boxes each topped by a clear plastic cover two feet high. Northern designed them when she first came to Dartmouth, basing their size on the average dimensions of the materials in the collection. A wide variety of exhibition designs can be made by combining cubes along multiple axes. What they cannot accomplish with the cubes, the museum staff deals with in-house for the most part, turning out wrought-iron knife stands or mounting blocks or transparent shelves curved to fit particular objects as called for by the designs.

"By and large," observed Northern, "we are very economical. I think the Mebel exhibition required some $l50 in installation materials. The most expensive item in it was the life-sized mural photograph showing Pa Tih, Babungo ironworker, at his forge. We had that enlarged in Boston, for $300, though we mounted it here to save transportation and mounting costs."

Even fake walls are raised sometimes (and attached so precisely to the real ones that it is very difficult to tell that Wilson Hall was not built that way), identification labels and explanatory paragraphs are printed up, the exhibition title is devised and hand-lettered both on the gallery wall and on the signboard outside, cloth is cut for backdrops, paint chosen for the cubes, things glued and pinned. The same feverish flurry of last-minute fixings and cleanups occurs just before an exhibition opens that happens backstage on opening night in the theater.

"Mounting an exhibition is something that includes an act of magic," mused Northern. "After all due consideration of what one wants to do, when there is an assemblage of objects on three or four tables, or on the floor suddenly, as you look at them, they produce an exhibition. Everything falls into place, and they become more than their sum. It's very, very rewarding."

This 19th-century royal sword, from Benin-Dahomey, was carried as a parade weapon.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureLove and War Among the Ivies

January | February 1981 By Keith Bellows -

Cover Story

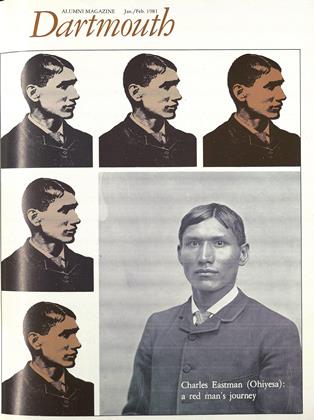

Cover StoryStranger in the Land

January | February 1981 By Rob Eshman -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

January | February 1981 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1965

January | February 1981 By ROBERT D. BLAKE -

Article

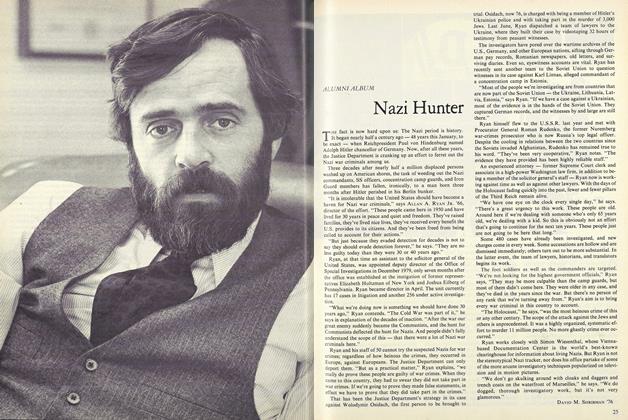

ArticleNazi Hunter

January | February 1981 By David M. Shribman'76 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

January | February 1981 By JACQUES HARLOW

Shelby Grantham

-

Feature

FeatureMen and Women: What's the Difference?

OCT. 1977 By Dan Nelson, Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureJohnny can't write? Who cares?

January 1977 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureWomen at the Top (almost)

May 1977 By SHELBY GRANTHAM -

Feature

FeatureThe Researcher and the Teacher

November 1978 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThe big eye in Arizona

SEPTEMBER 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureShaping Up

SEPTEMBER 1983 By Shelby Grantham