NEGOTIATING PEACE: WAR TERMINATION AS A BARGAINING PROCESS by Paul R. Pillar '69 Princeton University Press, 1983. 282 pp., $25.00

The changing perspectives since

World War II on the role of the military in promoting national interests are clearly delineated in this scholarly and carefully written book by a political analyst with the CIA. Where earlier, national interests were primarily thought of as being secured through diplomatic processes with military action brought in as a last resort, this book focuses on how military action is utilized today to influence the course of diplomacy itself. While using military force in this way is hardly new, seeing the military as a primary actor in diplomacy is.

Pillar points out that nations today are likely to go to war sooner and stay in longer, apparently against their own national interest, than in earlier times. They are also less likely to capitulate than before, with the result that long and costly wars between intensely hostile antagonists do after all have negotiated endings. Pillar's explanation of this change in war-making behavior is two-fold: 1) the web of international politics has fewer seams so that states "feel" geographically remote actions as directly inimical to their well-being; and 2) a sense of national righteousness is on the increase everywhere, reducing the chances that any state will back down in a disagreement. Since wars must be successfully brought to termination if the war system is to continue, this new intransigence creates problems.

Pillar has written this book to help policymakers become more sophisticated in their use of military pressure during war termination negotiations. He uses five case histories to illustrate the use of force during negotiations: the War of 1812, the Korean War, the French-Indochina War, the French-Algerian War, and the U.S. involvement in Vietnam. The dilemmas of negotiation come out very clearly in the case histories. In the face of incompatible diplomatic "offers," concessions must be made, yet making concessions is a sign of weakness that must be avoided. By analyzing negotiations in terms of stages, Pillar identifies critical points at which one side might manage a concession without appearing weak. Not surprisingly, in the end both parties have to bargain and compromise in a fashion familiar to labor mediators in order to satisfy some interests of each party.

Pillar is knowledgeable in the field of peace research and industrial disputes. The chapter on "The Dynamics of Concession" draws effectively on relevant concepts from these fields. The analysis of the phenomenon of the disparities of perception between parties of what a conflict is about is excellent. The discussion in the ensuing chapter of using the "military instrument" to make conflict prolongation so expensive for the enemy that quick concessions will be won has ironic overtones for the reader since Pillar has already pointed out in the previous chapter that this doesn't work.

Pillar is a good analyst and recognizes the limitations to the effectiveness of military action in achieving diplomatic goals. He also recognizes the economic and social costs of such action. His advice to diplomats on negotiation strategies in the chapter on

"The Manipulation of Multiple Issues" is solid. The main task of the book however is to "rationalize" the militarization of diplomacy, and Pillar stands by that rationalization in his closing chapter. Because this is an honest, scholarly, and clear-thinking piece of work, however, the book can also serve as the foundation for a serious re-examination of the military-diplomatic nexus and for the construction of alternative non-military strategies for the pursuit of international security.

ELISE BOULDING

Professor Boulding, the chair of the sociology department at the College, hasbeen deeply involved in the study ofpeace, and in organizations concernedwith peace research, for many years.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePsycho-Social Dynamics and the Prospects for Mankind

December 1983 By Charles E. Osgood '39 -

Feature

FeatureMaris Bryant Pierce: A Seneca Chief at Dartmouth

December 1983 By Howard A. Vernon -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCROSSROADS

December 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

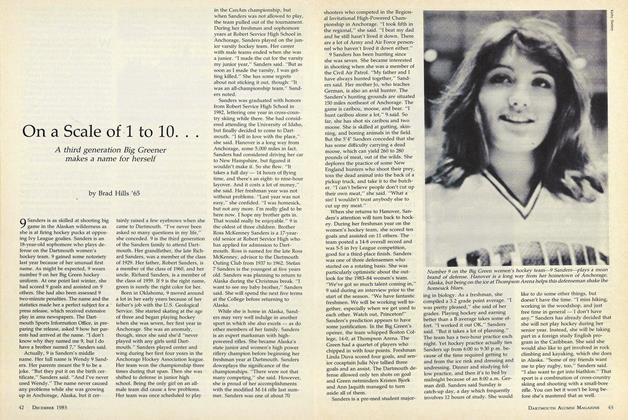

FeatureOn a Scale of 1 to 10...

December 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Feature

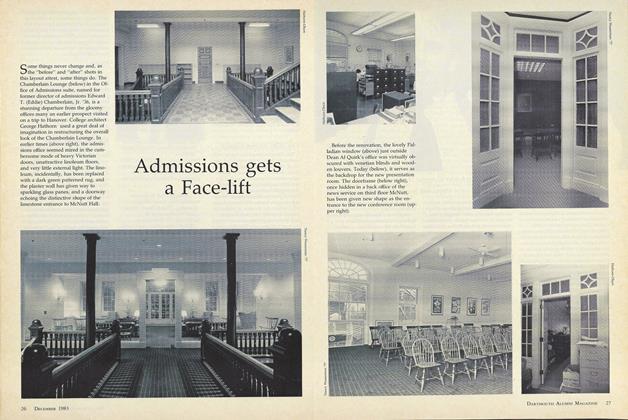

FeatureAdmissions gets a Face-lift

December 1983 By Nancy Wasserman -

Sports

SportsSports

December 1983 By Kathy Slattery

Peter Smith

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

October 1980 -

Article

ArticleHello, Mr. Chips

March 1980 By Peter Smith -

Feature

FeatureQuestion: Who are the Arts for and, Indeed, Who Owns Dartmouth?

April 1981 By Peter Smith -

Article

ArticleEndings and Beginnings

JUNE 1982 By Peter Smith -

Books

BooksWords of Wisdom

MAY 1984 By Peter Smith -

Article

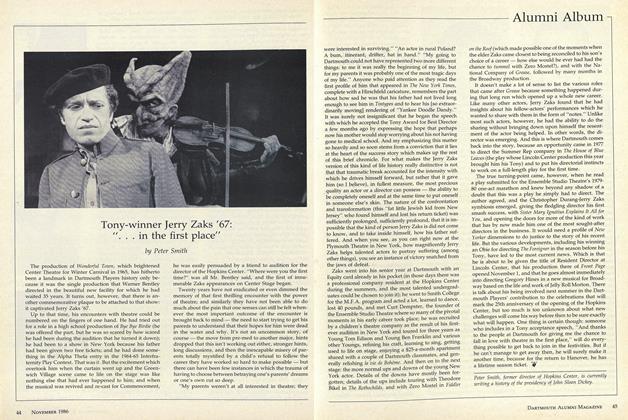

ArticleTony-winner Jerry Zaks '67: "...in the first place"

NOVEMBER 1986 By Peter Smith

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE COX FAMILIES OF HOLDERNESS

June 1939 -

Books

BooksTHE CALIFORNIA 2000 CAMPAIGN: THE POPULIST MOVEMENT WITH A MEANING FOR ALL AMERICA.

October 1974 By JAMES C. WICKER '21 -

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN SWITZERLAND.

JANUARY 1965 By KENNETH R. DAVIS -

Books

BooksShelf life

Sept/Oct 2003 By Matt Feinstein '04 -

Books

BooksNEUROLOGY AND PSYCHIATRY FOR GENERAL PRACTICE

May 1951 By NIELS L. ANTHONISEN, M. D. -

Books

BooksDEVIANT BEHAVIOR AND CONTROL STRATEGIES.

February 1975 By RAYMOND L. HALL