A day with Sandra Day O'Connor

"It used to be a hit-and-run affair having distinguished speakers come to Hanover," President Kemeny said in 1979 when he announced the College's first formal fellowship for visitors. "We picked them up at the airport, took them to their audience, and then loaded them back on the plane again. The Class of 1930 Fellowship provides an opportunity for the speaker to get to know Dartmouth, and vice versa."

Established by the members of the Class of 1930, the fellowship brings well-known figures to Hanover for two or three days to deliver a major address and meet extensively with students. All associated expenses are covered by the fellowship, which also carries an honorarium of $1,500. John Sloan Dickey was the first 1930 Fellow, and since then, Margaret Mead, Saul Bellow, Andrew Young, Maria de Lourdes Pintasilgo, and Lane Kirkland have graced the podium in that capacity. The latest in this stellar series was United States Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, who was at the College April 9-10.

O'Connor answered her first Dartmouth question over buffet lunch in the new Rockefeller Center for the Social Sciences. "How long have you been in Hanover?" "Twenty minutes," she replied. Nine hours later, after lunch, two receptions, dinner, and a speech, she was still answering them. The last one, "How do you manage time?" received an equally forthright answer: "I don't do it very well - except to go the Supreme Court and work. I've given up doing much else."

She is a handsome woman, taller than the average, reserved, ladylike, and somewhat cool in public. In the flesh she seems more fragile than her newspaper photographs suggest. She has fine gold-gray hair and blue eyes, and she made her appearances at Dartmouth clad simply but expensively in muted and neutral colors. Oddly at variance with the rest of her feminine appearance were the rings she wore, two massive gold ones of the kind traditionally reserved for men - the only outward manifestation of the steel that must certainly underlie the porcelain.

Her evening address was historical and tastefully studded with statistics, some of the more intriguing of which were these: Since its constitution in 1790, the United States Supreme Court has had a total of 102 justices. The number of people on that bench has varied, according to the attempts of various presidents to pack it or to prevent some specific nomination. Originally a six-member board, it changed to five, then seven, then nine, then ten, then back to seven, and finally, in 1869, to nine, where it has remained. Only three presidents - Harrison, Taylor, and Carter - have not had the opportunity to nominate a justice. As for tampering with the court, Harry Truman seems to have had the last word on that, according to O'Connor, who quoted him: "Packing the Supreme Court simply can't be done. I've tried it and it won't work."

O'Connor was most interesting in her more private conversations, especially with the students, to whom she warmed visibly. They tried - unsuccessfully - to pin her to several walls and in the end settled for discussing her own career, about which she was generously open.

O'Connor, who graduated third in her class at Stanford Law School, explained how she got into public law: "I couldn't find a job in the private sector after graduation. All I got was an offer as a legal secretary." She came to love public law, she said, in all its branches. After graduating in 1952, O'Connor became a deputy county attorney in California, then spent some time in private practice, next became assistant attorney general for Arizona, four years after that served as a senator for the State of Arizona, in 1975 became an Arizona county superior court judge, and finally moved up to the bench of the Arizona Court of Appeals, whence she was recruited in 1981 by President Reagan for the highest court in the land.

"In the executive branch, as a county and state attorney," she told the students, "I loved getting involved in things, looking into the state mental hospital and so forth. Being a legislator had its challenges - the phone rang from 6 a.m. to 11 p.m. and I made 15 speeches a week. That was grueling, and some of the big problems you encounter there are emotionally depressing. In the judicial branch, it is the opposite: you see the everyday legal problems - domestic relations, juvenile crime, torts, what's really bothering people. Sitting on a trial bench is like watching the soaps all day: I heard stories so bizarre they wouldn't be on the soaps. People say wonderful things. All sorts. The bad part of that was that you were restricted to what the attorneys brought you - you couldn't pick up the phone and call Doctor X to find out what he thought."

Students also wanted to know about her marriage. "Rearing children is a major problem when you both have careers," she explained. "The hard part is summers, when there's no school. I did it with a series of sitters for my three boys, absolutely fabulous young men who took them ice-skating, to the zoo, played football with them - everything you love to do with an older brother. When they were not available, the children visited my parents on the family ranch. I did the cooking." Here she caught her husband's eye and smiled. "John is marvelous, but not in the kitchen."

Attorney John Jay O'Connor, the justice's husband, was with his wife during all of her appearances at the College. A dapper man, grayhaired and blue-eyed, he wore a dark suit and a blue tie and identified himself as the chairman of the male auxiliary of the United States Supreme Court. He also was asked about the marriage.

"Although our marriage may seem atypical statistically and to you," he explained, "it seems normal to us. I couldn't imagine being married to a woman not my educational equal. It is a vehicle toward additional shared humor. That's the great treat. That's what makes greater education for women not just an economic benefit - it broadens them so they can play all sorts of instruments."

"What is life like as the spouse of a Supreme Court justice?" asked the students. "It's a full life," he replied. "My lord - she's the highest-ranking woman in American history, and everywhere she goes, the question is, how big is the hall? And she's asked to every function in Washington. Last night we were with the President, Weinberger, Mel Clark. That's the fun of it. You meet the people who run the world and find out they are just folks too. The biggest problem is finding time for our friends."

The delicate questions Justice O'Connor answered deftly, if not reflectively. Will we ever see a woman as President? "Sure." Will she get there via the vice-presidency or election? "By the vice-presidency first." Will the Equal Rights Amendment give more power to the courts? "It would give us a new framework in which to address allegations of gender discrimination. We don't know what the effect would be. Now, there is only mid-level scrutiny of gender discrimination, which hasn't been looked at as seriously as racial discrimination. Things pass muster under gender discrimination that would not hold up in cases of racial discrimination."

Asked about case overload, O'Connor expressed the opinion that people in this country rely too much on the courts to resolve all manner of disputes. "We need some alternative dispute mechanisms to take whole subjects - business arbitration, domestic relations, torts - out of the courts."

To students seeking advice about law school, O'Connor said, "There are too many lawyers in the country today. The competition is very intense, and I would not encourage anyone who was not very sure of what he or she wanted to go to law school." To those who are determined to go into law, she recommended a career in public law.

One disarmingly blunt student asked, "Did you feel qualified when you were appointed?" O'Connor replied patiently that there had indeed been "a question in my mind as to whether I could adequately fulfill that incredible assignment." "And now?" the student persisted. The justice smiled and handed it right back. "The jury's still out," she said.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFeast and Famine

May 1984 By Laurie Kretchmar '84 -

Feature

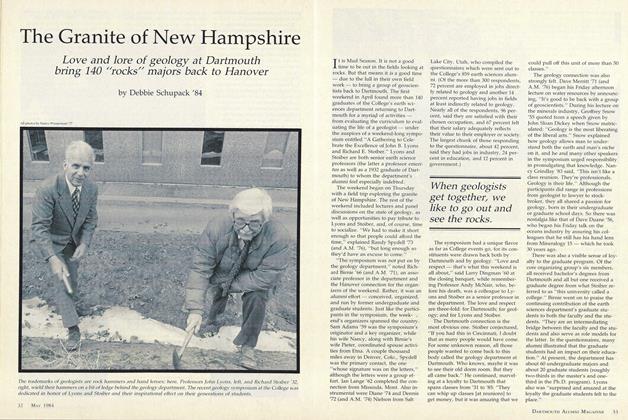

FeatureThe Granite of New Hampshire

May 1984 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Return to Dartmouth

May 1984 By Brian W. Ford '67 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

May 1984 By William G. Long -

Class Notes

Class Notes1956

May 1984 By Clement B. Malin -

Class Notes

Class Notes1979

May 1984 By Burr Gray

Shelby Grantham

-

Feature

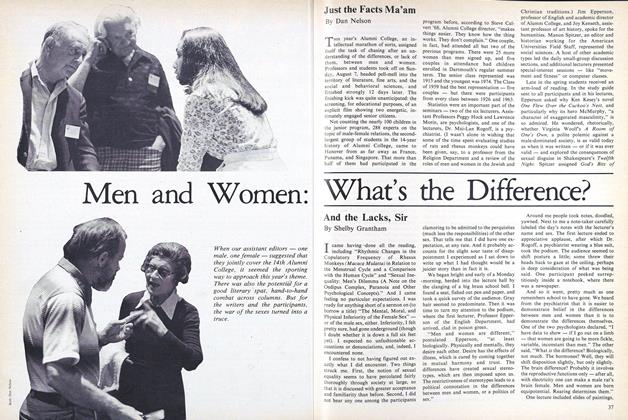

FeatureMen and Women: What's the Difference?

OCT. 1977 By Dan Nelson, Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureWomen at the Top (almost)

May 1977 By SHELBY GRANTHAM -

Feature

FeatureNine to Midnight (or two if hot)

March 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureShaping Up

SEPTEMBER 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

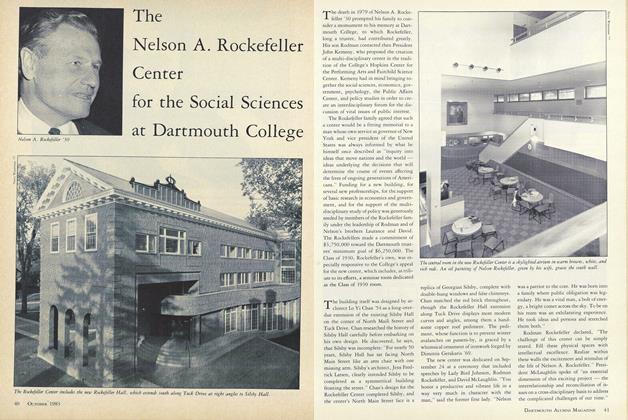

FeatureThe Nelson A. Rockefeller Center for the Social Sciences at Dartmouth College

OCTOBER, 1908 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureIntimate Collaboration

MARCH • 1985 By Shelby Grantham

Features

-

Feature

FeatureLessons from the Past

OCTOBER, 1908 By Allen A. Ryan '66 -

Feature

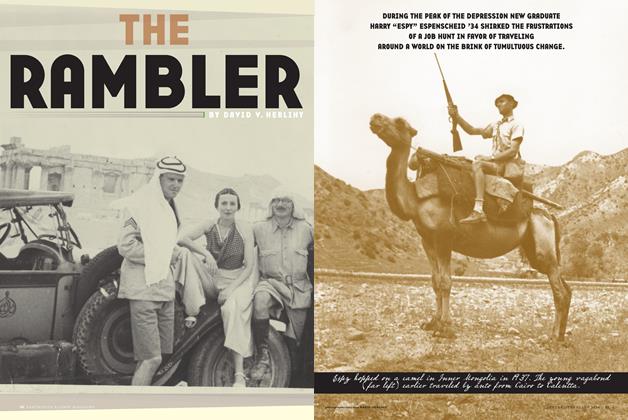

FeatureThe Rambler

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2014 By DAVID V. HERLIHY -

Feature

FeatureA Story: His Grandmother and Vincent

DEC. 1977 By Howard Webber -

Feature

FeatureOn a Freshman Trip, the Destination Is Community

MARCH 1989 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureIt's Where We're Coming From, Citizens

November 1979 By Jeffrey Hart -

Feature

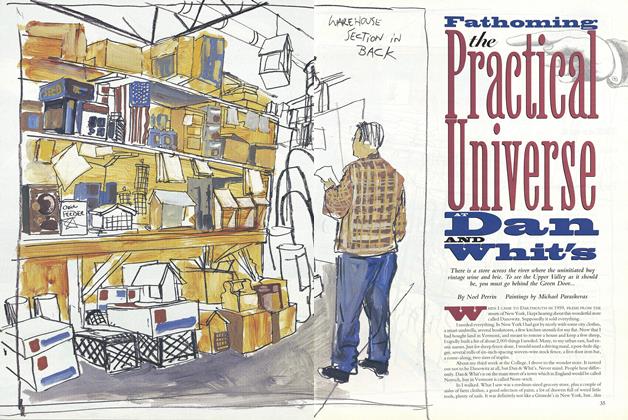

FeatureFathoming the Practical Universe Dan and Whit's

April 1995 By Noel Perrin