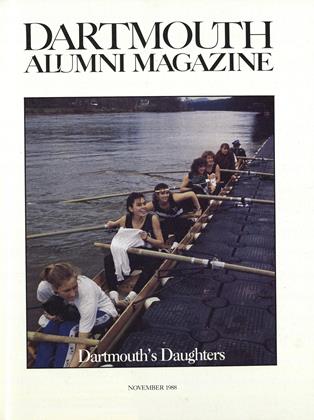

After 16 years of coeducation, women are changing the College; and that causes some institutional discomfort.

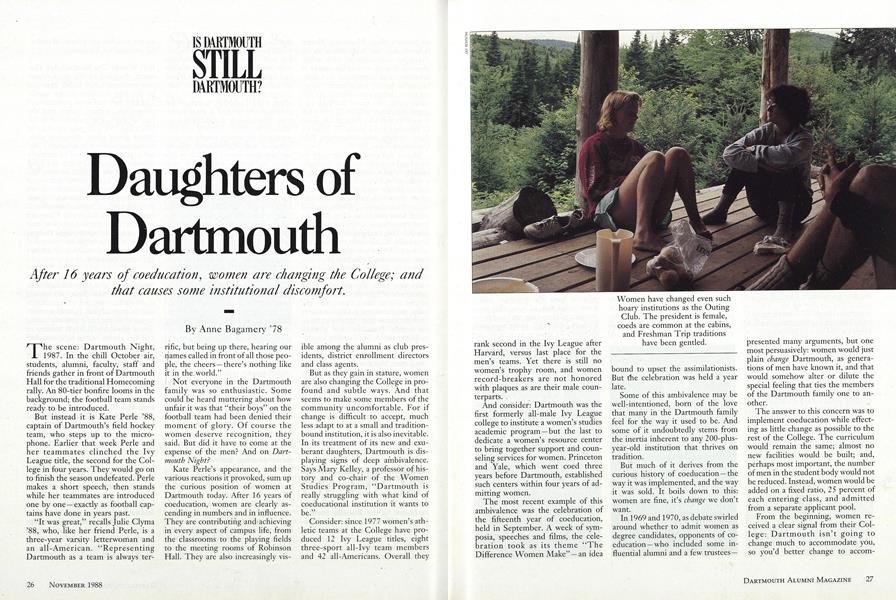

The scene: Dartmouth Night, 1987. In the chill October air, students, alumni, faculty, staff and friends gather in front of Dartmouth Hall for the traditional Homecoming rally. An 80-tier bonfire looms in the background; the football team stands ready to be introduced.

But instead it is Kate Perle '88, captain of Dartmouth's field hockey team, who steps up to the microphone. Earlier that week Perle and her teammates clinched the Ivy League title, the second for the College in four years. They would go on to finish the season undefeated. Perle makes a short speech, then stands while her teammates are introduced one by one exactly as football captains have done in years past.

"It was great," recalls Julie Clyma '88, who, like her friend Perle, is a three-year varsity letterwoman and an all American. "Representing Dartmouth as a team is always terrific, but being up there, hearing our names called in front of all those people, the cheers there's nothing like it in the.world."

Not everyone in the Dartmouth family was so enthusiastic. Some could be heard muttering about how unfair it was that "their boys" on the football team had been denied their moment of glory. Of course the women deserve recognition, they said. But did it have to come at the expense of the men? And on Dartmouth Night?

Kate Perle's appearance, and the various reactions it provoked, sum up the curious position of women at Dartmouth today. After 16 years of coeducation, women are clearly ascending in numbers and in influence. They are contributing and achieving in every aspect of campus life, from the classrooms to the playing fields to the meeting rooms of Robinson Hall. They are also increasingly visible among the alumni as club presidents, district enrollment directors and class agents.

But as they gain in stature, women are also changing the College in profound and subtle ways. And that seems to make some members of the community uncomfortable. For if change is difficult to accept, much less adapt to at a small and traditionbound institution, it is also inevitable. In its treatment of its new and exuberant daughters, Dartmouth is displaying signs of deep ambivalence. Says Mary Kelley, a professor of history and co-chair of the Women Studies Program, "Dartmouth is really struggling with what kind of coeducational institution it wants to be."

Consider: since 1977 women's athletic teams at the College have produced 12 Ivy League titles, eight three-sport all-Ivy team members and 42 all-Americans. Overall they rank second in the Ivy League after Harvard, versus last place for the men's teams. Yet there is still no women's trophy room, and women record-breakers are not honored with plaques as are their male counterparts.

And consider: Dartmouth was the first formerly all-male Ivy League college to institute a women's studies academic program—but the last to dedicate a women's resource center to bring together support and counseling services for women. Princeton and Yale, which went coed three years before Dartmouth, established such centers within four years of admitting women.

The most recent example of this ambivalence was the celebration of the fifteenth year of coeducation, held in September. A week of symposia, speeches and films, the celebration took as its theme "The Difference Women Make"-an idea bound to upset the assimilationists. But the celebration was held a year late.

Some of this ambivalence may be well-intentioned, born of the love that many in the Dartmouth family feel for the way it used to be. And some of it undoubtedly stems from the inertia inherent to any 200 plusyear old institution that thrives on tradition.

But much of it derives from the curious history of coeducation-the way it was implemented, and the way it was sold. It boils down to this: women are fine, it's change we don't want.

In 1969 and 1970, as debate swirled around whether to admit women as degree candidates, opponents of coeducation—who included some influential alumni and a few trusteespresented many arguments, but one most persuasively: women would just plain change Dartmouth, as generations of men have known it, and that would somehow alter or dilute the special feeling that ties the members of the Dartmouth family one to another.

The answer to this concern was to implement coeducation while effecting as little change as possible to the rest of the College. The curriculum would remain the same; almost no new facilities would be built; and, perhaps most important, the number of men in the student body would not be reduced. Instead, women would be added on a fixed ratio, 25 percent of each entering class, and admitted from a separate applicant pool.

From the beginning, women received a clear signal from their College: Dartmouth isn't going to change much to accommodate you, so you'd better change to accommodate Dartmouth. "Fitting in" became the order of the day, as manifested in rituals from learning to chug beer during Freshman Week to singing "Men of Dartmouth" at graduation.

With the numbers of women topping 40 percent, however, an assimilationist message doesn't play as well anymore. Today women and men are questioning everything about the Dartmouth experience, including some of the College's most hallowed traditions. And what they are finding is that many aspects of the "old Dartmouth"-male-educated, rough-and-tumble, and traditionbound-are increasingly out of step with a diverse, coeducational community.

"On my freshman trip I thought they were kidding when they told me the alma mater was called 'Men of Dartmouth'," says Meg Sommerfeld, a junior from Greenvale, New York. "I thought they might mention women later on in the song. When they didn't,I thought, 'Wait what about us?' Loving this place so much, I just felt so left out."

"There are some things about tradition at this place that are just breathtaking," says Lisa Brantsten, an '88 graduate from Palo Alto, California. "But I think traditions should always be questioned because of what they can stand for, which may not be appropriate anymore."

To some extent, the shift in women's attitudes at Dartmouth reflects a shift in the women's movement in general. "In the 1970s, the big thing was equality," explains Nancy Frankenberry, a religion professor and cochair of the Women's Studies Program. "Women were so afraid to call attention to their differences, because we might have made ourselves vulnerable on those very points. Now in the 1980s there's more interest in diversity in the society at large. Women want to say, and feel more comfortable saying, 'We are different take those differences into account.' "

There's no question that, compared to the early years of coeducation, the situation for women on campus has vastly improved. First, consider the numbers. This year's freshman class, the class of 1992, is 44 percent women-the highest percentage in the history of coeducation. The '92s were chosen from an applicant pool in which the number of applications from women was up 13 percent from the previous yearsome indication, at least, that more women are becoming attracted to the College on the Hill. In the aggregate, the 1988-89 student body is 41 percent female.

But women are not simply more numerous on campus; they are also more evident in campus leadership. Take the spring of 1988. The president of the senior class, the president of Casque & Gauntlet Honor Society, the editor-in-chief of The Dartmouth and six of nine senior editors all of these were women. Also on campus that term were the immediate past presidents of the Dartmouth Outing Club and the Interfraternity Council and the general manager of the radio stations again, all women.

Undergraduates weren't the only Dartmouth women taking on leadership roles. Alumnae head the interviewing and enrollment efforts in key districts such as New York and Washington, D.C., and serve as club presidents from Maine to San Francisco. As of June 1988, one of every nine Dartmouth alumni was female a ratio that will increase to one in five by the turn of the century.

Women also have more options on campus than ever before. They can join one of nine sororities or six coed fraternities, live in a coed dorm or in Women's Studies affinity housing. There are two all-female secret senior societies, Cobra and Phoenix, as well as Fire and Skoal and Casque & Gauntlet, which are coed. The Women's Studies Program attracts feminist scholars from around the world, and the Women's Issues League meets every Thursday night to discuss ways to help move the College further along the road to total coeducation.

In the curriculum as a whole, moreover, the contributions of women are being given greater weight. A course on Renaissance literature, for example, includes works by Marguerite de Navarre as well as by Michel de Montaigne. This, argues Mary Kelley, is what a truly coeducational institution should do. And here Dartmouth has made progress. "I used to get questions about why I was including women in my course readings," she says."I don't get those questions anymore."

In short, the days of a token female presence, either on campus or in alumni circles, are clearly gone for good. And the numbers are only going to grow. President James O. Freedman has stated his intention to move Dartmouth's student body to a more equal ratio of women to men. Freedman's statements received powerful backing last spring with the Trustees' resolution to seek "more substantial parity in the number of men and women undergraduates ...

in order to sustain an academic and social environment folly supportive of the educational mission of Dartmouth College."

Most on campus take the Trustees' statement to mean a 50-50 split within the next decade-a move that many favor. "Dartmouth is still too far away from being 50-50," says Russell Stevens '88. "Parity is not the sole answer, but it will make a difference in every area of the campus. Women's voices will become louder in all aspects of Dartmouth, and that will be better for the place when it happens."

Clearly, parity alone is not the answer. In discussions of how to improve the environment for men and women, the fraternity and sorority systems usually come in for a drubbing. Although praised by some for offering support systems for students, particularly amid the transience of the Dartmouth Plan, the single-sex Greek houses have the reputation as the places where sexism flourishes indeed,is de rigueur. "If you're" a man who's at all sensitive to women's issues, it can be hard to make friends with other men in the house," says an 88 fraternity member, clutching a plastic cup of punch at a sorority cocktail party and imploring nonymity. "There's a real tough-guy macho thing in the fraternities. If you don't go along with it, you have to hide it."

Members of the administration, including Dean of the College Edward J.Shanahan, have made it clear that they support a radical change in the Greek system—if not abolition then coaxing all the single-sex houses to become coed. The idea is to eliminate what many see as a major source of sexist thought and behavior. "I think people come here without sexist attitudes and they learn them here," says Mary Turco, acting dean of residential life. "They learn them from their peers who have those attitudes, and they learn them in the Greek system."

A controversial presence on campus ever since coeducation, the fraternities got another black eye in the spring of 1987 when the "newsletters" of two all-male houses were made public. One of the publications contained a cartoon strip about a fraternity man who seduced and abandoned a Dartmouth woman. The woman is depicted as a pig.

The campus was galvanized. "We knew these newsletters existed, and we knew they were bad, but I don't think we knew how bad they were," says Jane Grussing '88, then president of Sigma Kappa sorority. Mary Turco had a talk with the fraternity members who had written the newsletters. She pointed out their offensiveness. "They didn't have a clue," she recalls. " 'This is a joke! A parody!' they said. Either they came in with these weird insensitivities, or they learned them from the system."

The issue peaked last winter when the members of Sigma Kappa pressed charges of sexual harassment against Beta Theta Pi fraternity, after a Beta member performed a stand-up comedy routine that included unprintable references to the Sigma Kappas at a jointly sponsored party. The incident drew attention on campus in part because of Sigma Kappa's reputation as a; solidly traditional sorority house, one not closely identified with feminist causes. But after the newsletters, the Beta incident was the last straw. "Women in the house are just not willing to put up with things that they might have before," says Jane Grassing. The two houses worked out their differences by organizing workshops on sexism.

The sorority system itself, which started in 1977 with one house and has grown to nine, including two for black women, is as controversial as the fraternities. "The sorority system was set up for a good reason-to help women socialize on an equal basis with men-but we've fallen short," says Karen Avenoso '88, former president of the senior class, now a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford. Avenoso joined a sorority her freshman year but depledged in her junior year. "There were two kinds of house meetings: the kind that mirror the fraternity house meetings, with lots of drinking and gossip about what we've done with men, or the kind where women pander to the ideal of the coy, wiley female focusing on dates, formals and marriage.

"There's a lot of pressure to join a sorority, to prove you can fit in at Dartmouth," she continues. "And once you join, there's a lot of pressure to stay in. But I think we can support women in ways that contribute more to the community than another formal party."

Proponents of the sorority system argue that the Greek houses do benefit the community. National sorority rules require that members spend a minimum number of hours on charitable and philanthropic activity, and College rules dictate minimum academic standards for all Greek houses.

Yet the bulk of the houses' activities is unquestionably social. It can even be argued that the sorority system actually fosters greater social dependence on the fraternity system; since all but one of the sororities is prohibited by national rules from serving alcohol, they usually end up cosponsoring parties in fraternity houses, which are allowed to serve alcohol.

The debate over the future of the Greek system is part of a larger question facing Dartmouth and, indeed, society as a whole: is there a place, in a society committed to equality, for exclusive organizations of any kind? "If Dartmouth or society in general were neutral in gender and race, I might buy it," answers Carla Freccero, an assistant professor of French and Italian. "But in a white male institution, these groups need support. That support may take the form of separate associations."

Many also feel that single-sex organizations are a healthier influence if students join them after at least being exposed to coeducational alternatives. One argument for delaying fraternity and sorority rush until sophomore year is that it would give students a chance to form closer relationships with a variety of men and women in their coed dorms, classes and activities before separating into smaller groups.

For many women, however, single-sex organizations still serve an impo rtant purpose: they allow women to get together with those of their own sex. In 1986 Mary Turco interviewed 40 women from the class of 1988 to gain qualitative data on the status of women on campus. Her report, "Daughters of Dartmouth," showed clearly that women felt the need for a separate support system. They found it difficult to form close friendships with other women in a coeducational, male-dominated environment. They cited three main support systems: sororities, women's athletics and the Women's Studies Program.

Of these, athletics is arguably the most mainstream. The women's rugby team is exceptionally tightknit, even throwing its own sororitystyle formals. In some cases the bonding begins before Freshman Week, with early practice. Julie Clyma and Kate Perle were part of a suite of four roommates who met at field hockey practice before Freshman Week. They cemented their friendship through four years of five day a week workouts, plus games.

Ironically, athletics may in one sense be the most completely coeducational aspect of campus life: women athletes say their strongest support comes from male athletes. Even after Dartmouth Night 1987, the football players "never said a word against the fact that we were introduced and they weren't," says Julie Clyma. "They've seen us working just as hard as they do. They know what we're going through. There's tremendous mutual respect."

The strength of any athletic program lies in large part in the coaches. For its women's program Dartmouth has attracted top quality, including the coach of the U.S. national lacrosse team and a former Olympic runner, and has managed to keep them-minimizing the turnover that can devastate recruiting and team morale. But the history of coeducation may have weighted the scales too. "The type of woman that came to this school when it was so overwhelmingly male-they had to be really strong characters to put up with all the grief they took," says Julie Clyma. "That's also the personality that makes a good athlete."

While athletics offers women mutual support through competition, the Women's Studies Program does not begin to seek to emulate the "tough" experiences of the first generations; instead, the program's students and faculty praise it for catering to their special needs. Women who have taken Women's Studies courses tend to become ardent supporters. "The teaching from Women's Studies professors-even in non-Women's Studies courses-is better than in any other courses," says Carolyn Foley '88. "They really encourage participation, and they're passionately interested in what they're teaching."

Perhaps the most far reaching contribution of the Women's Studies Program is the higher profile it has given to issues of race and gender issues that were discussed only occasionally in the early years. Teachins, speak-outs and symposia spill over into student discussions.

Students say that they react to all this self-examination either by becoming more sensitive to issues of gender and race ...or by tuning out altogether. "After four years here, I'll wince if I hear a woman referred to as a girl," says Russell Stevens. "It's not because I'm the most liberal person but because I've had it drummed into me for four years."

"I think a lot of men and women enter here ready to discuss issues, and they become more closed-minded because they get tired of all the discussion," says Kim Chaplin '88, a student member of the Women's Support Task Force that drafted the recommendation for a women's resource center. "You try to tell them, 'What are you going to do out in the real world, where you may be discriminated against or passed over for promotion or hit on because you're a woman?' They usually answer, 'I'll deal with it then.' "

"Consciousness-raising can makeparticipants uncomfortable," saysCarla Freccero, who is one of the most outspoken advocates of women's issues on campus. "I've had women students come to me and say, 'I took a Women's Studies course and now I'm a malcontent; I'm much more sensitive.'I don't think that's necessarily bad as long as you do something to make it better."

What many agree will make it better is a greater sense that men and women at Dartmouth are not rivals but partners entitled to fall membership in the College. Turco's "Daughters" study ends on an upbeat note: "Dartmouth has the talent, resources and professed commitment to enter the twenty-first century as the premiere academic, coeducational institution in the United States. This will happen if all of the sons and daughters of Dartmouth perceive themselves, in all aspects of College culture and ecology, to be equal members of one family."

Women have changed even such hoary institutions as the Outing Club.The president is female, coeds are common at the cabins, and Freshman Trip traditions have been gentled.

The first women were added to the College in a fixed ratio 25 percent of each entering class.

Kathryn Lea Sewell '77 M.D. from Duke. Instructor in Department of Internal Medicine at Harvard's Beth Israel Hospital, specializing in rheumatology and geriatrics.

Edith B.Ullman '77 Holds a law degree from Berkeley. Fire apparatus engineer, California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection.

Elizabeth A. Fairbanks '78 Staff member, Resource Center for Nonviolence, Santa Cruz, California.

Athletics is a chief way that Dartmouth women say they find psychological support.

Pauline J. Cole '76 Has worked as a system programmer for the Dartmouth Time Sharing System and as a school teacher. With help from friends and family, built her own house in Thetford Center, Vermont. Now stays at home with her newborn son.

Catherine E. Wilson '75 Native American, Nez Perce tribe. Law degree from Arizona State. Tribal attorney for the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, Pendleton, Oregon.

Jennifer Leigh Warren '77 Actress and singer. In original cast of "Little Shop of Horrors." Played the title role in "Abyssinia," a gospel musical in New York. Debuted on Broadway as a slave in "Big River." Has appeared in television's "All My Children" and in network commercials.

Heather Mayfield Kelly '78 MBA from Hazard, worked at the Bank of Boston, Author of the book, What They Really TeachYou at the Harvard BusinessSchool.

How will women affect Dartmouth's future? One fifth of the alumni will be female by the turn of the century.

"As a woman, you weresomething that thealumni were struggling todeal with."

"Maybe being one of the first women prepared me for the challenge of being one of the first women in firefighting."

Time Line September, 1953: Botanist Hannah Croasdale becomes first woman to be granted faculty status. September, 1969: Seventy female exchange students come to campus for one year. November 21, 1971: Trustees vote to admit women as degree candidates and to begin year round operation. June, 1972: Dartmouth graduates last all-male senior class. September 22, 1972: Susan Corderman of St. Louis, Mo., becomes first woman to matriculate. Male to female ratio is nine to one. January, 1978: Sigma Kappa becomes; first officially recognized sorority. September, 1978: Women's Studies Program established. April 24, 1979: Trustees vote to admit male and female students on an equal basis. April, 1980: Hallidie Grant becomes first female president of a senior class. January, 1981: Mary Cleary '79 becomes Dartmouth's first female Rhodes Scholar. June, 1982: Ann Fritz Hackett '76 elected first alumna trustee. May, 1988: Lyrics of alma mater officially changed to make it non-sexist. September, 1988: Class of 1992 comprises 44 percent women — highest proportion of females in Dartmouth history. September 24, 1988: Women's Resource Center inaugurated.

"I took full advantage ofthe 'D' Plan. In a verycondensed time, I got asolid grounding for myongoing commitment tononviolence and socialchange."

"When I went, peoplewere more tolerant of diversity."

"From the beginning,, women received a clearsignal: Dartmouth isn't going to change muchto accommodate you, so you d better change toaccommodate Dartmouth. Fitting in becamethe order of the day, as manifested in ritualsfrom chugging beer during Freshman Week tosinging 'Men of Dartmouth' at graduation."

Remembering the Beginning Last September, in five days of "have moved us closer to genuine ates a pressure to study the lives events ranging from the for- coeducation," she said. of women as well as the lives of mal opening of the Women's Re- Several of Dartmouth's "pi- men." Such pressure has been source Center to a one-act play, oneer" alumnae returned to par- manifested in the nationwide Dartmouth set the evolution of its ticipate in the week's events, growth of women's studies (from women in the context of society at offering a personal account of 20 to 30,000 courses since 1969), large. "Coeducation: The Differ- early coeducation. They described which Freedman called "a very ence Women Make" was the title the isolation they felt as a small significant liberating event in in of a conference that cOmmemo- minority and recalled that some tellectual terms." rated a decade and a half of women men resented their presence as an One session brought together at Dartmouth College. intrusion, "I didn't consider my- some of the feminist movement's Coeducation was instituted at self to be a feminist," said one leading activists and scholars, in the College primarily in response woman, "but I was angry that we eluding Ms. Magazine founder to changes taking place outside. had to justify why we were here." Gloria Steinem and Angela Davis, recalled former President John G. The condition of women at the who once ran for vice president on Kemeny. "With women playing College evolved as the ratio of fe- the Communist Party ticket. The increasingly important roles in a males to males became more eq- effort to include diverse factions changing world," he said, "the old uitable. Still, Wheaton College was a crucial development in the argument for an all-male institu- President Alice: Emerson cau- . movement's strategy, according to tion had become obsolete." tioned that "access does not pro- Steinem. Davis stressed the importance The 1971 decision to admit duce equality," citing the paucity of building a "multicultural" women, momentous though it of tenured women in higher ed- feminist movement, was, did not constitute a single, ucation that persists despite a na- "Our differences should not be distinct change, explained History tional parity in numbers of male seen as problems but rather as the Professor Mary Kelley. Subse- and female students. source of richness and strength," quent events such as the establish- Dartmouth President James O. declared activist Charlotte Bunch, ment of the Women Studies Freedman conceded that the hum- "and the integration of our difference Program, the move to sex-blind ber of women on the faculty "is can mean the broadest possibility admission, and the recent opening still too small," but he asserted for our survival as a of the Women's Resource Center that "the presence of women ere- planet." —Elizabeth M. Klein '88

"At Dartmouth and at business school, the women who are hanging in there and making it are stronger than the men."

Anne Bagamery '78 is a freelance writer living in London. She has been a staffer with Forbes Magazine and speechwriter to the president of Pcific Bell.A former Whitney Cambell Intern with the Alumni Magazine and the first woman editor-in-chief of The Dartmouth, Bagamery revisited the campus during last spring and summer.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureGlory Days

November 1988 By Woody Klein '51 -

Feature

FeatureThe Helplessness of a "Bureaucrat of Legendary Proportions"

November 1988 By Jonathan Cowan '87 -

Feature

FeatureQuestion: What Professional School Gives Credit for Throwing Pies?

November 1988 By Steve Lough '87 -

Feature

FeatureGetting Gored by a Rhinoceros Was Only Half the Experience

November 1988 By Emily Hill '90 -

Sports

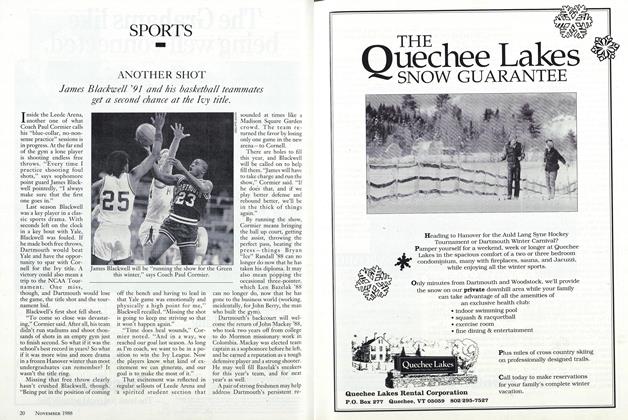

SportsANOTHER SHOT

November 1988 -

Article

ArticleSHOULD DARTMOUTH DIVEST?

November 1988

Anne Bagamery '78

Features

-

Feature

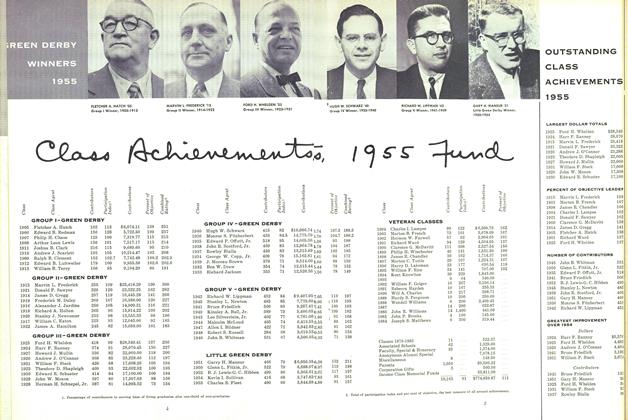

FeatureChass Achierement 1955 Fund

December 1955 -

Feature

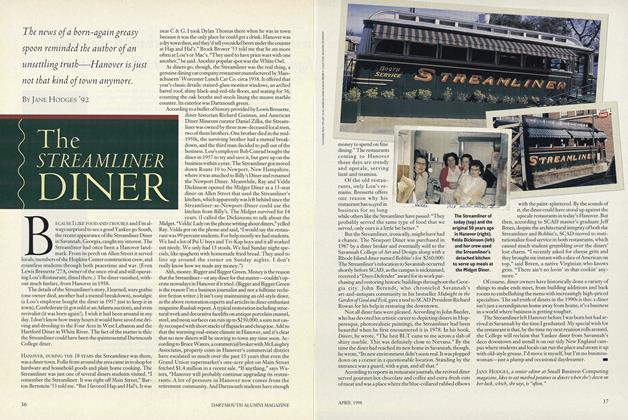

FeatureThe STREAMLINER DINER

APRIL 1998 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Feature

FeatureJourney's End: The Assyrian Reliefs at Dartmouth

SEPTEMBER 1985 By Judith Lerner -

Feature

FeatureThe Best of The Old Farmer's Almanac

June 1992 By Judson Hale '55 -

Feature

FeatureIt’s the Ideas, Stupid

April 2000 By KEITH H. HAMMONDS ’81