COMPUTER MAIL RETURNS US TO A GRACEFUL TIME WHEN MESSAGES WERE DELIVERED BY SERVANTS.

IF YOU WORK FOR A SIZABLE organization, you may be one of the several million Americans who use electronic mail, or messages sent by computer, and you see its civilizing potential.

Or maybe you don't. You may be one of those who find disembodied telephone conversations more "human," somehow. I couldn't disagree more. There is something charmingly Victorian about exchanging notes from a distance, like calling cards left on silver trays. When Margaret Fuller stayed at the home of her friend Ralph Waldo Emerson, the two philosopher-poets would communicate by means of notes passed by servants from floor to floor. Very like "e-mail."

Few places have realized the technology's quaint charms as has Dartmouth, with its six miles of underground coaxial cables and its software ingenuity. The College's 8,000 Macintosh computers have reached that computer Nirvana called "connectivity," the state of being how positively Silicon Valleyish! connected. Dartmouth's e-mail system, called "Blitz Mail" by its campus inventors, allows users to send messages and whole documents with the click of a mouse. The system has led to a new verb in the Hanover lexicon: to blitz, as in, "I'll blitz you that lecture when I get to the office."

The name sounds rather coarse, but oh, the effect is not. A little beep is all that alerts you to a message. No heart-seizing bell, no searching secretary, no telephone tag, no infestation of pink slips. You answer at your leisure, when your thoughts are properly collected.

Granted, Blitz Mail precludes scented stationery, furious pen strokes, wax seals, fancy signatures, and little cartoon doodles. As its developers in the Kiewit Computation Center like to put it, the system "reduces communications to the lowest common denominator in terms of text presentation." Kiewit, which clearly is concerned about the human side of computing, wants to infuse body language into what it calls "the evolving e-mail culture." Its newsletter, Interface, has developed some symbols to stand in for the human face. To comprehend them, simply tilt your head sideways and see your correspondent

wink ;-) or look shocked :-o or wear hornrimmed glasses B-) or scream or even smoke :-Q

Kiewit is on to something. It is adding humanity not just to computing but to the very workplace. One imagines young Tuck students, business inamorata, sending each other love memos through the ether and indulging in what Milton might have called "mutual and partaken blitz." These are visionaries, these Kiewit people. They began burying cable beneath Dartmouth more than 20 years ago, foreseeing a connected campus half a decade before the personal computer was invented.

But even they are mortal. They could not have imagined that Blitz Mail would change the way people work. Professors blitz students in their class, "enclosing" syllabi. Campus environmentalists blitz a paperless, electronic magazine, "Sense of Place," to some 800 computers around the College. Administrators blitz colleagues around the world through international e-mail networks. This popularity of Blitz Mail's has almost choked it at times. More than 5,200 different users signed onto the system during a typical week last April, sending 58,728 messages (not counting notes sent to multiple recipients). During normal working hours a message is sent every four seconds. The mainframe computer that handles this cataract of mail occasionally gets overwhelmed during peak hours, slowing delivery and turning communication into a conversational version of postal chess with long, meaningful pauses. But then, we all have had conversations like that, even without computers.

Here at the Alumni Magazine, the system's advantages have changed our lives. We used to schlepp manuscripts around the office, interrupting each other with shouted questions like, "Does 'schlepp' have two p's?" and spending frustrating hours on the telephone trying to hunt down faculty members. Now we blitz, and the office has assumed a more contemplative air. On weekends and evenings we can work at home, blitzing messages and documents over telephone wires. Our art director, J Porter, blitzes us electronic layouts from his home an hour away. Even story research goes more smoothly; the "interviews" for this article were conducted entirely by blitz.

By allowing us to communicate ethereally, e-mail has already brought us closer to the long-sought paperless office; now it lets us imagine the officeless office, where a staff could collaborate in a wholly electronic meeting place of the mind. And if we pined for human contact? We would meet in a restaurant, in a park, in a canoe, by an editor's hearth, anywhere but in some cramped, white-walled, gossipfilled space. Then we'd be talking humanity, ma

Jay Heinrichs is editor of this magazine.His e-mail address is jay.heinrichs@dart-mouth.edu.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

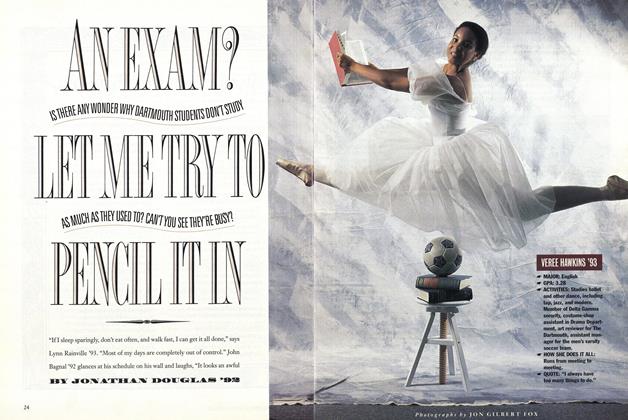

FeatureAN EXAM? LET ME TRY TO PENCIL IT IN

September 1991 By JONATHAN DOUGLAS '82 -

Feature

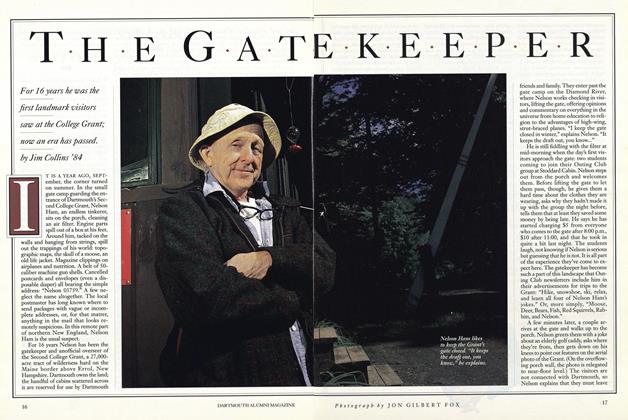

FeatureThe Gate keeper

September 1991 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

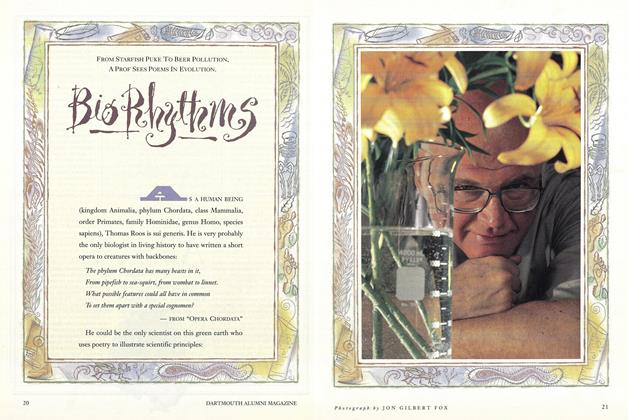

FeatureBio Rhythms

September 1991 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

September 1991 By E. Wheelock -

Article

ArticleAFTER THE WALL

September 1991 By Professor Konrad Kenkel -

Class Notes

Class Notes1975

September 1991 By W. Blake Winchell

JAY HEINRICHS

-

Feature

FeatureIS DARTMOUTH STILL DARTMOUTH?

SEPTEMBER 1988 By Jay Heinrichs -

Cover Story

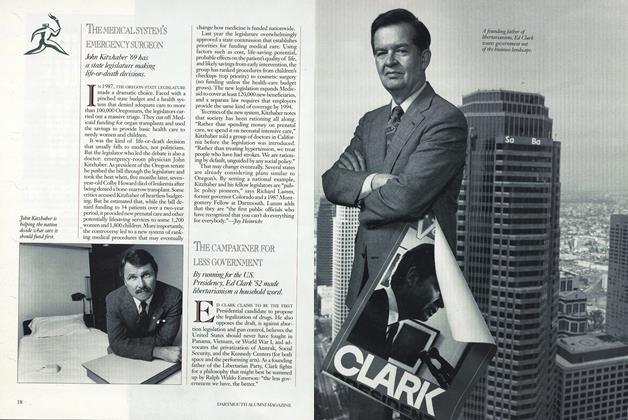

Cover StoryTHE MEDICAL SYSTEM’S EMERGENCY SURGEON

JUNE 1990 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleENGINEERING THE FUTURE

FEBRUARY 1991 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleBeyond Scrapbook

May 1994 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleStatement of Ownership, Management and Circulation (Required by 39 U.S.C. 3685).

OCTOBER 1994 By JAY HEINRICHS -

Cover Story

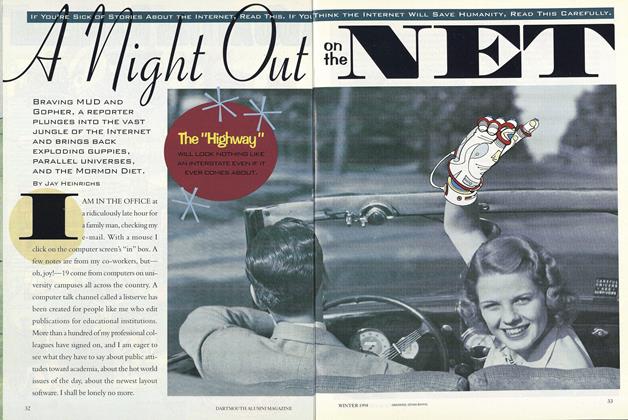

Cover StoryA Night Out on the Net

December 1994 By Jay Heinrichs

Features

-

Feature

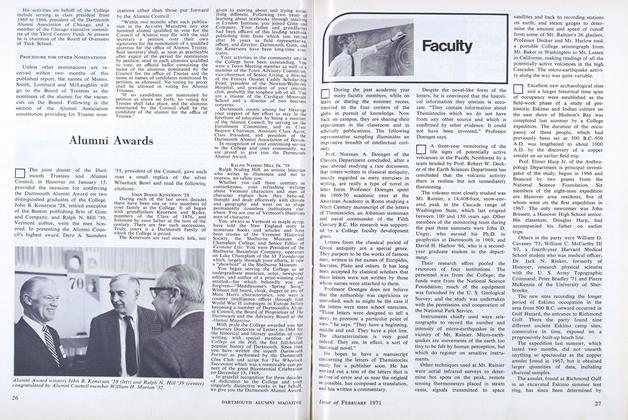

FeatureAlumni Awards

FEBRUARY 1971 -

Feature

FeatureOnce Upon a Time

December 1980 -

Feature

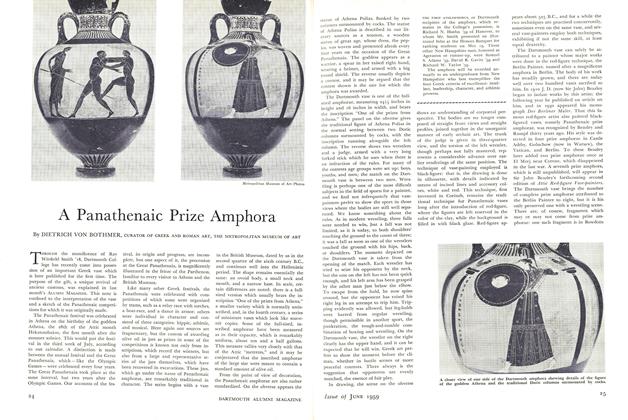

FeatureA Panathenaic Prize Amphora

JUNE 1959 By DIETRICH VON BOTHMER -

Feature

FeatureIn the Crossfire

MAY | JUNE 2016 By FAY WELLS, TU’06 -

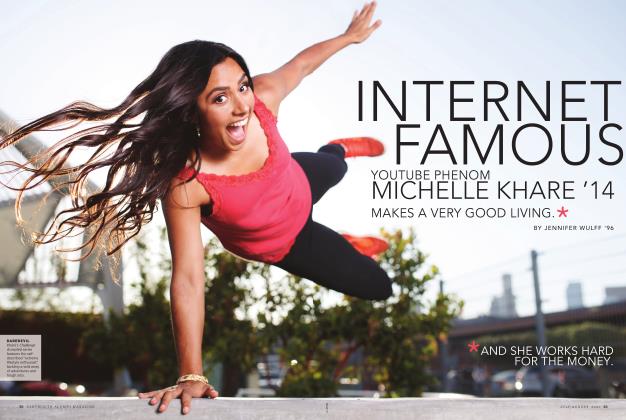

Cover Story

Cover StoryInternet Famous

JULY | AUGUST 2020 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

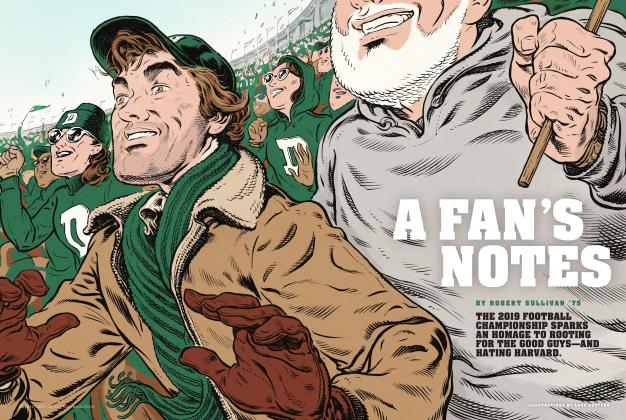

FEATURE

FEATUREA Fan’s Notes

MARCH | APRIL 2020 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75