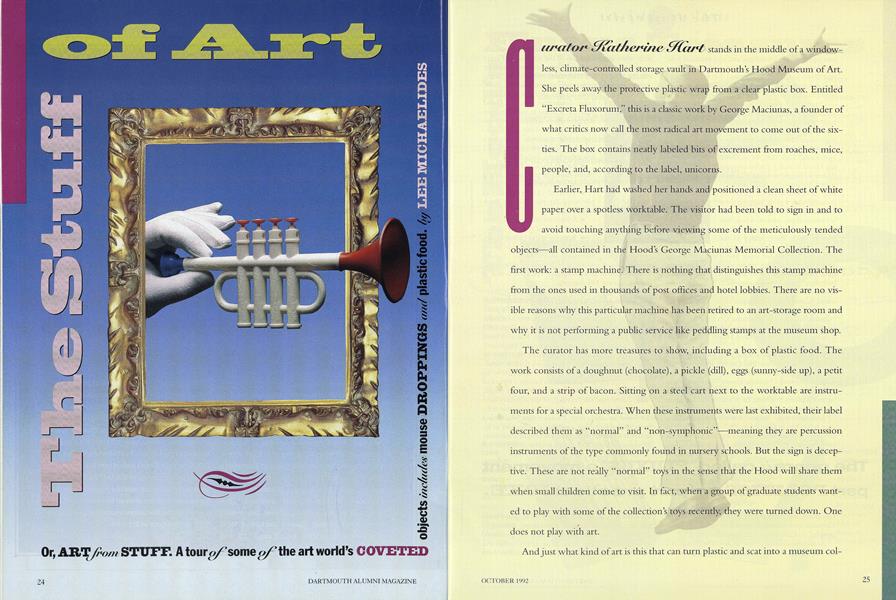

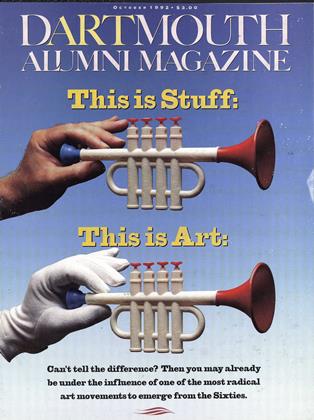

Or, ART from STUFF. A tour of some the art world's COVETED

objects includes mouse DROPPINGS and plastic food.

wator Bathering Aart stands in the middle of a windowless, climate-controlled storage vault in Dartmouth's Hood Museum of Art. She peels away the protective plastic wrap from a clear plastic box. Entitled "Excreta Fluxorum," this is a classic work by George Maciunas, a founder of what critics now call the most radical art movement to come out of the sixties. The box contains neatly labeled bits of excrement from roaches, mice, people, and, according to the label, unicorns.

Earlier, Hart had washed her hands and positioned a clean sheet of white paper over a spotless worktable. The visitor had been told to sign in and to avoid touching anything before viewing some of the meticulously tended objects—all contained in the Hood's George Maciunas Memorial Collection. The first work: a stamp machine. There is nothing that distinguishes this stamp machine from the ones used in thousands of post offices and hotel lobbies. There are no visible reasons why this particular machine has been retired to an art-storage room and why it is not performing a public service like peddling stamps at the museum shop.

The curator has more treasures to show, including a box of plastic food. The work consists of a doughnut (chocolate), a pickle (dill), eggs (sunny-side up), a petit four, and a strip of bacon. Sitting on a steel cart next to the worktable are instruments for a special orchestra. When these instruments were last exhibited, their label described them as "normal" and "non-symphonic"—meaning they are percussion instruments of the type commonly found in nursery schools. But the sign is deceptive. These are not really "normal" toys in the sense that the Hood will share them when small children come to visit. In fact, when a group of graduate students wanted to play with some of the collections toys recently, they were turned down. One does not play with art.

And just what kind of art is this that can turn plastic and scat into a museum collection? The genre is called "Fluxus," a movement part politics, part surrealism, and part practical joke that helped launch the kinds of performance art that drives Jesse Helms crazy and that itself continues to challenge, taunt, and demystify the art world's status quo.

One of the movement's most interesting (and perhaps annoying) traits, at least from the perspective of a museum whose primary purpose is the acquisition and preservation of objects, is that Fluxus art tends to be ephemeral. Last May, for instance, the Hood hosted a Fluxus concert. About 40 people watched as a wildhaired, pajama-clad man "demystified" a Hood Museum gallery by dancing with a gong hanging from his neck. Performing with him was a serious-looking woman whose hair was cropped close to her skull,

Marine style. Each sound of the gong caused a slow, deliberate movement of a limb or her torso. She stared unblinking straight at the audience, whose reaction ranged from quiet appreciation, inner tranquillity (or perhaps boredom; a few people appeared to be asleep),.restlessness (a toddler inadvertently summoned security forces by setting off the burglar alarm), and hostility (one faculty member later described the show as "unmusical" and "an embarrassment"). Conventional performers might have considered the show a disaster, but in the world of Fluxus the reactions Constituted a success.

If you still don't understand what Fluxus is, don't feel badly. Neither does Phil Corner, the man in thewhite pajamas. When asked to define the movement, he replied: "Nobody knows"; If anybody ean make that statement, Corner can. Besid.es being a retired Rutgers professor, he is one of the foundingmembers of the Fluxus collective. His composition"Piano .Activities" became a seminal Fluxus work after it was first performed in 1962. The highlight of the piece was the demolition of a grand piano. That performance at the first Fluxfestival in Wiesbaden, Germany, was captured by a television crew. The Germans took a liking to what they called the "Flux people," and the movement took off.

Academicians have come to describe Fluxus as a subversive movement with a mission to upend the established ideas of art, artists, and museums. As with other art movements of the sixties, the Fluxus artists were motivated by a desire to throw a spanner into the works of the traditional art paradigm. Some skeptics might consider their success a failing. Now, three decades after the Wiesbaden piano deconstruction, the Hood Museum is home to such treasures as a prestigious collection of New England silver and the 2,900-year-old Assyrian reliefs, along with fake fruit, toy instruments, and a few other gems, including:

An old black and white television tuned to produce a single line across the screen.

Half of the original paper score for the "Young Penis Symphony."

A machine that, inserted into the mouth, makes the user smile.

A music stand called ''Telepathic Music No. 2." (not to be confuted with "Telepathic Music No. 1," a more ambitious work consisting of 20 music stands).

Ephemera advertising such Flxus activities as Festivals, shows,,,and concerts.

he discriminating reader may at this point ask: Is this some kind of a joke? Well, in a way it is. Fluxmaster Maciunas said in an interview before his death in 1978 I that he was pleased Fluxus had not been added to museum collections, "High art," he observed, "is something you find in museums. Fluxus you don't find in museums...because we've never intended to be high art. We came out to be like a bunch of jokers," So who is having the last laugh, now that the leavings of these jokers have become ensconced in museums? It is an ironic tribute—and so very, very Fluxus that Maciunas's friends would establish a memorial collection in his honor at a conservative, elite, Ivy League institution. Maciunas, a New York-based graphic designer, was not a total anarchist. He at first tried to give Fluxus a definition in the form of a manifesto. Among its provisions was that works would be produced anonymously in the name of an artists' collective and that they would be inexpensive. Maciunas went so far as to devise a distribution system that included a chain of "Fluxshops" and a mail-order business. (They were anything but profitable; a Fluxshop that Maciunas ran in New York went an entire year without selling a single item. Another Fluxshop simply bartered art for any object on a pound-tor-pound basis.) The manifesto included a passage that read, "Flux-Art-Nonart-Amusement... strives for the monostructural, non theatrical, non baroque, impersonal qualities of a simple natural event, an object, a puzzle, a gag. It is a tusion of Spike Jones, Dada, Games, Vaudeville.. Cage and Duchamp."

None of the Fluxus artists ever signed the manifesto. And that says as much about the dynamics of the individuals as it does about the personality of the founder. In death, Maciunas, with his legacy of zany projects, outlandish costumes (his gorilla suit was familiar among his friends), and eccentric eating habits (at one point he declared that the ideal diet consisted of canned fish; he purchased a full year's supply and washed it down with, vodka), has caused some people to turn him into a paper crown pope. But that isn't the case. Ken Friedman, a Fluxus artist, describes Maciunas as "an exasperating genius"—a man with a chess player's mind. Friedman adds, in a statement startling for being about the. would-be founder of a movement, "George could not-haye.gotten anyone to follow him." In the early days of Fluxus, Maciunas demanded (unsuccessfully) that the artists assign all rights to their work to the movement's cooperative, even though he lacked the resources to publish and distribute the art. Maciunas's critics and friends alike concede

that the man's personality was more than compensated by his brilliance. ''What is central to Fluxus are the ideas," maintains Owen Smith, a professor of art history at the University of Maine. Smith is the author of a doctoral dissertation whose title is "George Maciunas: A History of Fluxus, or the Art Movement that Never Existed." Just what did existwhat Fluxus actually wasis still being debated. In 1982 Dick Higgins, a poet, artist, composer and Fluxus co-founder, wrote an essay outlining nine criteria—internationalism, experimentalism, intermedia, gags, and the like that would officially determine whether a work was truly Fluxus. Higgins's thoughts were later expanded by Ken Friedman, who came up with 12 criteria, But such theoretical punctilios pale next to a Fluxus trait at once endearing and maddening: the membership never could agree on what constituted a member. One reason for this chaos among the nomenklatura is that Fluxus, as a movement, was named by the actual, practitioners. One artist has noted that "change was-built into the; name-';' Unlike-such genres as Pop Art, Modernism, and the Hudson River School, whose Jabeis sprang from the pens of art critics. Fluxus had the freedom to go its own way. George Maciunas did try to impose some standards on the-group. But, being ever-loyal to the movement's anarchical cause, they ignored him.

Maciunas didn't live to see Fluxus institutionalized by such prestigious institutions as the Santa Monida—based Getty Center for the History of Art arid the Humanities, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, or the Tate Gallery in London. But if he is rolling:in his grave, it likely isn't from distress. For one thing, he might be delighted by what Fluxus ddes to standard museum procedures. Curators, on the other hand, are not quite so tickled. Museums are supposed to preserve their holding in perpetuity. Some Fluxus works were specifically designed to self-destruct.

"The purpose of Fluxus is to perish, change, and to be converted," explains Getty curator Marsha Reed. Thanks to Maciunas and company, the Hood must cope with a leaking honey pot, a jar of putrid grease (both by Joseph Beuys), and a decomposing mess by Claes Oldenburg titled "Abandoned Prototype of Soft Ketchup Bottle." Over at the Getty, Reed's problems are even worse. That, staff is trying to "stabilize" the body of a Fluxmouse. The dead rodent, sealed in ajar of formaldehyde, is breaking apart. And then there is the problem with the food. Unlike the Hood, which except for the honey has only plastic menus, the Getty owns Fluxus objects made of real food, which is doing exactly what mere, nonartistic food does: it is rotting.

Another problem facing museums with Fluxus collections is how to account for the stuff. Although the Maciunas collection has been at Dartmouth for some 14 years, it has never been fully catalogued. The truth is, the people at the Hood don't know how to, exactly. Nor does any other museum. "You don't get a chance to catalog mouse turds in a fine-art

museum very often," notes Kellen Haak, registrar at the Hood. The Hood is in the process of writing a grant proposal seeking funds to catalog the collection. Along the way they hope to establish some protocols for the classification of such anti-art.

The patient reader, noting the movement's ephemeral nature, may have thought by now of another good question: Why not hold a big Fluxus yard sale, invite the Getty, and use the proceeds to buy something that won't attract ants?

The experts at Dartmouth reply that Fluxus offers a rich field for academic study. One reason is that Fluxus was built on an important artistic tradition most notably the French-born Dadaist Marcel Duchamp's affinity for scatological humor and his pioneering use of ready-made items. (Duchamp, if you recall your art-history class, promoted the artistic qualities of urinals.) Several of the original Fluxus artists were pupils of composer John Cage. Concepts introduced by Cage were later incorporated into Fluxus, and Cage himself worked on various Fluxus projects. Fluxus artists became pioneers at uniting the visual and performing arts, a breakthrough that has given way to what is now known as performance art. In short, Fluxus represents a link between the art movements of the early part of the century—surrealism, Dadaism, and the like—and today's post-modern culture. "Fluxus early on took on a role of exploring the meaning of performance and demystification of stage and gallery," says Larry Polansky, a Dartmouth music professor. While the academic community is only now starting to evaluate Fluxus, Polansky believes there is a richness to the movement that belies the simplicity of the artifacts.

Fluxus artists were often ahead of their peers in experimenting with new ideas; execution wasn't exactly a priority. But when these artists made videos, smashed pianos, or took off their clothes, they were preparing the way for the generation of artists that is currently causing heartburn to the National Endowment of Arts. Those Fluxus explorations have influenced a whole generation of performance artists, according to Colleen Jennings-Roggensack, former director of programs at the Hopkins Center and now executive director for public events at Arizona State University. Roggensack rattles off a long list of names that includes Karen F.inley (the

female performance artist who endeared herself to Senator Helms by covering her nude body with chocolate), Holly Hughes, Tim Miller, Tricia Brown, Yvonne Rainer, and the stone-faced dancers called the Blue Men. "Fluxus," says Roggensack, showed "how to do what had not been done." Maine's Owen Smith argues that Fluxus's conceptual legacy can be found in such varied artists as the German Neo-Expressionists, painters like Eric Fischl (who had an exhibit at the Hood last year), and performer, musician, and filmmaker Laurie Anderson.

Another reason Fluxus interests scholars is the celebrity factor. Although founder Maciunas advocated cated objects of little value that were produced anonymously, Fluxus artists like Joseph Beuys, Nam June Paik, and Yoko Ono have become famous on their own. Fluxus projects also attracted the participation of other big names such as John Cage, John Lennon, and Christo. (In 1970 Maciunas invited the public to impersonate John and Yoko at a gallery opening.) The star factor, plus a major outbreak of Sixties nostalgia, has had another effect on Fluxus: the stuff has become pricey. Jan van der Marck, the director of Dartmouth's museum and galleries from 1974 to 1980, was a Fluxus fan from the beginning. He sees the end of the eighties and the collapse of the art market as two more reasons Fluxus is drawing ing attention. Van der Marck, who is now chief curator at the Detroit Institute of the Arts, predicts that "the nineties will be favorable to Fluxus as people rethink the overblown, offensive, extravagant concept of art that was held during the eighties. Fluxus was never done for money and hence is somewhat untainted."

Fluxus likely won't remain untainted for long, however. This is the 30th anniversary of the movement. Once the mainstream press and art journals' start reporting; on Fluxus retrospectives being staged at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the University of lowa, the Franklin Furnace, the Walker Art Center, and Chicago's Museum .of Contemporary Art, prices are bound: to increase, The first Fluxus Yearbox, which originally sold for $20, was advertised recently by a New York Gallery tor $15,000. Van der Marck predicts higher prices still. "Now is the time to look and make decisions," he tells potential buyers. "Although Fluxus-was once in the ditne-a-dozen-ca'tegbfy, there isn't a lot of material. Now is the time to buy."

Hood Director Timothy Rub is not unaware of the ironic aspects of Fluxus. Amid the art books in his office sits a cardboard cube with a picture of George Maciunas on it. Rub smiles and says, in good curatorial understatement, "It is an oxymoron to have a Fluxus collection." Rub believes that the objects in the Maciunas collection are not important so much as objects as for what they represent. Cataloguing Fluxus is like cataloguing an ethnographic collection. When a painting is catalogued, a brief description is usualy sufficient; the painting itself is a communication device. Fluxus is different. Recapping a menu of fake food isn't very helpful, and the fake food doesn't say much on its own. For scholars to make sense of Fluxus, the cataloguer has to establish the intent of the artist and then place the work in a cultural and historical context. In the meantime, time, Rub figures that it will take several people a few years to catalog the Hood's collection. They won't be working entirely in the dark. While the Fluxus people may have had disdain for art objects, they had a passion for self-documentation. Although their art might be a joke, the artists took themselves quite seriously, carefully preserving their letters, plans, and notebooks, Maciunas's dreams for Fluxus included the rehab of loft space in New York's, Soho district and the purchase of a tropical island for a Fluxus retreat. (According to the fluxus Codex, a reference work by Jon Hendricks, the Soho plans' caused a run-in with New York authorities over building-code violations. A plan to buy Ginger Island in stymied because "everyone slept naked under a tree that exuded a poisonous sap, causing rashes and fever," according to Hendricks.) One particular Maciunas obsession was a series of elaborate flow charts that placed Fluxus in the context of world art history and detailed the various exploits of the Fluxus artists. This documenta- tion may or may not be of use to curators. If a particular artist displeased Maciunas, he would strike the victim from the chart. Being excommunicated in this way didn't mean much, however. By most accounts the artists paid no more attention to Maciunas's charts than they did to his rules.

Still, Fluxus historians have plenty of useful material. In addition to countless handbills, posters, and photographs produced for countless Fluxfestivals, the group also published its own newspapers. Maciunas's original plan, in fact, was to start a magazine called, naturally, Fluxus. Phil Corner's piano piece, performed by Maciunas, was supposed to draw attention to the magazine—which never actually produced an issue. Later, when contributions to the proposed publication became too weird to print, Maciunas hit upon the idea of Fluxus "yearboxes" like the one that now costs $15,000. These annual editions—packed in boxes instead of bound—usually contained scores, objects, prints, and photographs. (Within a production run these individual yearboxes rarely contained exactly the same contents—another Fluxus trait that drives museum curators crazy.) Still another curatorial plus: many of the artists who created the works are still alive. The Hood's Timothy Rub is in regular contact with people in the Fluxus community, including Ken Friedman, who has made numerous donations of Fluxus work.

Despite the growing interest in Fluxus, Dartmouth's collection has maintained a low profile from the start. Van der Marck, a personal friend of many of the Fluxus artists, established the Maciunas memorial at the College by donating works from his personal collection and soliciting gifts from Fluxus artists. In 1979 he organized a Fluxus festival and exhibition for Hanover. The reaction from the Dartmouth community? "T-H-U-D," says van der Marck cheerfully. "The reaction fell like a proverbial brick." Neither van der Marck nor the artists were offended, however. They were used to such a nonreaction. In the intervening years, use of the collection has ebbed and flowed with the whims of museum directors. Some simply ignored it. Former Hood Director Jacqueline Baas expanded the collection; and now Rub has plans for it.

Rub admits to having grown fond of the collection since becoming director. He says he wants to encourage more events like the Phil Corner concert, because they "expand on the concept of what a teaching museum is supposed to do." Rub would like to see more of that kind of collaboration between the museum and academic departments in the future. On the other hand, he is reluctant to follow the example of the University of lowa, which opened last month at the Franklin Furnace a major retrospective entitled "Fluxus: A Conceptual Country." Rub feels that such a large exhibit is incapable of capturing the movement's small-scale, spontaneous spirit. Instead, as the Hood gears up to celebrate its tenth anniversary, he wants a series of small, highly focused Fluxus exhibits that demonstrate individual facets of this seemingly simple but highly complex art phenomenon. Over the next few years don't be surprised if the Hood explores the poetry of Fluxus, exhibits "Fluxus multiples" (works de-signed for the mass 'market), or compares and contrasts Fluxus and Minimalism. In the meantime, Rub reports that the Maciunas Collection continues to grow, in part because Fluxus is still being produced: the movement is still very much alive.

Then again, maybe not. Typically, the movement is split among aficionados who debate its continuing existence. Some critics, and even some artists, say Fluxus ended when Maciunas died in 1978. (The 606-page Fluxus Codex ends at that year.) Others note happily that the Fluxus manifesto drafted by Maciunas was never signed. Therefore, they say, Fluxus has every right to continue. One artist claims that Fluxus hasn't happened yet, while another says simply that "Fluxus has fluxed." For the record, Maciunas believed that the golden age of Fluxus was between 1963 and 1968. Meanwhile the Flood continues to be offered more Fluxus than it is capable of warehousing. Rub has had to turn down an old V.W. microbus that had been converted into a work of art called the Fluxmobile. (In what may be seen as the last great Fluxus bargain, the Fluxmobile was sold to a struggling artist for $500. He needed a car.) So how does one know where to draw the line?

"Would we keep the remnants of the piano?" asks Rub with a knowing smile.

"No, of course not," he answers himself. "That would be silly."

Flux-artist Corner "demystified" the Hood Museum.

Current price for FluxusYearboxes is $15,000.

Fluxmaster Maciunas pointed theway to art's boldest experiments.

Jan van der Marke guidedFluxus to Hanover.

Fluxshops, such as this one assembled byWillem de Ridder, had few paying customers.

Lee Michaelides is managing editor of this magazine.

The genre is called "FLUXUS," a movement part POLITICS and part practical JOKE.

The DISCRIMINATING reader may ask: Is this SOME kind of a JOKE? well, in way IT IS.

George MACIUNAS did try to IMPOSE some standardson the group. But, they IGNORED him.

The COLLECTION includes half of the original score for the "Young Penos SYMPHONY."

A FLUXSHOP that Maciunas ran in New York went an entire year WITHOUT selling a single ITEM.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

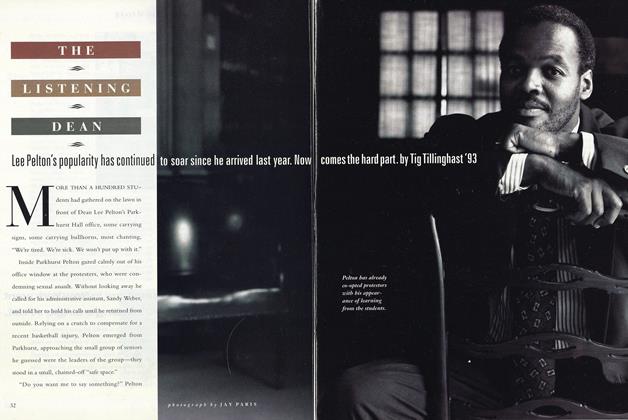

FeatureTHE LISTENING DEAN

October 1992 -

Feature

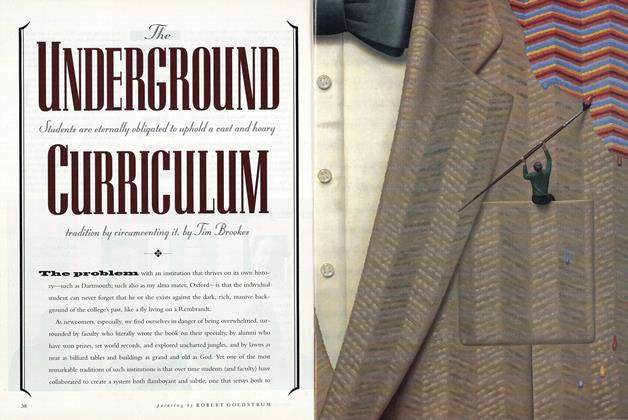

FeatureThe Underground Curriculum

October 1992 By Tim Brookes -

Article

ArticleThe Lost Season

October 1992 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Article

ArticleDid Something Happen in 1492?

October 1992 By William Spengemann -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

October 1992 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1985

October 1992 By Rick Joyce

LEE MICHAELIDES

-

Article

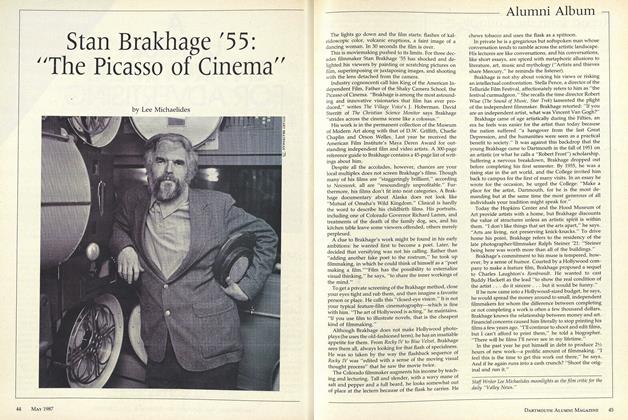

ArticleStan Brakhage '55: "The Picasso of Cinema"

MAY • 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Article

ArticleLooking Inward

December 1988 By LEE MICHAELIDES -

Feature

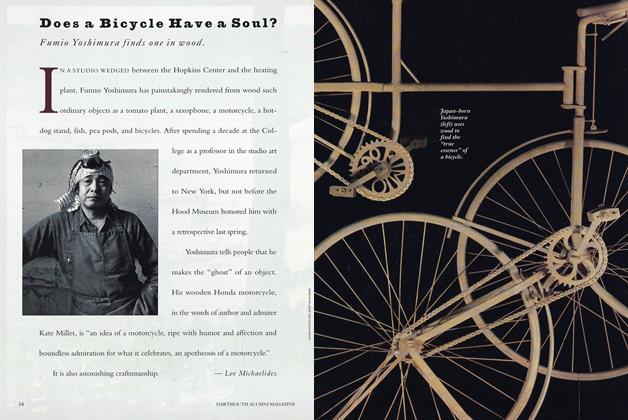

FeatureDoes a Bicycle Have a Soul?

June 1993 By Lee Michaelides -

Feature

FeatureForged by Flame

Nov/Dec 2005 By LEE MICHAELIDES -

Article

ArticleWhat's New

July/Aug 2010 By Lee Michaelides -

CAMPUS

CAMPUSWhat’s New

July/August 2012 By Lee Michaelides

Features

-

Feature

FeatureWhite House Fellow

MARCH 1968 -

Feature

FeatureVincent Starzinger Professor of Government 1,000 miles in o single scull

January 1975 -

Feature

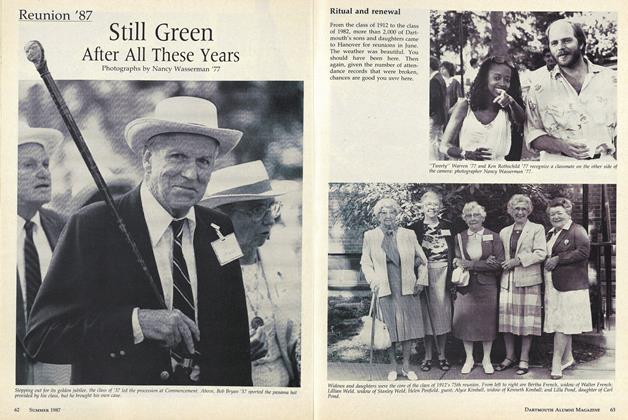

FeatureStill Green After All These Years

June 1987 -

Feature

FeatureShhh. There still are idealists abroad and they're called the Peace Corps

JUNE 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

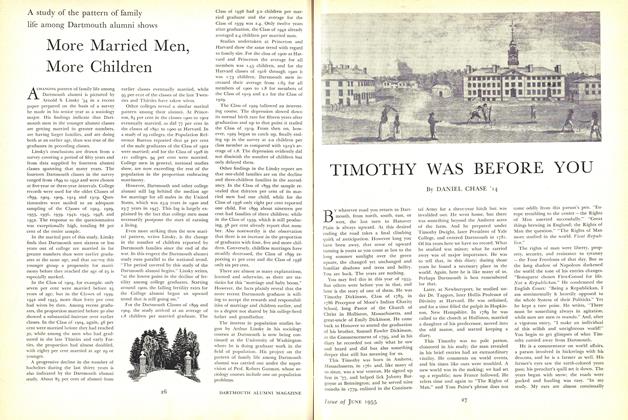

FeatureTIMOTHY WAS BEFORE YOU

June 1955 By DANIEL CHASE '14