Why do americans sue so much?Why is one of the original liberal arts obsure andmaligned today? Some rhetorical answers...The case for reviving rhetoric.

gress and a nation to believe in his ideas of the future. Americans have learned through bitter experience that good candidates do not always make good Presidents. If Clinton's election oratory showed off his ability as a leader, it was a peculiarly modern kind of leadership; it relied on a cadre of professionals skilled more in marketing than in rational forms of persuasion. The high points of Clintons acceptance speech at the Democratic convention had been pre-tested in national surveys. The drafting went to speechwriters—an accepted profession but strange when you think about it, like the medieval scribes of illiterate noblemen. The writers in turn harvested some of the most memorable phrases honoring the middle class "those who do the work, pay the taxes, raise the kids, and play by the rules" right out of the mouths of focus groups. The speech was successful, judging by the surge in popularity that lifted Clinton into the White House. It was a textbook campaign: marketing practiced as oratory with unequalled skill and protean volume. We also saw rhetoric in its old, classical sense the unsung art of reasonable persuasion, in which leaders spoke their own thoughts and sought a consensus. But we did not see much of this art.

After the convention Clinton boarded a bus to tour the nation, giving speech after speech and out-talking even George Bush, himself a tireless wordslinger. Bush countered by hopping a whistle-stopping train in imitation of Harry Truman, a President both candidates temporarily claimed as a legitimate forebear. Their true oratorical antecedent, however, was not Harry S. Truman but Gerald R. Ford, who cranked out a speech every six hours during the election year of 1976. Rhetorician Roderick, P. Hart of the University of Texas calls Ford "a rhetorical iron man." But even Ford was only following a trend. According to Hart, Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon each spoke roughly twice as often as their immediate predecessors. Eisenhower made 11.3 addresses per year; Reagan, our national master of ceremonies, made 52.8.

While this explosion of speech has proven successful in some campaigns it certainly didn't hurt Clinton's high-volume hortatory seems less effective once the candidate has made it to the White House. Judging from opinion polls, bills passed in Congress, and the outcome of elections, modern American Presidents appear to be no more persuasive than their relatively taciturn predecessors. Roderick Hart points out that, during the very period when Presidential speechmaking burgeoned, American voters expressed a growing sense of isolation from the political process. They felt "increasingly ignored," says Hart "spoken at but not listened to."

The irony is that our whole society has become more talkative, thanks to technology. We communicate more by word of mouth and less by line of type. While the electronics that carry all this verbalizing get more sophisticated, our public debates head in the opposite direction. We talk, but we don't reason together. Americans are unable to agree on the issues that divide us most AIDS, abortion, education, America's role in the world. The most logical form of modern persuasion lives not in the White House and Congress (or on Brinkley and Donahue) but before judge and jury. Because our political rhetoric has become notoriously empty, the judicial system has rushed to fill the gap; democracy abhors a political vacuum. Do not blame politicians or even lawyers (pace Dan Quayle, Esq.). The problem lies, mute and distrustful, at the feet of the American voter. Outside the courts we no longer believe in reasonable persuasion. In our politics we have substituted compromise the give and take of power for public consensus. In place of rational debate we have saturation bombast. Former Reagan aid Martin Anderson '57 wrote about his boss in the book, Revolution: "I watched him use that gift of speech like an F-14 Tomcat fighter plane, wreaking havoc on his political enemies and blasting new policy paths where others had failed." Imagine Lincoln's secretary, John Hay, describing the Gettysburg Address in those terms. But then, Hay and his mentor were the highquality product of a different democratic culture and a different educational system. And that is the crux of this essay.

Lincoln and his rhetorical mentor, Dartmouth's own Daniel Webster, studied the art of persuasion for years before they went into politics. They learned more than a skill for winning debates; they also acquired a faith that people can be brought to see the public good of a public decision a belief we have mostly abandoned. Those two great men were able by force of oratory (combined, in Lincoln's case, with military force) to bind together a loosely knit nation. As the saying goes, Lincoln did not just win the war, he won the argument. Before Webster and Lincoln, the United States was a plural noun. After them, the nation was singular. We could use that kind of political glue today. And our universities, once a bastion of classical rhetoric, are the first place to start.

If this wish for reasonable speech sounds naive, allow me a personal note. In nine years as an editor and reporter in Washington before coming to Dartmouth, I often found myself covering legislation environmental bills, mostly on Capitol Hill. My beat also included several federal agencies. Through countless committee hearings, interviews, internal reports, and off-the-record barroom chats, I learned that very little work in Washington is done by persuasion. It is done by power, and power comes less from vaunted electoral "mandates" than from money. Compromises rise out of dough. This is nothing new, obviously, but since the triumph of American prosperity after the World War I our nation's politicians have used informal deal-making often to the exclusion of other forms of policy-making. The question arises today: What happens when the money runs out?

An alternative to this system has been around for thousands of years. It is the art of argument, a branch of the discipline of rhetoric. Classical argument combines both the emotions the assumptions and prejudices so skillfully exploited by political marketers and the intellect. The art is fueled by a belief that society can distinguish between good and bad, and that a people can make those choices in common, can find a consensus. In America, argument was practiced best before and during the Civil War, when reason was needed the most when the nation was divided and compromise eventually failed utterly.

I had a vague notion that classical argument was once studied and admired not just for its political or historical value but for its own sake as an art and so, two years ago, I began doing some reading in the subject. I went to the library and found shelves and shelves of material, much of it unused for years. Few of the volumes had the bar-code strips that Baker librarians began putting on books seven years ago as they were checked out. When I hefted a couple dozen stripless books to the counter, the woman behind it exclaimed, "You must have discovered a new field!" It certainly was new to me. But many of the books written as far back as two and a half millenniaseemed remarkably familiar. For one thing, the very first rhetorics were handbooks in the art of suing.

THE ORIGIN OF THE HANDBOOKS CAN BE traced to a single moment in history: 467 B.C., when the people of Syracuse, Sicily, overthrew a tyrant called Thrasybulus and replaced him with a radical form of government, democracy. The idea of people ruling themselves was not entirely new; the Athenians had evolved the system over the previous century and a half. But Syracuse was not so patient about the matter. Thrasybulus had thrown many families out of their homes and replaced them with people loyal to the government. As in Eastern Europe today, when democracy came in, the displaced families wanted their property back. To untie the knots of ownership, the Syracusans began suing each other.

The problem was, they didn't know how to sue, having spent several millennia without a democracy or, the gods forbid, lawyers. So the people began by copying the Athenian system. Trials in Athens consisted mainly of a pair of speeches, one by each opposing side, in front of a huge jury of at least 201 citizens enough to give stage fright even to the righteous. (There were 501 jurors in Socrates's trial, for instance.) To increase the odds of novice litigators, teachers in Syracuse offered some coaching. Some of the teachers published handbooks which became ancient bestsellers throughout Greece. The books eventually branched out beyond judicial oratory into other forms of public speaking, including political argument. Freelance professors of oratory, called Sophists, set up schools to teach paying customers the tricks of the trade, including some practices character attack, indirection that give lawyers and politicians a bad name today. Even at this early stage, two and a half millennia ago, rhetoric began to develop an uneven reputation. It took on a certain... odor.

Smell and all, rhetoric is an unhappy democratic necessity. The world would be much purer if we all engaged in logical discourse, free of the stench of human emotion, and made the right choice in every public question. But the Sophists, admirably rational souls that they were, argued for several centuries and concluded that there is no universally correct choice in a public question. Human affairs, alas, do not lend themselves to the predictable but only to the probable. The Sophists came to distinguish between natural and human phenomena—between absolute natural laws and ephemeral reality. And so they earned themselves the nasty label that conservatives like to stick on academics today: relativists. In order to achieve a consensus, the Sophists said, parties have to be willing to find some common ground of belief, a decision that suits the circumstances rather than fixed principles. It was the Sophists who came up with the relativistic notion of public opinion. What was true to the multitude became a kind of temporary fact. A good Sophistic speaker starts with public opinion and coaxes it along to a different place. The Sophists were, in short, good democrats, which is why Socrates, who was not a good democrat, disliked them. The wise Socratic speaker knows the truth before he opens his mouth, public opinion be damned. Socrates held himself aloof from greedy rhetoric professors who charged for their wisdom; his own lessons were free. Then one day his best scholarship student opened a rhetoric school and began charging tuition. The student was Aristotle.

A RISTOTLE WAS NO SO phist, though. He did not teach persuasion simply for the sake of it. Instead he found a middle ground between the absolutism of Socrates and the smelly pragmatism of the Sophists. Rhetoricians are good at finding middle grounds; Aristotle was brilliant at it. As a young man he had become one of the greatest scientists of a scientific age; later in life his attention shifted increasingly from nature to human nature, to the politics and ethics of real people. Aristotle had the scientist's skepticism of manipulative speech, and he believed that in any given situation there was a right and a wrong decision. "Truth and justice are more powerful than their opposites," he said. When society takes the wrong decision, "the speakers with the right on their side have only themselves to thank for the outcome." Given a fair match between two good debaters, the truth will make itself understood. In fact, he maintained, the truth has its own built-in argument that only awaits discovery by the speaker. Aristotle defined rhetoric as "the faculty of discovering in the particular case what are the available means of persuasion." Following the habit of a good scientist, he listed a number of those means in what is the most influential handbook of oratory ever written. Aristotle's speaker has three kinds of persuasion at his disposal: the logic of the argument, the emotions and attitudes of the audience, and, most important, his own character or, rather, the audience's impression of it. The good speaker can reason logically and knows a thing or two about psychology. In a perfect world, wrote Aristotle wistfully, cases should "be fought on the strength of the facts alone." But"the sorry nature of the audience," that unpredictable human nature, makes it necessary to employ a few psychological techniques. Aristotle's brand of political argument does not bomb and strafe like Reagan's rhetorical fighter plane. It finds some common ground among the assumptions of the audience, and even among those of the opponent. The point of the debate is not merely to win an argument but to decide the best course of action a society should take. The outcome, either in court or in the legislature, becomes a kind of public knowledge all its own a truth that the majority of citizens accept. In other words, a consensus.

Aristotle did not have the last word. The two poles of argument Socrates's and the Sophists' continued right on through Roman times and the birth of Christ. Their temporary juncture lay in one Roman, Cicero, who was considered by peers among them Julius Caesar to be the greatest speaker ever. Cicero, like Aristotle, wanted to fuse the thinking of the philosophers and the Sophists, and he wrote rhetoric textbooks of his own to make the combination stick. Cicero came up with five "arts" of rhetoric: Invention, Arrangement, Style, Memory, and Delivery. These arts came to form the core of Roman education; modern liberal arts would not suffer if they were organized along similar lines.

Invention for Cicero is the discovery of the correct arguments for the occasion, and Arrangement is the organization of those arguments. Style is the composition of the language itself. Memory lets the speaker work without a teleprompter (the ancients had a love-hate relationship with writing, fearing its erosion of people's ability to remember). And Delivery, said Cicero, is the control of voice and body. He would not have given Reagan high marks; Cicero placed greater emphasis on Invention than on Delivery. "Wisdom without eloquence has been of little help to states," he wrote. "But eloquence without wisdom has often been a great obstacle and never an advantage." Cicero, like Aristotle, wanted to find a common ground between philosophy and manipulation, and between nature and human nature. Like Aristotle, Cicero liked to bridge divisions. His writings were to have a powerful effect on the ancient guides that were written after him. Wherever there was democracy, there was rhetoric. It was taught over many centuries, acquiring an educational momentum that kept rhetoricians employed even when democracy declined and despotism reigned. But then came Christianity, a great spiritual revolution that yanked rhetoricians back toward Socrates's eternal-truths point of view.

THE GREAT FACT OF THE CHRISTIAN GOD and the revealed knowledge of the Scriptures precluded finding some temporary truths among human beings. The Christian rhetorician did not persuade; he proclaimed. Cicero's "invention" the art of discovering the logical means of persuasion became a matter merely of understanding the existing biblical truth. And so, under Christianity rhetoric lost many of its logical and philosophical underpinnings and became a matter of style, a corpse, said one critic, in brilliant clothing. Yet the Sophistic art did not die out entirely. Professors continued teaching the discipline throughout Europe, and public disputation arose with democracy in the city-states of Italy between the eleventh and fourteenth centuries. Medieval cathedral schools in England and France taught rhetoric for application in preaching and letter-writing, and in the thirteenth century Aristotle's Rhetoric was translated into Latin and used throughout Europe as a textbook. When the printing press arrived, classical rhetorics Cicero's in particular were among the first to be printed. As law courts developed through medieval times and the Renaissance, argument began to be seen as a practical art with a political purpose. But then came the second knockdown punch, after Christianity: the rise of modern science.

The great political and natural scientists of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries rejected the Sophists' (and Aristotle's) distinction between natural and human science. Scientists such as Rene Descartes thought it perfectly likely that human behavior would someday become utterly predictable. They declared "probable and "contingent" truths to be anathema. Said Descartes, flatly: "We reject all such merely probable knowledge and make it a rule to trust only what is completely known and incapable of being doubted.' Stripped of its usefulness, the academic study of rhetoric slid further into a bad habit common to fields that are uncertain of their own worth: the proliferation of jargon. Most notorious among rhetorical terms are the figures of speech combinations of words for emotional effect. The Greeks came up with a few of them, the Romans many more. The terms are often useful in analyzing skillful language. Metaphor and alliteration, for example, are figures of speech. But by the seventeenth century, the field was collapsing under their weight. There was the redundant epanalepsis ("Year chases year, decay pursues decay"), the run-on anadiplosis ("For want of a nail the shoe was lost, for want of a shoe the horse was lost..."), along with chiasmus, antisthecon, proparalepsis, epanaphora, pereklasis, paradiegesis, and a raft of other picked nits and obesities. When William Shakespeare Was in grammar school, children had as many as 200 figures to memorize. The Bard did not forget his rhetorical education; in Hamlet he had Polonius abuse an antimetabole: "'Tis true 'tis pity, and pity 'tis 'tis true, a foolish figure but farewell it, for I will use no art." By Samuel Butler's time in the eighteenth century the technical study of rhetoric was already on the wane, but he still could complain in a famous couplet: "All a rhetorician's rules / Teach but the naming of his tools." No longer was formal argument a means for uncovering the truth in a public situation; it became an art of showing off, even of obfuscation. The scientists wanted nothing to do with it, and who could blame them? The English Royal Society adopted a resolution requiring members to use "a close, naked, natural way of speaking." They meant this language to be in opposition to rhetoric.

But plain speaking is not opposed to rhetoric. To the right audience, unadorned speech can be more persuasive more effectively rhetorical than ornate speech. The Royal Society's real linguistic complaint was not just about style; the scientists argued against Sophistic argument itself. It was deja vu all over again, Socrates vs. the Sophists. In this corner: the Christians and scientists, who held that the outcome of every righteous debate was fixed ahead of time; to them, rhetoric was legitimate only when it served an established and permanent truth. In that corner: the Sophists' legal and political descendants, who believed that the truth was a fragile and temporary phenomenon determined through argument. Speakers plain and fancy have fallen into both camps through the ages. Two sterling examples of the argument school were the silver-tongued Daniel Webster and the plain-spoken Abraham Lincoln.

WEBSTER WAS A man of reason and a man of style, We're talking style. To understand his impact as more than just a public figure, imagine him striding to the podium like an opera singer, barrel-chested, trained in all the classical gestures, his black "mane" of hair (as observers liked to call it) covering his massive head, his dark eyes fixed in a gleaming stare. He embodied what Aristotle had called the most important persuasive element in an argument: ethos, or character. Webster's was hardly the kind of ideal character we think of today. He was a politician on the take with major corporations, a married man with a fondness for young actresses, a tippler with a portable bar called his "Traveling Companion." Forget Moscow trips and inhaling: George Bush, that guardian and exploiter of "character issues," would have made scandal hash of him today. And, in fact, those very "issues" probably kept Webster from making a successful run at a Presidential nomination. But most of his constituents were willing to indulge him; his sins were the peccadilloes of pagan gods, and Webster was as godlike as man could become. After one of his speeches, dignitaries would find themselves too timid to stand close. It was, they would say afterward, like being next to a deity.

Webster did not just deliver political speeches; he delivered history, and his audiences knew it at the time. Like the great rhetoricians of old, he was a master at pulling together separate realities. For a time he knitted an entire people, and he prepared the way, philosophically, politically, and rhetorically, for the self-taught scholar who combined military power with rational persuasion, Abraham Lincoln.

How did Webster do it? Where did he learn the art of moving audiences, of composing addresses that have the subtlety and lasting shine of literature and the street wisdom of politics? Genius as he was, Webster was also the beneficiary of a curriculum that had been taught in American schools and colleges from the colonists' first arrival. Much of what he learned, that New Hampshire farmboy and Exeter preppie, he learned at Dartmouth.

The College's first Commencement in 1771 included speeches in English and Latin as well as a formulaic Latin "syllogistic" dispute that must have mystified the area farmers who flocked to the occasion. Even the one English oration by senior Sylvanus Ripley must have caused some head-scratching. Its style shows why rhetoric had already acquired a shaky reputation in Europe. "No sooner is the happy Stranger arriv'd on their Coasts, than Oratory breaks forth from the shades of Ignorance & the Charms of Poetry and polite Literature grace the barren mount of Parnassus," gushed young Ripley. By Webster's time, Latin speechmaking was supplemented by the forensic dispute, which, to the vast relief of both students and audience, was conducted in English. Topics included such national issues as slavery, tariffs, freedom of the press, and women's rights. But while these exercises were sanctioned by the College and were even part of the curriculum, the students saved their oratorical passion for debating societies, an extracurricular activity that had little to do with the faculty or administration. Three of the groups sprang up at Dartmouth. They met weekly for formal and extemporaneous debate, and they showed off their members' skill during Commencement Week. The top speaker in each group including Webster, champion of the United Fraternity was a big man on campus. Webster was well prepared by a system that had broadened the intent of education beyond the ministry to include the lawyers and statesmen who were to provide the nation's second generation of leaders. His college courses included extensive reading in classical rhetoric the great orator Demosthenes, Cicero, textbooks by the Roman master Quintilian, modern English and French rhetoricians. By the time he graduated he had delivered at least six orations under the eye of rhetoric instructors who graded his performance. He had participated in syllogistic disputes in Latin, forensic exercises in English, and weekly debates with his club. Rhetoric, in short, was his "major" before there was such a thing as a major. His college had prepared him for a career as America's greatest living orator. And Dartmouth, as every graduate knows, was well repaid. While Webster was the most brilliant result of a formal rhetorical education, however, he also represented the last generation of classically trained orators. The curriculum was to go out of fashion in a remarkably short time; within two or three decades, the kind of training Webster had gone through would become virtually unknown, not just at Dartmouth but throughout the nation.

RHETORIC DIVORCED FROM MEANING IS empty rhetoric, and that is what it became in American universities after the Civil War. Academic specialization is partly to blame. Argument is by nature interdisciplinary, even superdisciplinary. It combines where other fields split. As English departments began to form in American colleges, including Dartmouth, rhetoric became isolated. The field gradually lapsed into a study of "elocution," a field that stressed science over art. One of the most extreme examples was at Harvard, where an instructor devised a sphere made of bamboo slats that he fitted over students to make them gesture more precisely.

After the turn of the century, a few pioneers attempted to merge again the fields of contemplation and public action in a classical sense. One of them was James Albert Winans, a Cornell professor whom President Hopkins persuaded to come to Dartmouth in 1920. Winans combined the classics with modern psychology, using such thinkers as William James to update the philosophies of Aristotle and Cicero. And Winans helped launch a rich field of rhetorical research that continues to grow.

Composition instructors rediscovered the field during the sixties, when Edward P.J. Corbett published a superb textbook, Classical Rhetoric forthe Modern Student. Corbett used actual speeches, ranging from ancient Greece to modern times, to illustrate the ways in which the old art is relevant today. The text was studied at Dartmouth, where four professors taught as many as seven courses in speech at any one time. But this revival was not to last long. In 1979 the College faculty voted to abolish the Speech Department and replace it with an "Office of Speech." Two professors were dismissed. The reason cited was that a whole department was not needed to teach public speaking. The notion of reinstituting studies in rhetorical theory received some interest by a committee that was asked to look into the matter that same year. But they decided that such an emphasis would require scarce new resources. Besides, the committee said, Harvard, Yale, Amherst, Williams, Middlebury, and Tufts did not offer any courses in speech. The faculty succumbed to the self-fulfilling logic of the Ivy League: if it isn't done at other schools, why do it here?

A COUPLE OF YEARS AGO I WOULD have said good riddance. The country is already fall of rhetoric as it is; why waste precious tuition dollars to teach it? But now, after my romp through the history of the field, the opposite seems true to me: Americans do not have too much rhetoric but too little, in the classical, reasonable sense. We complain about being manipulated by advertising and political campaigns and then allow ourselves to be seduced. We decry endless speechmaking and then put up with it daily. We yearn for real leaders, men and women who can grasp the desires of the nation and take them some place greater, and then we distrust the very possibility of consensus.

Still, it is hard to imagine a democracy without well-practiced speech. If we scorn rational persuasion in our government and our talk shows, it will seek an oudet of its own. Argument will find its place. And, in fact, it has found a niche, in courtrooms where decisions become (after the appeals are exhausted) a Sophistic public truth. Even when this process fails when important elements of society refuse to accept a courtroom verdict, as in the Rodney King case the anguish and outcry show that Americans want the law court to be the bastion of fairness and rational deliberation.

Beyond the courtroom, this notion of consensus is difficult to sell in a society that holds as its dearest tenet the sover eignty of the individual. The eighteenth-century philosophers who helped shape the modern American state including John Locke, who was a rhetoric professor for much of his career believed that self-interest would naturally lead to proper social decisions. Locke's public interest is an amalgam of individual preferences. Our government operates under that faith today, except that the sovereignty of the individual has largely been replaced by the sovereignty of the group. "The prevailing ideal casts government as problem solver," says Robert Reich '68, a Harvard economist, Dartmouth Trustee, and Secretary of Labor. Reich explains that under the current system officials seek compromise between interest groups, or they try to maximize the benefits of one while minimizing harm to the other.

Reich heads a school of thought among policy analysts that proposes an alternative, which he calls the "power of public ideas." Instead of relying exclusively on polling and on marketing surveys, instead of balancing the pleadings of special-interest groups, Reich and his colleagues make the case for public deliberation in national decisions. "Policy making should be more than and different from the discovery of what people want," Reich says. "It should entail the creation of contexts in which people can critically evaluate and revise what they believe." Clinton's pre-Presidential economic summit is an obvious attempt at one such context. But public deliberation works to foster changes in belief only when the persuaders on both sides subject themselves to opposing suasion, when the wooer is willing to be wooed. This active and passive art is not instinctive; it must be taught.

AND WHAT BETTER PLACE THAN College? A radical change in the currriculum would not be needed. Parents can encourage their collegebound children to take courses in rhetoric, and students can demand that rhetorical studies go beyond mere speaking success to teach critical argumentative thinking. Demand may bring about an eventual increase in the supply of courses.

We educational consumers will need to be patient, however. More than academic inertia stands in the way of classical rhetoric. Too many academics see the field's greatest strengths as educational weaknesses: its multidisciplinary nature, and its real-world combination of theory and practice. And yet, a great many students are looking for just this kind of applicable theory. These are young people who love language and want to know how humans interact. These students are frustrated by the separation of ideas into territorial disciplines. They seek knowledge for its own sake, but they are also curious to know the ways that knowledge applies in the marketplace. They want to learn how general concepts apply in specific situations, how theories become practice, whether ideals can become reality. Many of these future-oriented scholars end up in marketing, journalism, teaching, politics, the law, and other fields where language and thought are practiced professionally. They are looking for something more than what they get in their courses, some outward direction for their studies. Rhetoric, that most outward-facing of disciplines, may be just what these students need.

Without an education in argument, they are missing out on one of the greatest intellectual skills. Society suffers from a lack of educated citizenry who accept the uses of debate, who want to be persuaded, and have the sophistication to avoid being manipulated.

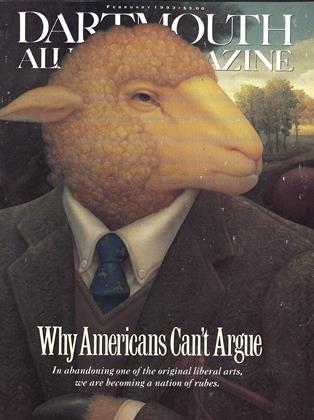

This last may be the academy's greatest lack. Skepticism is the vaccine that keeps our national rhetoric from turning malignant. Without it, we are a nation of rubes.

WEALREADY KNOW ONE THING ABOUT OUR NEW PRESIDENT: THE man can talk. The press swoons over his ability to string together complete sentences, a skill that Yalie George Bush lacked. The question now is whether Bill Clinton can argue whether he can persuade a Con

IN PLACEof rationaldebatewe havesaturationbombast.

Two and a halfmillenniaago, rhetorictook on acertain...odor.

ROBERTREICHand hiscolleaguesmake the casefor publicdeliberationin nationaldecision-making.

JAY HEINRICHS is the editor of thismagazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

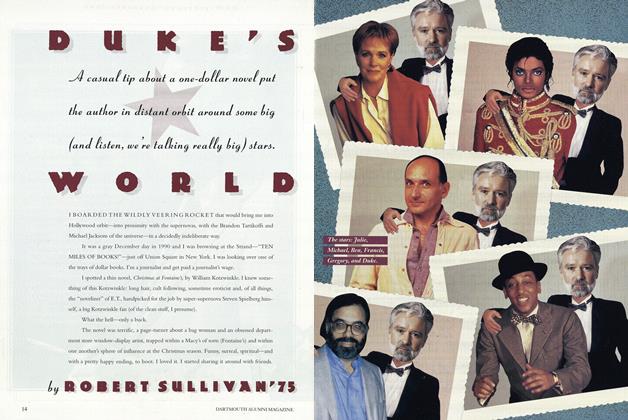

FeatureDUKE'S WORLD

February 1993 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

FeatureRoller Screaming

February 1993 By John Morton -

Feature

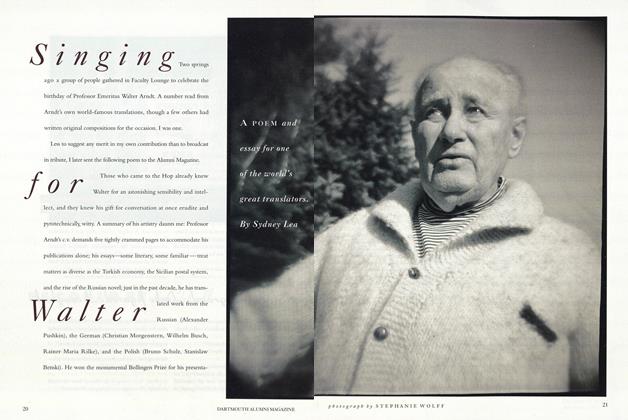

FeatureSinging for Walter

February 1993 By Sydney Lea -

Article

ArticleThe Idealist a Leader

February 1993 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleImagining the Orient

February 1993 By Douglas Haynes -

Class Notes

Class Notes1983

February 1993 By Kenneth M. Johnson

Jay Heinrichs

-

Feature

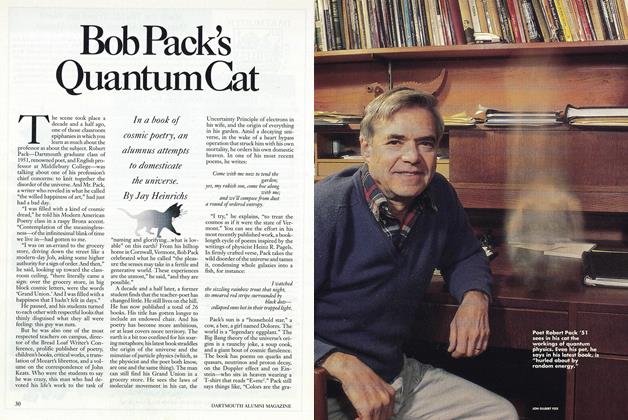

FeatureBob Pack's Quantum Cat

December 1989 By Jay Heinrichs -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Cross Section of Existence

MARCH 1992 By Jay Heinrichs -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChoices

September 1992 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleThe Review's Bedfellows Get Stranger

June 1993 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleA Book for Lovers of the Raucous Side of Dartmouth

May 1994 By Jay Heinrichs -

Outside

OutsideRunning With Wild Abandon

July/Aug 2002 By Jay Heinrichs

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTRUSTEES SANCTION A FOURTH TERM

OCTOBER 1962 -

Feature

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT 1971

JULY 1971 By CHARLES J. KERSHNER -

Feature

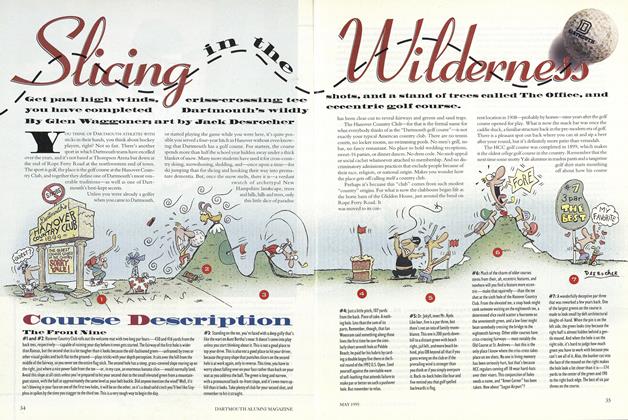

FeatureSlicing in the Wilderness

May 1995 By Glen Waggoner -

Cover Story

Cover StorySecond Nature

OCTOBER 1996 By Jay Heinrichs -

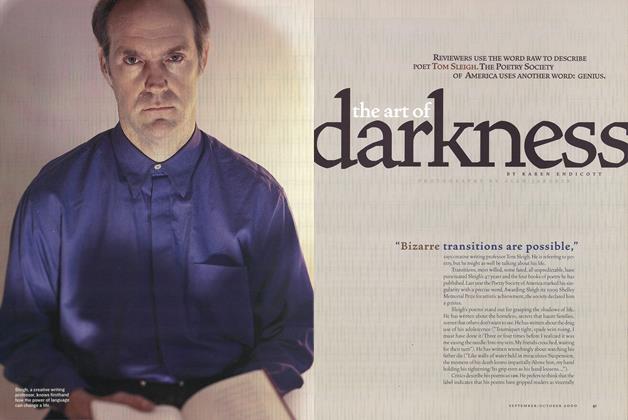

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Art of Darkness

Sept/Oct 2000 By KAREN ENDICOTT -

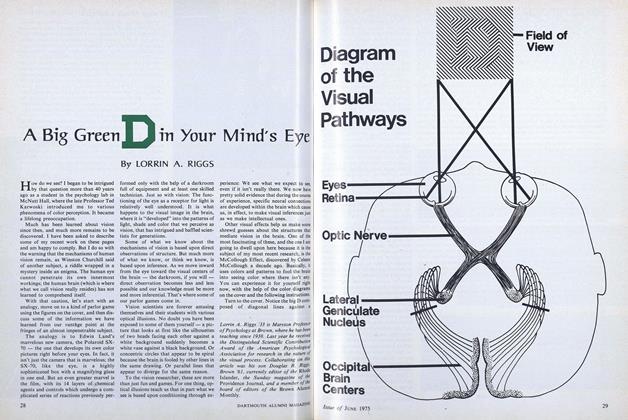

Feature

FeatureA Big Green D in Your Mind's Eye

June 1975 By LORRIN A. RIGGS