Braving MUD and Gopher, a reporter PLUNGES INTO THE VAST JUNGLE DFTHE INTERNET AND BRINGS BACK EXPLDDING GUPPIES, PARALLEL UNIVERSES, AND THE MDRMDN DIET.

I AM IN THE OFFICE at a ridiculously late hour for a family man, checking my e-mail. With a mouse I click on the computer screen s "in" box. A few notes are from my co-workers, but oh, joy! 19 come from computers on university campuses all across the country. A computer talk channel called a listserve has been created for people like me who edit publications for educational institutions. More than a hundred of my professional colleagues have signed on, and I am eager to see what they have to say about public attitudes toward academia, about the hot world issues of the day, about the newest layout software. I shall be lonely no more.

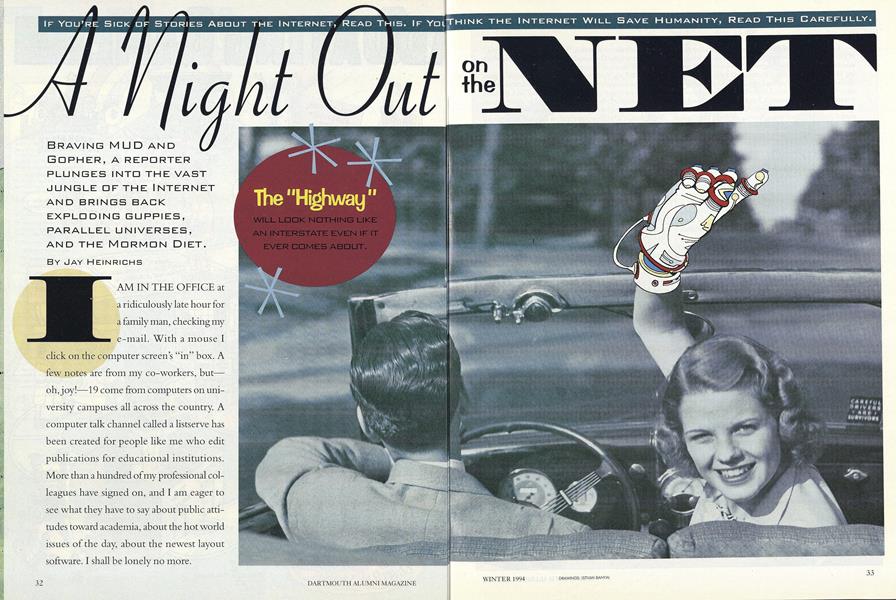

I am fishing in a small part of a vast and expanding ocean

of electronics called the Internet, harbinger of the Information Superhighway. The "Highway," which will look nothing like an interstate even if it ever comes about, is a vague catch all term for everything that is being developed by the communications industry. Meanwhile there is the Internet, a casual confederacy of some 2.3 million mainframe and personal computers around the world, encompassing an estimated 20 to 50 million users. Among the most popular features are the electronic bulletin boards, in which messages are posted onto a big computer somewhere, available to anyone who directs a personal computer to read the messages. Our editors' listserve is more aggressively communicative: When someone writes a note to our group, a powerful mainframe computer at that editor's institution zips it over the national phone lines to Michigan Tech, where this particular talk channel is centered. Each of the institutions on the Internet pays for the phone connections and the hardware including the vast amounts of data storage necessary to file and route all the uncountable messages on the Net. (If you have paid either tuition or taxes at some point in the past couple of decades, chances are very good that you have contributed to the Internet.) After the computer in Michigan receives the editor's note, the machine shoots it to big computers at each member editor's institution. Those mainframes alert each recipient's personal computer that the message has arrived. Bingo: a few seconds is all it takes. The Postal Service should work so well.

But then, all the Postal Service asks of you is a modicum of literacy and a 29 cent stamp. Mailing something on the Internet requires a somewhat larger investment: say, a thousand bucks for a computer. Plus a communication device. Plus software. Plus the phone connection. Plus some sort of "gateway" that lets you into the Internet itself. Commercial services usually charge by the hour, which can cramp your style if you're just goofing around. Your best bet is a network linkup on your office computer so you're not personally paying for your Internet passport. Then you must bribe an adolescent male to help you figure it all out. (Only ten percent of Internet users are over 40, and males predominate.)

Or, better yet, buy a book by a young Cornell grad named Adam Engst. Engst is an Internet evangelist. He even e-mails his parents. But he is mostly known for the best-selling book, Internet Starter Kit. It is to the Information Superhighway what the Gideon's Bible is to lonely travelers. Which is a good moment to describe the genesis of the Internet; cybervangelists like Engst make you speak of the Net in Bib- lical terms.

In the beginning there was Harry Bates, an 1879 Thayer School graduate. (Yes, we're talking ancient history.) In 1890 the United States Census did use his electrical punch-card machine, which begat the Tabulating Machine Company which begat IBM. In 1940 Bell Laboratories mathematician George Stibitz did conduct the first public demonstration of remote computing by connecting a terminal at Dartmouth to his headquarters' "automatic calculator" in New York. In 1962 Dartmouth mathematicians john Kemeny and Thomas Kurtz did solve a mathematical problem simultaneously on two terminals, and they were sore amazed. "2+2=4" the print out said, and the creators said, "Let there be Time Sharing." And there was the Dartmouth Time-Sharing System which did spread terminals throughout the land.

In 1967 the Pentagon begat the first netwprk of giant mainframe computers, joining together its military research sites to share scarce and valuable equipment (and, in classic defensive strategy, disperse its targets). And 10, a pair of graduate students at Duke married computers to computers in 1979. And in 1981 there appeared on the earth the personal computer, and offices and dormitory rooms did lie down with the mainframes and know them.

In 1984 was born the Apple Macintosh, and Kemeny saw that it was good, and Dartmouth did become the first college to wire every dormitory room directly to the network and electronic mail.

And there followed other networks between mainframe computers and supercomputers. The mainframes begat bulletin boards and local area networks and e-mail systems and searchable databases, and chaos ruled the land.

As confusing as it is, if the Information Superhighway ever becomes a reality, it will follow the meandering cowpath of the Internet. Some weeks ago I decided to wander into this electronic future to see if it works.

So one night I stay late at work. I first do what Dartmouth students do when they come to campus: I link my Macintosh up with the mainframe computers in Kiewit and find an electronic file folder called "Incoming Student Software." Among other things, this file contains all the goodies a student needs to begin exploring the Internet on and off campus: electronic mail, library and database searchers, a program that lets students buy or swap used books, printing and language programs, and programs for exploring and getting stuff from the Internet. I grab a couple ofprograms (actually, I sit and wait for more than an hour while Dartmouth's slowmoving network sends me the software) and plug in.

What I plug into is hard to describe exactly; the Internet exists only virtually, like quantum physics or complexity theory. It is in no one place, no one owns it, it was never planned except at its beginning several decades ago; it is organic, ever-changing, and almost completely anarchic and so it is exixanelv metaphor-intensive.

Metaphor No. 1: The Internet As Nervous System

My education-editor discussion group is classic Internet stuff, an obscure nerve on the ganglion of global computer communication: The group has been set up by a gregarious editor at Seattle University, with the help of a guy at Michigan Tech who has the necessary software and access to his university's memory banks. Our listserve is small potatoes; some have subscribers numbering in the thousands.

I open the first message. It is from a female editor at a West Coast research university who offers to dance with any other editor who is over five-six.

A male editor at a Midwestern school wonders whether that includes slow-dancing.

Another male editor, at a Catholic university, says the

nuns told him that he and his dancing partner should leave room between them for his guardian angel.

Another editor at another Catholic university says the nuns told him it was not an angel but the Holy Ghost.

The dancing editor on the West Coast says she was brought up by cowboys who didn't care how far away anybody was as long as there was room to spit.

Other editors ask where the dancing editor would like to dance, and still others complain that they're sick of the whole conversation and to please stop loading up people's mailboxes with such trash.

All of which consumes 19 messages. So much for my

metaphor about the Internet being a vast nervous system zapping important signals around the world. All too often it's more like:

Metaphor No. 2: The Global Watercooler

|NV«|HI< INTERNET COVERS two basic aspects of I ' communication: conversation and libraries. J1 _ People can use their computers to talk to each other with a myriad of devices, including e-mail, so- called real-time conversation, and a complex of bulletin boards. These devices have their own arcane jargon and so- cial mores, but basically they're all just people talking with one another. A lot of computer fans somehow think that if enough people simply talked to each other, the whole world would be more peaceful and prosperous. These undoubt- edly are the same people who in the seventies wanted to buy the world a Coke.

After reading my e-mail messages, I fire up some software that allows me to check out some of the 2,000 bulletin boards on the Usenet, where people can post messages for anyone else to read. I browse through a bunch of them.

In a discussion group having to do with badgers (alt.animals.badgers), I read this poem: Fish, fish, badgers and fish, It's good to distinguish 'twixt bad- gers and fish! The badger's the one that goes GRRRRRRRR! And the one that goes *squish* is the fish.

I leave badgers and enter a bulletin board that offers help in using the Usenet. There I find instructions, un- derstandable only to someone under the age of 20, on software for navigating the Internet:

"NcFTP is to plain old ftp as Unix shells like bash, ksh, and tcsh are to sh and csh. Once you know what site you want to access—for which archie or Gopher may be needed—NcFTP makes brows- ing and retrieving files easier than ever, especially for Internet/Unix novices." Right. I change the channel.

On another board, a man named Dan D. has posted these instructions for communicating with a parallel universe: 1) Write message on paper 2) Stuff paper inside sock 3) Put sock in dryer.

The later the night gets, the faster the messages seem to come into the bul- letin boards. The charges for using for- profit "gateways" to the Internet tend to be lower at night; besides, who has time to do this stuff during the day? Just past midnight I come across a newsgroup called alt.folk- lore.science, which contains an interesting discussion of explod- ing guppies. A David Adams asks, "Do guppies' stomachs really explode if you feed them too much?" A man suspiciously named Jim Pike has an answer: "I fed a fish too much once. It ate until its stomach ripped open. But I don't think there was an actual explosion."

In the course of the night I learn in general that the five most popular bulletin boards include two on how to use the Internet and three on sex. Sports is another big topic, of course, with cricket being the number-one athletic sub-group. Here is a sampling of newsgroup names described in Adam Engst's Internet Starter Kit.:

soc.culture, esperanto rec. games. mud. diku nerdnosh rec.nude rec.org.mensa alt.alien.visitors alt.best. of. Internet alt.bitterness alt.chinchilla alt. conspiracy alt.devilbunnies alt.folklore.college alt.pave. the. earth alt.polyamory alt.sexy.bald.captains (a Startrek group) alt. slick. willy. tax. tax .tax alt.spam alt.stupidity

All of which leads inevitably to the next metaphorical substitute for Information Superhighway:

Metaphor No. 3: THE INFORMATION BOARDING SCHOOL

Where but boarding school and the Internet would you find such latenight talk about sex. Ivy League schools, and exploding guppres? Where else would there be enough foreign students to hold an animated discussion of cricket? In fact, the Internet is custom-made for male adolescents. You can talk pretty much about whatever you want, and play weird games in which people assume alter identities and explore electronic castles together, and no one can tell that you have acne and braces. The castles and fake identities come into play with MUDs, which stand either for Multi-User Dungeons or Multi-User Dimensions, depending on whom you're talking to. These are accelerated bulletin boards in which short messages fly fast, sustaining a multi-level conversation. It is like a party held in the dark.

I try out a fantasy MUD like the game Dungeons & Dragons. I follow the conversation for a while—-people assuming identities and moving in and out of castle rooms and realize I don't understand a word of it. People are talking about wibbling, ROTFL, Spam, IRL. Either those are real words that mean something to somebody or I'm hallucinating. Maybe it's that the little clock on the corner of my computer screen says 4:20 a.m., and birds are beginning to chirp outside my window, a hint of a dawning real world more compelling than the virtual one indoors. Navigating the Internet allows for a degree of control impossible in nature, but it is an arcane, frustrating, and heavily coded process, the kind that makes me gasp for air and that puts teenagers in ecstasy.

Mefaphor No. 4: THE INFORMATION SUPER-ATTIC

There is a vast and burgeoning amount of data on the Internet, from stock information to classic novels to dirty pictures. What exists will amaze you, it you can find it. But chances are, you won't. The Internet is, in short, like your attic, except that it is a billion times bigger and the "light bulb"—in this case, your software—is awlully dim. But lam a professional writer on assignment, and so, as cars begin to head down the streets of dawn for the coffee shops, I open the electronic door and walk in.

Looking for nothing in particular, I discover this excerpt from a story byjohnj. Clayton in the erotic journal Yellow Silk: "Never the faintest whiff of fetishist in me. No secret cache of size 6 stiletto heels makes me moan, no rubdowns with hissing silk and lace, and as for those costly voices in the night...."

I find several dozen drinking games, with such titles as "BatBee," "Beer Bungee," "Beeramid," and "BEERchesi," with rules so complex that one must either be a sober genius or a normal person too drunk to care. One of those most highly rated by the Internet reviewers is a game called, charmingly, "Brain Damage."

I learn from a geography database that the town I live in, Etna, New Hampshire, has 603 residents, that its average elevation is 782 feet, and that its global location is 43 degrees 41 minutes 34 seconds north latitude and 72 degrees 13 minutes 20 seconds west longitude.

I come across the Electronic Newsstand, a free service on the Internet that contains excerpts and some full texts of some 40 magazines, ranging from The New Yorker to Out Magazine. The service is a joint venture between The New Republic and The Internet Company, a private concern based in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

I find some useful reviews of vegetarian cookbooks, including a bibliography by Michelle Dick, owner of the FATFREE Vegetarian Mailing List. Listings note whether the books are vegetarian, vegan, lacto, or ovo-lacto. An entry I may not read: The Mormon Diet.

And I find lots of humor, the kind I once appreciated injunior-high gym. As in gym, most Internet humor consists of jokes funny only to the people telling them. Here's a corker related by Daniel P. Dern, editor of the electronic magazine Internet World: 'About a year ago," he writes, "the com-priv list had a spate of slogans for the CIX (Commercial Internet Exchange); without identifying the guilty parties, here's a few of the contenders: 'But...we get no CIX to route 56 [kbps]!'...'CIX are for TRDs.' (Transit Routing Domains)."

Stop it, Dan, you're killing me. Getting to sort through this wonderful flotsam and jetsam of humanity makes you sympathize with net gurus like Adam Engst, who favor the anarchy of undigested conversation over the Internet's gargantuan library archives. Who wants editors putting a spin on things anyway?

But wait a minute: I am an editor. I happen to like the process of digestion, and there are usefully edited' works on the Netbook reviews, for example, or, in increasingly frequently cases, books themselves. Encyclopedias. CIA information about the economies of third-world nations. (Which comes in handy when you want to compare your net worth with that of, say, Burundi. Here's an Internet-gleaned fact: The average Ivy League alum makes one fourthousandth of the annual budget of that African nation. I found that little data gem at 5:17 a.m., and it seemed even more amazing at the time.) You can do all this, too. For instance, a piece of free software called Gopher, available from the University of Minnesota (through the Internet) lets you search the Baker Library catalogs from anywhere in the world, or look up an e-mail address at the Slovak Academy of Sciences, or learn new song lyrics.

In other words, if you spend much of your life writing papers for junior high (or for Dartmouth, for that matter), the Internet databases can be very valuable. Professional academics find it useful as well, though the demand for international academic symposia in pleasant cities has not seemed to slacken. If you do not happen to be in junior high school or higher education or the news media, you might find the Internet somewhat less useful. The people who first knitted the Net together were certainly not thinking, "What the average world citizen needs is instant access to gossip and barrels of unsorted information."

But as a media type, I have to admit that, for me, the In- ternet is a pretty good thing. Among the improvements to my life over the past couple of decades, I rank global con- nectivity right up there with cheap digital watches and air- port cash machines. I can communicate instantly with friends and colleagues around the world without dealing with those endless voice-mail messages. I can conduct interviews with otherwise-inaccessible people. I can sound infinitely more erudite than I actually am, diving into databases for facts that will fill out the skeleton of knowledge I have on a story. I can...l can do this story!

And sometimes my research actually has been useful. Last February I was working late when it suddenly occurred to me that it was Valentine's Day, that my wife expected me home in 20 minutes, and that I had done nothing about the occasion. The stores in Hanover had closed an hour before. My brain was fried, so impromptu poetry or a homemade card was out of the question. In desperation I turned to the Internet, directing my software to the Shakespeare database (which could have been on campus or in Stratford-on-Avon, it doesn't matter to the computer). My collegiate Shakespeare education, limited as it was, had informed me that the bard's most lovey-dovey sonnets were around the middle. So I launched a search for sonnets between numbers 30 and 60 that contain the words "miss," "far," "away," and "gone" (I had been traveling a lot lately). The computer instantly came up with the full text to Sonnet 44, which says, more or less, that if my body were thought I would be with you always. I hit the print option to send the sonnet (set in a Valentiney type- face) to the office printer, grabbed my coat and snatched the document as I closed up. Elapsed time: four minutes. I slid the poetry onto my wife's plate just before she entered the dining room. She looked at the sonnet, and then at me.

"So," she said. "You forgot Valentine's Day again."

Which brings me back to the moral of the story: the Information Super-Whatever may make things more convenient, but it will not in a million years change human behavior. Or mine, at any rate.

The "Highway "

THE PEOPLE WHO FIRSTKNITTED THE NET TOGETHER WERE CERTAINLY NOTTHINKING, "WHAT THE AVERAGEWORLD CITIZEN NEEDS ISINSTANT ACCESS TOgossip ANDBARRELS OF unsortedinformation."

THE FIVE most popular BULLETIN BOARDS INCLUDE TWO ON HOW TO USE THE INTERNET AND THREE ON SEX.

THE INTERNET IS LIKE your attic,EXCEPT THAT IT IS A BILLIONTIMES BIGGER AND THE"LIGHT BULB"- IN THISCASE, YOUR SOFTWARE- II IS AWFULLY DIM .

If Your're Sick of Storise About the Internet, Read This. If You Thing the Infernet Will Save Humanity, Read This Carefully

JAY Heinrichs is the editor of this magazine. He works on his lap-top while fishing, and doesn't like either result.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhat We Do Best

December 1994 -

Feature

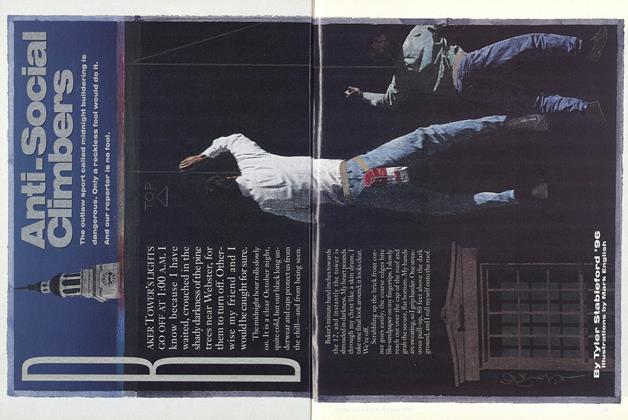

FeatureAnti-Social Climbers

December 1994 By Tyler Stableford '96 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

December 1994 By E. Wheelock -

Article

ArticleTied Up with Strings

December 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleThe Overarching Concern

December 1994 By JAMES O. FREED MAN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1957

December 1994 By Richard F. Perkins

Jay Heinrichs

-

Article

ArticleProfessor William Cole: "Fifty Years From Now They'll Be Talking About This Course"

MAY • 1988 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureOn a Freshman Trip, the Destination Is Community

MARCH 1989 By Jay Heinrichs -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTHE THIRD WORLD'S LOW-KEY CRUSADER

JUNE 1990 By Jay Heinrichs -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChoices

September 1992 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleThe Review's Bedfellows Get Stranger

June 1993 By Jay Heinrichs -

Cover Story

Cover StorySecond Nature

OCTOBER 1996 By Jay Heinrichs