ALUMNI VETERANS RECALL THEIR EXPERIENCES FIGHTING IN THE KOREAN WAR.

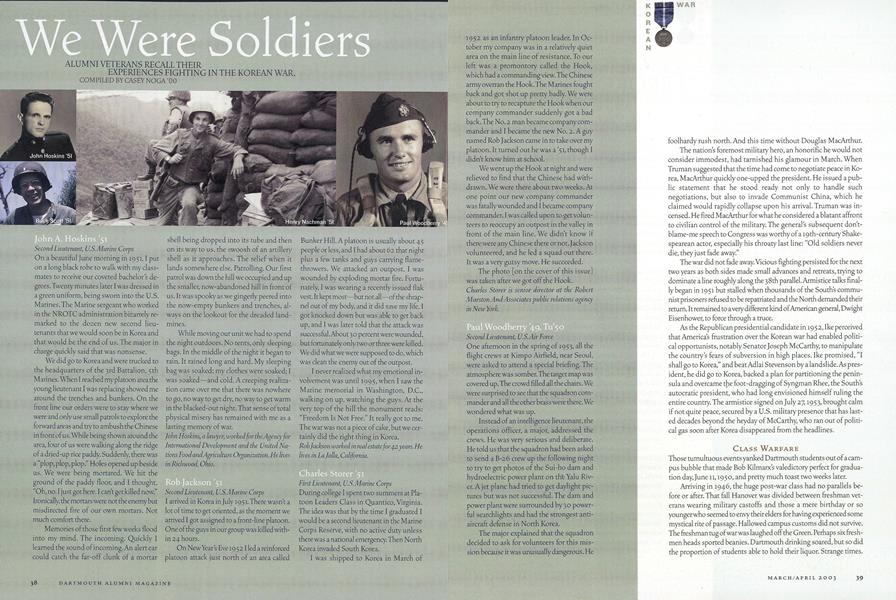

John A. Hoskins '51

Second Lieutenant, U.S.Marine Corps On a beautiful June morning in 1951, I put on a long black robe to walk with my classmates to receive our coveted bachelor's degrees. Twenty minutes later I was dressed in a green uniform, being sworn into the U.S. Marines. The Marine sergeant who worked in the NROTC administration bizarrely remarked to the dozen new second lieutenants that we would soon be in Korea and that 'would be the end of us. The major in charge quickly said that was nonsense.

We did go to Korea and were trucked to the headquarters of the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines. When I reached my platoon area the young lieutenant I was replacing showed me around the trenches and bunkers. On the front line our orders were to stay where we were and only use small patrols to explore the forward areas and try to ambush the Chinese in front of us. While being shown around the area, four of us were walking along the ridge of a dried-up rice paddy. Suddenly, there was a "plop, plop, plop." Holes opened up beside us. We were being mortared. We hit the ground ot the paddy floor, and I thought, "Oh, no. I just got here. I can't get killed now." Ironically, the mortars were not the enemy but misdirected fire of our own mortars. Not much comfort there.

Memories of those first few weeks flood into my mind. The incoming. Quickly I learned the sound of incoming. An alert ear could catch the far-off clunk of a mortar shell being dropped into its tube and then on its way to us, the swoosh of an artillery shell as it approaches. The relief when it lands somewhere else. Patrolling. Our first patrol was down the hill we occupied and up the smaller, now-abandoned hill in front of us. It was spooky as we gingerly peered into the now-empty bunkers and trenches, always on the lookout for the dreaded landmines.

While moving our unit we had to spend the night outdoors. No tents, only sleeping bags. In the middle of the night it began to rain. It rained long and hard. My sleeping bag was soaked; my clothes were soaked; I was soaked—and cold. A creeping realization came over me that there was nowhere to go, no way to get dry no way to get warm in the blacked-out night.That sense of total physical misery has remained with me as a lasting memory of war.

John Hoskins, a lawyer, worked for the Agency forInternational Development and the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. He livesin Richwood.Ohio.

Rob Jackson '51

Second Lieutenant, U.S. Marine Corps I arrived in Korea in July 1951. There wasn't a lot of time to get oriented, as the moment we arrived I got assigned to a front-line platoon. One of the guys in our group was killed within 24 hours.

On New Years Eve 1952 I led a reinforced platoon attack just north of an area called Bunker Hill. A platoon is usually about 45 people or less, and I had about 62 that night plus a few tanks and guys carrying flamethrowers. We attacked an outpost. I was wounded by exploding mortar fire. Fortunately, I was wearing a recently issued flak vest. It kept most—but not all—of the shrapnel out of my body, and it did save my life. I got knocked down but was able to get back up, and I was later told that the attack was successful. About 30 percent were wounded, but fortunately only two or three were killed. We did what we were supposed to do, which was clean the enemy out of the outpost.

I never realized what my emotional involvement was until 1995, when I saw the Marine memorial in Washington, D.C., walking on up, watching the guys. At the very top of the hill the monument reads: "Freedom Is Not Free." It really got to me. The war was not a piece of cake, but we certainly did the right thing in Korea.

Rob Jackson worked in real estate for 42years. Helives in La Jolla, California.

Charles Storer '51

First Lieutenant, U.S.Marine Corps

During college I spent two summers at Platoon Leaders Class in Quantico, Virginia. The idea was that by the time I graduated I would be a second lieutenant in the Marine Corps Reserve, with no active duty unless there was a national emergency.Then North Korea invaded South Korea.

I was shipped to Korea in March of 1952 as an infantry platoon leader. In October my company was in a relatively quiet area on the main line of resistance. To our left was a promontory called the Hook, which had a commanding view. The Chinese army overran the Hook. The Marines fought back and got shot up pretty badly. We were about to try to recapture the Hook when our company commander suddenly got a bad back.The No. 2 man became company commander and I became the new No. 2. A guy named Rob jackson came in to take over my platoon. It turned out he was a '51, though I didn't know him at school.

We went up the Hook at night and were relieved to find that the Chinese had withdrawn. We were there about two weeks. At one point our new company commander was fatally wounded and I became company commander. I was called upon to get volunteers to reoccupy an outpost in the valley in front of the main line. We didn't know if there were any Chinese there or not Jackson volunteered, and he led a squad out there. It was a very gutsy move. He succeeded.

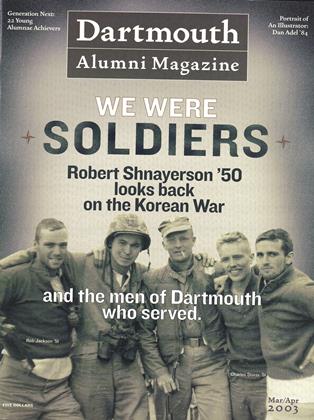

The photo [on the cover of this issue] was taken after we got off the Hook.

Charles Storer is senior director at the RobertMarston And Associates public relations agencyin New York .

Paul Woodberry 49, Tu'50

Second Lieutenant, U.S. Air Force

One afternoon in the spring of 1953, all the flight crews at Kimpo Airfield, near Seoul, were asked to attend a special briefing. The atmosphere was somber.The target map was covered up.The crowd filled all the chairs. We were surprised to see that the squadron commander and all the other brass were there. We wondered what was up.

Instead of an intelligence lieutenant, the operations officer, a major, addressed the crews. He was very serious and deliberate. He told us that the squadron had been asked to send a B-26 crew up the following night to try to get photos of the Sui-ho dam and hydroelectric power plant on the Yalu River. A jet plane had tried to get daylight pictures but was not successful. The dam and power plant were surrounded by 30 powerful-searchlights and had the strongest antiaircraft defense in North Korea.

The major explained that the squadron decided to ask for volunteers for this mission because it was unusually dangerous. He didn't mince words. In order to get complete photos of the dam and power plant, a B-26 would have to fly straight and level for several minutes at 8,000 feet. The searchlights could pick it up right away and it would be a sitting duck.

The major said that all crew members would be recommended for the Silver Star, whether or not they came back from the mission. He stressed that anyone who did not volunteer would not be criticized. He then said that anyone willing to volunteer for the Sui-ho dam mission should stand up.

All the pilots and navigators immediately stood up.

It was a proud moment for the squadron. All the crews had volunteered for the mission despite the obvious danger. The next day a Marine jet landed at Kimpo. It was shot up and badly damaged, but it had succeeded in taking daylight photos of the dam. Our mission was no longer required. But I will never forget that briefing.

Paul Woodberry, a consultant for Alleghany Corp.,lives in Hanover, New Hampshire, and Sea Island,Georgia.

Henry C. "Hank" Fry '53

First Lieutenant, U.S. Marine Corps Midway through my junior year I encountered some serious problems with one NROTC course: navigation. I flunked it. Twenty minutes later I joined the Marine ROTC program.

In Korea I was with a specialized military police unit patrolling the demilitarized zone. Both the Chinese and North Koreans moved the demarcation line around. One night a patrol I was accompanying did not follow the appointed azimuths and followed the demarcation line-we were actually 20 to 30 yards inside North Korea—and got caught. I feigned total ignorance and answered enemy questions in the broken German my college roommate Russ Smale '53 used to throw around. It puzzled the North Koreans, kept the physical abuse to a minimum and allowed me to rant, rave and complain without divulging any usable information.All in all, I was treated like the jackass they thought I was and was released some 36 hours later.

Henrry Fry works for Oslin Nation Inc. He lives inHouston, Texas.

Jerry Mitchell '51

Second Lieutenant, U.S.Marine Corps I went to Korea in August of 1951. From the air we did some spotting for the troops on the ground and the battleships offshore. We blew up rail tunnels, suspected depots. Around the end of August 1952 I was on a flight for which 1 earned a Distinguished Flying Cross. I was doing close air support on a ridge with three other planes. We made a number of runs on the troops down there, and toward the end of our 45 minutes flying around there one plane got hit, and we scattered. I lost sight of the other two planes. I tried to find out where the downed plane had gone; I found out later that the pilot had parachuted out safely I ended up landing at a dirt field almost to the border of the demarcation line. As 1 pulled off the runway the engine stopped running—l was out of gas. I was lucky. I put 15 more gallons of gas in my Corsair, then found out where I was on the map. Called my base, told them where I was and what happened, and they said, "Well, come on back."

When I came back to Dartmouth, in the early fall of 1952, a friend asked me what I had done. I said, "I got nine credits for being an officer and a gentleman, and six credits for learning how to fly. I spent my junior year abroad." Jerry Mitchell retired from Dartmouth Travel in2000 and lives in Hanover.

Robert Myers '50

Ensign, U.S. Navy I served on the destroyer USS John A. Bole, which spent parts of 1950 and 1951 in Korean waters. Most of our activities were plane guarding for carriers and shore bombarding. One of our main duties was delivering pilots back to their ships alter they had made bad take-otfs or landings. The destroyers didn't have icecream-making equipment, but the aircraftcarriers did, so we'd deliver pilots back to their ships in return for their weight in ice cream. We'd often be more interested in finding out how much they weighed instead of what condition they were in. "We've got a pilot here," we'd report, "one hundred and eight}' pounds. He's got a broken leg." Robert Myers worked for Rohm and Haas Co. inPhiladelphia, Pennsylvania, foryears. He lives inPoway, California.

Richard Paul '44

Major, U.S.Army

Just prior to Christmas 1950, my division, the 3rd U.S. Infantry Division, was assigned to evacuate the Marines, the 7th U.S. Infantry Division and the South Korean units from the beachhead at Hungnam. The U.S. Navy expertly provided fire support. At night the 16-inch shells of the USSMissouri were blazing giant red streaks among the lesser sizzling 5-inch shells of supporting ships. When Christmas Eve arrived, I stepped into a speedboat as the last man to leave the beachhead. I witnessed the handiwork of our engineers as the entire waterfront erupted in curtains of demolition.

That night I blessed the presence of our transport ship, with its sheets and hot showers.

Richard Paul taught Spanish and English at Culver Military Academy in Culver, Indiana. Helives in Destin, Florida.

Buck Scott '51

Second Lieutenant, U.S.Army Corps of Engineers For those of us like me who were students and admirers of the new United Nations (and in my case a supporter of the World Federalist movement), the war was a major test of political philosophy. I didn't run off during my concluding Dartmouth years to join up in a fervor of patriotism. Most of us were shaken at the thought we might be killed, and the consensus was that we would wait until we were taken. I spent my Dartmouth years protected from service because I was a fulltime student. By September 19511 was a volunteer in the U.S. Regular Army, on my way for infantry basic training. I thought: "Let's just face it. The fates will decide." As it turned out, the Army sent me on to Officer Candidate School for engineers.

I spent a number of months around the front in the mountains near the 38th parallel. I happened to be assigned to X Corps headquarters at Kwandae-Ri about 10 miles from the front line. Driving down the road you were vulnerable—you just didn't know if somebody was in the bushes or not. Fortunately I didn't have to kill anybody, because I was an engineer, but I can tell you, it's scary. Sometimes they'd send Piper Cubs from the other side and throw out grenades at our tents.

The truce came in July of 1953, and by October I was a civilian again. I have spent 50 years trying to put that war aside, yet it returns to confront me from time to time. It was a step in a direction I am convinced the world must go: to provide international resources for the conduct of global affairs, including the potential and actual use of force where rogue forces boil over. My part in the war was inconsequential, and the details of the fighting were pretty much like any other war. But our efforts in Korea deserve to be recognized if and when we face up to the need for global organization and action.

Buck Scott ran an electrical power business. Helives in Wynnewood, Pennsylvania.

Henry Nachman '51, Tu'55

Sergeant First Class, U.S. Army

I know the last place we were when the armistice was signed. It was on a place called Christmas Hill. July 27,1953, at 10 in the morning was when the war stopped—but not when the shooting stopped. We were told that the armistice would be signed at 10 but to keep our heads down because we didn't know what was going to happen. This was an armistice and not a peace. There was a 12hour "cooling-off period," and in those 12 hours there were more fireworks going off than there had been in the previous week. At 10 that night the shooting stopped. It was eerie.

The very last man who died in the Korean War, at 7:30 that night, was a sergeant first class, in my company. His name was Harold Cross. Recently my wife and I went to the Korean War Memorial in Washington, D.C. There is a data bank, and you can dial into it the name of any soldier who died in the Korean War. You get back a printout of a service record, a register, how they died. I dialed Harold Cross and it was deja vu all over again.

Henry Nachman worked in advertising and marketing in New York and now lives in Hanover.

John Hoskins '51

Buck Scott '51

Henry Nachman '51

Paul Woodberry '49

CASEY NOGA, a Dartmouth ReynoldsScholar, is pursuing a master's degree in MiddleEastern studies at the American University ofBeirut, Lebanon.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWomen on the Verge

March | April 2003 By Jennifer Kay ’01 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryRemembering America’s Forgotten War

March | April 2003 By ROBERT SHNAYERSON ’50 -

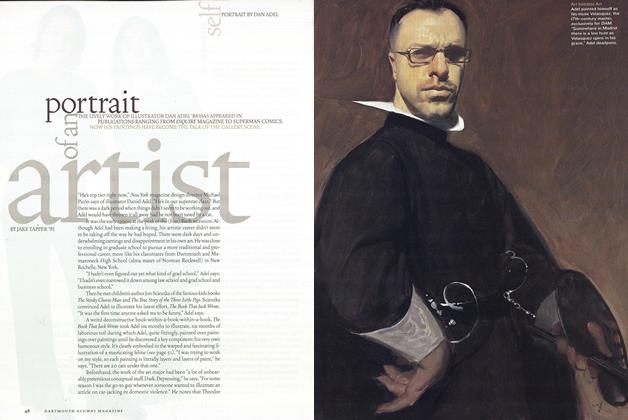

Feature

FeaturePortrait of an Artist

March | April 2003 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Alumni Opinion

Alumni OpinionLoaded Canon

March | April 2003 By Dinesh D’Souza ’83 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

March | April 2003 By MIKE MAHONEY '92 -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Cost of Winning

March | April 2003 By Professor Ray Hall

CASEY NOGA '00

-

Article

ArticleCatching Up

SEPTEMBER 1999 By Casey Noga '00 -

Article

ArticleReining Champs

OCTOBER 1999 By Casey Noga '00 -

Article

ArticleNatural Imperfections

OCTOBER 1999 By Casey Noga '00 -

Article

Article1951 Adopts 2001

NOVEMBER 1999 By Casey Noga '00 -

Article

ArticleNetworking

April 2000 By Casey Noga '00 -

Article

ArticleQuiz Kids

JUNE 2000 By Casey Noga '00

Features

-

Feature

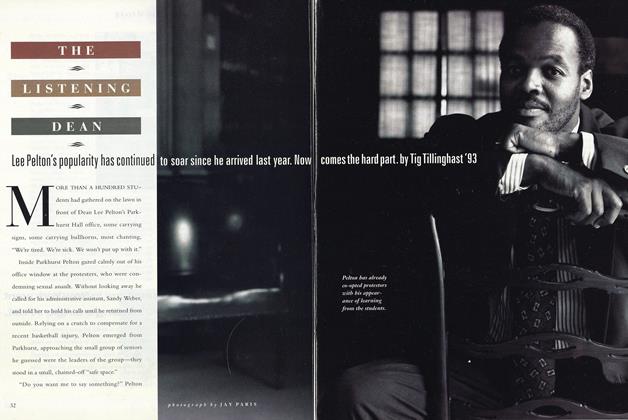

FeatureTHE LISTENING DEAN

October 1992 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryLONE PINE

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureNATO in Trouble

May 1960 By H. WENTWORTH ELDREDGE '31 -

Feature

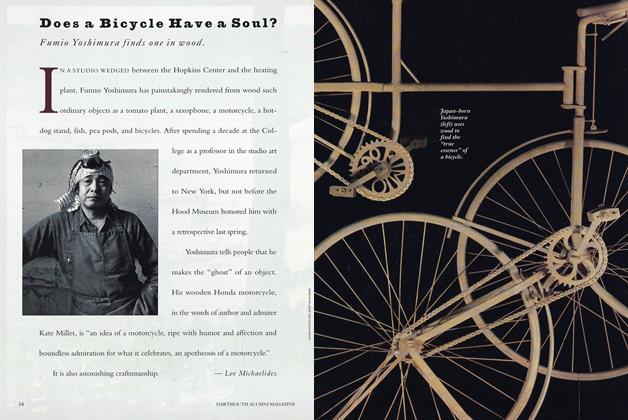

FeatureDoes a Bicycle Have a Soul?

June 1993 By Lee Michaelides -

Features

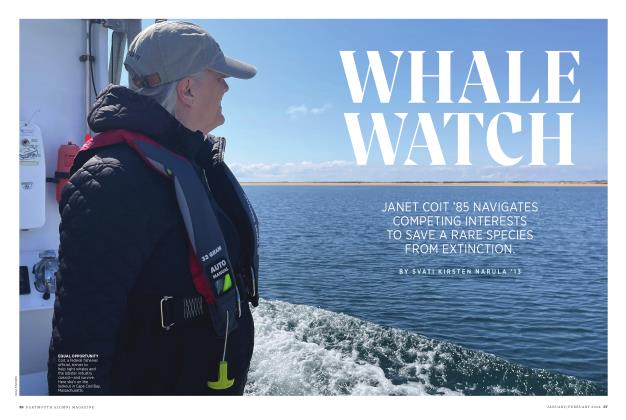

FeaturesWhale Watch

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2024 By Svati Kirsten Narula ’13 -

Feature

FeatureHYBRIS AND SOPHROSYNE

JULY 1970 By WILLIAM AYRES ARROW SMITH, LITT.D. '70