Barbering Studs-style

IT'S easy to start a lively conversation about barbers in Hanover. It's the rare male student who, during four years here, doesn't visit one at least occasionally. Everyone has his favorite shop and almost everyone has reasons for preferring one over the others. Sometimes the reason is simple vanity: "He's the only barber who can make my cowlick lie flat." Sometimes it's habit: "I've been going there for 37 years." And sometimes intangible but real attributes of a barber's character influence the choice: "So there I was, dozing in the chair, and suddenly he puts down the clippers, picks up a Bible, and starts a sermon about communism." A friend on the faculty recently confessed to me that he looks forward to visiting his barber because it's the only place he dares read the National Enquirer. A student told me he likes "the contact with the real world, the chance to talk with someone who isn't another student, professor, dean, or fan of John Anderson." An alumnus remarked this fall that one of the pleasures of attending football games and reunions in Hanover is the opportunity to see "if my barber still remembers my name. He always does."

I recently talked with a freshman, a city boy, about how he was getting along. "Those first couple of weeks," he said, "I made all the classic mistakes, like telling a barber that I wanted my hair short." Short is a relative concept. Ransom Ackerman, who sometimes works at Jim Grant's Hanover Barber Shop, told me not too long ago, "I used to cut a guy's hair and if he could pull it with his fingers it was too long." At the high school I attended out on the West Coast, only football players and swimmers wore what passed for short hair. The guidance counselor's impressions about Dartmouth, which neither he nor anyone else in my town had ever visited, were formed by the movie Winter Carnival, and the only advice he gave me about going to college here was to "get a Princeton nobody at Dartmouth has long hair."

Hair at Dartmouth has, in fact, been rather short in recent years compared to, say, a college like Reed, a particularly shaggy school I almost attended. But Hanover hair was long enough in the early seventies to send the local barber business into a severe slump from which it has just lately emerged. When I was a freshman, in 1971, I thought a trim a term was ample. Back in the golden age, haircuts every two weeks were taken for granted. As far as I've been able to discover, Henry Leavitt, a crew-cut local cop, is the only man in Hanover who gets his hair cut every week, and he's been known to come in twice within seven days. Unfortunately, as far as his barber is concerned, he's an aberration.

Most barbers in town will say they have nothing to do with promoting or discouraging a certain cut. They're after satisfied customers; your barber's happy if you are. They cut a head of hair the way it was cut before unless the customer asks for something different. (One of the players on the football team currently sports what might be charitably described as a pig shave with the numeral 100 carved into it, presumably standing for 100 years of Dartmouth football. I haven't been able to find out if a local barber was the accomplice.) Barbers certainly have their favorite styles usually, if they have a sliding scale of charges, the ones they make the most money on but generally, at least in Hanover, they are an agreeable and adaptable group, well deserving of the appellation under which they used to advertise: "Tonsorial Artists."

Pull some random issues of the Aegis off the shelf, take a look at people's hair through the years, and see how Hanover's barbers have had a hand in shaping America's leaders. In 1979, Joe College wore his hair halfway over his ears, parted on the left, and brushed across the forehead. There were a few closely trimmed beards and an occasional stray mustache. Many of my classmates in 1975 didn't have ears. A few had hair to their shoulders and the beards were bushier. Ten years earlier, there was a lot of what the barbers in town call the regular haircut short above the ears and enough on top to part and comb to the side. There were a fair number of Princetons, or Ivy League cuts, in 1965, but hardly a legitimate crew cut in sight. Back in 1958, however, crew cuts, straight up off the forehead, were everywhere. What 1949's seniors lacked over their ears, they made up for on top; lots of hair was combed straight back and lubricated liberally. The style was smoother in 1936, with less hair plastered closer to the bone. A fashionable fellow in 1920 parted his hair right down the middle, and in 1910 an early version of the dependable regular was in vogue. (Nicknames were also the style back then. A typical page in the 1910 Aegis identifies four serious-looking seniors as Frizzly, Goody, Hen, and Smilax.)

To find out about the long and mutually beneficial association between Dartmouth men and Hanover's hair dressers (that's how they're listed in old business directories), I spent months in research, visiting every barber in town. I talked with the professionals and I talked with people who have had decades of haircuts in Hanover. Before I begin with the specifics of my report, however, 1 ought to confess my biases 1 didn't take to barbers easily.

MY earliest experiences with hair were awkward, sometimes painful. I was born without enough of it to disguise two prominent bumps I still have on the back of my head (a phrenologist's dream come true). When my father first saw me in the hospital he said to my mother, "What's wrong with him? He looks like a hammerhead shark." Because my hair came in thin and blond, the top of my skull was often sunburned. The first barber I remember visiting used a wire brush, the kind commonly employed for scraping paint, for grooming my crew cut. On Sundays, the prow of that proud crew cut was dabbed generously with a rugged product called Butch Wax that came in a pushtube, like stick deoderant. The idea was to make hair stand at attention. Sitting squashed between my mother and my grandmother in a pew at church I would get hot and sweaty, and the wax would melt, running down my face into my eyes.

My father was a preacher, and one of his parishioners, a barber, thought it would be nice to offer our family free haircuts. No matter what they looked like and I was old enough to know they looked awful my father thought they were fine. His answer to my complaints about the barber's bad breath and annoying habit of giving my head a vigorous going over with the knuckles of both hands was to offer to cut my hair himself at home. After my mother obtained a set of shears with Green Stamps, my father's repeated and futile attempt to steer around my triple-cowlick left me embarrassed for days. Every night for months, just before going to bed, I subdued the haircut with hairspray and put on one of my mother's nylon stockings, cut off and knotted, as a kind of training cap. When I was finally able to choose my own barber, I selected the shop with the most provocative and educational selection of magazines.

As a sophomore in high school, after winning the battle over how long my hair could be, I met a junior named Sonja who specialized in cutting boys' hair in the bathroom at her home. Suddenly the home haircut was a good idea, no matter how it looked, and for the better part of a year 1 was getting clipped every other week. (Sonja's mother always supervised the proceedings from a perch on the edge of the bathtub.)

I drifted for a while in college but finally settled on a shop I patronized until the middle of my senior year. Everything went smoothly until the woman I eventually married told me on one of her first visits to Hanover to change barbers. The next day, as a farewell gesture (to the barber), I went in and asked for a butch, which I was alone in thinking contrasted nicely with my beard.

My new barber established on my first visit that I was a student, that I had once visited Alaska, and that I owned a wreck of an old car. Now, five years after graduating and with my future still in doubt, it's reassuring to walk into the same shop and to be asked how my studies are going, to hear how cold it gets in Fairbanks, and to talk about the failure of the automatic choke mechanism on a 1961 Mercury Comet. I hope my barber forgives the interlude of visits to his competition for this story. I'll be back. There's no reason to change.

BUT barbering in Hanover is about to change. Although there are more students there are fewer barbers, and many of the barbers who remain are thinking about retirement. Young men who want to cut hair see there is more money to be made with a license in cosmetology and an investment in a salon instead of a shop. Local rents keep going up and the shops are moving farther from Main Street. Ten years from now, you'll still be able to get your hair done in town, but you won't find much old-fashioned professional barbering, which at its best is more than just a haircut.

An expanded sense of the verb "barbering" met with some editorial opposition at the ALUMNI MAGAZINE when it was used by a writer reporting on commencement festivities last June. No less an authority than James T. Farrell, however, used the term in reference to the amiable palavering Studs Lonigan practiced at the local bar and poolroom. Barbering of this sort was at its height in Hanover back when John McCarthy, and later Louis LaCourse, ran their Main Street shop that boasted as many as three pool tables. Sources for this Harry Tanzi, Professor Emeritus Robin Robinson '24, former Admissions Director Ed Chamberlain '36, a couple of modern-day barbers, and several lesser authorities are in some disagreement over the exact location of the shop. It seems to have migrated from a basement location most recently occupied by the Tech Hi-Fi store, to the second floor of the same building, to the basement where Peter Christian's restaurant now more easily pays the rent. There is also disagreement about the total number of pool tables, the length of their tenure in the shop, whether billiards was also played, and whether shaving or snooker paid the bills. During the Prohibition era, another local barber, whose name was given to me in confidence by a source who wished to remain anonymous, was said to have moonlighted as a moonshiner, or at least as a distributor for a potent and potable version of Bay Rum.

Sad to say, Hanover lately seems headed down a boutique-and-corporate-head-quarters path. There is, for example, a women's-wear shop that calls itself, with apparent seriousness, Panache of Hanover, and a new building occupied by a large multinational corporation recently replaced the dark and greasy Inn Garage. The only pool tables are in fraternities. The kind of barbering Studs enjoyed will soon be slipping by.

Amos Blandin '18, former chief justice of the New Hampshire Supreme Court, remembers details of football games played his freshman year but confesses he has no memory at all for barbers. He sent me over to talk with Harry Tanzi. (For the benefit of several thousand relatively young alumni, Tanzi is perhaps Hanover's most celebrated character, known in particular for his creative use of facts when telling a story. He and his brother ran a store, owned before them by their father Angelo, noted for the freshness of the produce and of the help. It was the kind of place that occasionally had its license to sell beer revoked.)

Tanzi's memory of barbers in town stretches back to the days before World War I. He said there was a shop over the old Dartmouth Bookstore (which was located near the Casque and Gauntlet house), owned by a barber named Ed Dewey, "who wouldn't wait on people he didn't like, and he disliked quite a few." A barber whose name might have been Ed Orral also had a shop in town, Tanzi says, but he can't remember where the shop was. He might be thinking of M. M. Amaral, who is listed in the 1888 Hanover directory as a hair dresser working on the Emerson block, and who might still have been in business after the turn of the century. The same directory shows that John McCarthy, who was succeeded by Louis LaCourse, also ran a livery business in addition to his barber shop. Tanzi aiso recollected that Barber Fred Michaud owned a fancy horse and buggy; that Bill Brock branched out from barbering to become "Hanover's first real estate broker, a sharp operator and very wealthy when he died"; and that Dick Stone was another barber who had pool tables to supplement the tonsorial business in his shop next to Tanzi's store.

As Tanzi remembers, there were at various times barber shops over what is now the Village Green (Michael's presently does a hair-styling business upstairs), over the old Allen's Drug Store ("the longest soda fountain counter in New England"), possibly a shop over the Hanover Hardware store, and in a building that occupied the Dartmouth National Bank's present location. Trottier's predecessor on the second floor of the building Lou's Restaurant occupies was Joe Damato. Dad Bowman's Hanover Inn Barbershop employed Walter Chase (later the proprietor of Walt and Ernie's), Tanzi's brother-in-law Tony Cacciappo ("he could do anything"), and, according to a different source, an ex-cop and ex-boxer named Syl. Some people also say that Ernie DeRoche began his long association with Walt at the Inn. According to the 1921 equivalent of the Yellow Pages, haircuts could be had in town from Eluzar Misho on the Bridgman block, from John McCarthy on the Musgrove block, William Brock on the Davison block, and from William Bowman.

Bowman figures most prominently in the recollections of several generations of alumni who patronized the shop located on the Main Street side of the Hanover Inn, approximately where the Inn's gift shop is located now. Charlie Widmayer '30 former editor of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE, recalled that toward the end of the elderly Dad Bowman's long career, "his hands shook a little." After the Inn Barbershop closed, Widmayer stayed with Dad's associate Tony Cacciappo, who started a shop on the second floor of the Lang Building (above Campion's) in 1936 and who was succeeded upon his retirement in 1957 by another brother-in-law of Tanzi's, Jack Roberts. Still in business at Tony's, although in a different second-floor location, Jack "is a great conversationalist," Widmayer pointed out. "We inevitably talk about car repairing."

Ed Chamberlain, a regular customer of Walt and Ernie's, also mentioned Bowman's tremble. It apparently made quite an impression: "Toward the end, most people decided to avoid having him do the shaving." Jim Farley '42, a long-time local journalist, presently the assistant director of the College News Service, is also a Walt and Ernie's man with fond memories of Bowman. "Dad was a man of some years, probably old enough to have cut President Bartlett's hair certainly President Tucker's hair. He had a nervous quiver in his hands, but as soon as he took hold of the tools of his trade he stopped shaking and, as I remember, did a fine job." Like Bowman, Walter Chase continued to cut hair until he was an old man, Farley added. "Even in his seventies, he was a fast and skillful barber. Once when I was in a hurry to catch a bus, he gave me a crew cut in five minutes." Farley "never went to Tony's, but that was the gossip center in town. He was quite a character, like his relatives the Tanzis. He knew everyone, whether he cut their hair or not."

Back when there was more often a waiting line in barber shops, Chamberlain would play the field. "For a short time I went to Pinkie Lunt, a local guy who tried, unsuccessfully, to sell things on the side. The students knew him pretty well. He ended up delivering telegrams, I think. Louis LaCourse, who was quite a Main Street character, also ran a pool parlor along with his barber shop, but that was mostly for townies. Dick Stone was a famous barber, and I went there occasionally, but his shop was often closed with a sign saying 'gone fishing' or 'gone hunting.' His original partner, Bill Brock, gave up barbering to attend to his real estate investments. He was very successful owned his own sewer system and named several streets."

"In those days," Chamberlain continued, "the shops were all pretty much alike, except for Tony's, which was a little bit fancier, more genteel. A few of the barbers liked to drink a bit. For the most part, they were conservative fellows, local guys against things like any increase in taxes. They were interested in athletics. The Police Gazette was standard reading material, along with the Boston Post and the Herald never the New York Times. Conversation was on a masculine, lockerroom level of chit-chat. Over the years since Walt and Ernie left, I've been good, jovial friends with Bob Trottier and Carley Massey, who run the shop now. There are still a few old-timers who hang around. What you talk about depends on who is in there. Sometimes it's local or national politics, seasonal sports golf in particular, or hunting. If something has been happening on campus, you might get ragged about the students at the College."

Bob Trottier (not to be confused with his cousin Theodore, another Hanover barber), who started in Hanover three years after his associate Carley joined the shop in 1954, told me that for years after retiring, Walt would come back to Hanover during reunions to see his old customers. "He couldn't tell you what he'd had for breakfast, but he could remember the names of people whose hair he cut 25 years ago when they were un- dergraduates." Several decades ago, shortly after the death of old Mr. Putnam of Putnam's Drug Store, the shop's last regular shave customer, Walt and Ernie's advertised on the window the policy of giving "No Shave." Students soon made "No Shave" part of the shop's name, sometimes a substitute for the name, such as when they made out the blank checks Walt kept by the register. A year or two ago, when students complained after the peeling No-Shave sign was scraped off the window. Bob and Carley hired a senior art major to paint it back on. He didn't do a very good job, but at least tradition was preserved.

"The College community has been the backbone of our business," Bob said recently, "but the era of long hair cut our business by half. It used to be that people were lined up in the morning before we started work. All day long there was no such thing as catching up. Styles have changed and business has picked up again over the past couple of years. But it used to be that you got a haircut every two weeks no matter what. Now it's once a month for a lot of people, even your professional people."

Robin Robinson started going to John McCarthy's Hanover Barbershop as a freshman in 1921. A haircut cost 25c the whole time he was in college. During a recent conversation he remarked that "when I went to Cambridge for graduate school, I was horrified to find it as high as 50£, so I shopped around until I found a place where I could get it for 350. Now I pay $2.75. The other day I visited the shop, which is presently owned by Jim Grant, who started cutting hair here in 1963, and absentmindedly paid him only $2.25. He didn't say anything, and he wasn't going to, either. I only realized my mistake as I walked out the door. What keeps me going to the same shop all these years? Why change? I always have interesting conversations with Jim, the son of a former history professor at Williams. I don't have to tell him not to shave behind my ears. I've never had any discontent with the service, and I feel a loyalty to the firm. I once thought that if I ever did change I'd go to Walt and Ernie's because Walt's wife once worked in the freshman commons when I was an undergraduate."

Although the furniture and fixtures in Grant's shop date back to the days of the previous owners McCarthy and LaCourse, several of his other regular customers have remarked that it's not the shop's atmosphere, or the conversation with Grant, that attracts their trade, but rather his abilities as a barber. He got into the business because he likes people, Grant told me, and barbering seemed like something he could devote his life to. After training in Boston, "down in the Combat Zone," he went to a hair-styling school in Manchester, New Hampshire, and now offers every kind of service from styling to shaves. He's the youngest barber in Hanover and the only one willing to scrape faces with a straight razor.

Sharing his thoughts about the barber business, he noted that "there's one thing that's new, and that's facials. Then you have your shaves. And they come and go. So basically, it's what's 'in' now that you have to do. But you also have to have your various kinds of trims, you know. So you have to be experienced in all angles and do your best at it, basically. Because everyone's different. Our rates go from $2.75 to as high as $7.00 depending on the type of cut. But you can't force a style on anybody. I try to go by what people want. That way they're not put on the spot and they're not dissatisfied. We have 75 per cent students. Back in the sixties we gave a lot of military haircuts because of R.O.T.C. The Vietnam years were bad. Nowadays they like it short, but they don't like to be scalped. It's at the top of the ears or slightly over. In the 1970s the Dartmouth fellows have improved over 100 per cent. In getting along with people. A hell of a lot politer and more intelligent than in the sixties by a long shot."

Up the street at Tony's, Jack Roberts once had three barbers working for him, with only a shade less work to do than when Tony Cacciappo had five chairs there, including a special chair for cutting women's hair. Then the new longer styles hit and business dropped off. "Pretty soon," Jack explained, "it was just Manuel and I here, and he passed away four years ago. He worked this shop for 28 years. He was a genius of a barber, and he could do any kind of work, here in the shop or at home. He could do anything with his hands.

"As it is, I have enough work as I should do. I'm old enough to retire, but after you raise five children and put them through college there's not much left to retire on. I still enjoy doing the work, and I've got customers I've been serving more than 30 years. When you do these people that long, you almost feel you owe it to them to continue. It bothers me to take a day off because of missing people. Back in the days when people got a lot of haircuts, two-thirds of my business was college students. Now its about half. The early seventies were the slowest, and 1972 was the bottom year. Back then we did boys' camps and private schools on the side. We went to seminars to learn the new styles, and I tell you we appreciated it when customers came in the door. Then things started to pick up again. I came here in 1946 and I've always had a classy clientele. Nelson Rockefeller got his hair cut from Tony and he used to come back and visit when he was in town. This has been a good town. I've never had but one person drunk in this shop."

Theodore Trottier, proprietor since 1951 of the shop people call Trott's, was my most loquacious informant. He's famous for his garrulity, and his interests stretch from religion to economics. The average barber's reputation as a talker isn't really deserved, he explained. "Barbers aren't naturally talkative. The customers are the ones who make the barbers talk. If they leave the barber alone, he won't talk at all. If I'm busy, that's the way I prefer it, but I will visit if I have the time."

MY last haircut for the purpose of this report was also the occasion of my first visit to an out-and-out stylist, a beautician, at a unisex salon the Hair Affair on Lyme Road. It's a classy shop, designed by a decorator from the looks of it, with a receptionist, fancy contemporary furniture, wood-paneled partitions, potted plants - but not a copy of SportsIllustrated in sight. Becky, who sometimes cuts my wife's hair, saw through my assumed nonchalance and figured right off that I'd only been to barbers before. "About 40 per cent of my business is men," she reassured me. She led me behind a partition, sat me down, ruffled my hair with manicured fingers by way of inspection, and propped me in front of a sink for a shampoo. Then she cut my hair while it was still wet all careful scissor and comb work, no clippers. An attractive and engaging professional, Becky moved north from Pennsylvania a couple of years ago for the skiing. She gave me a dandy do, maybe the best I've ever had, but I don't think I'll be back. The way I see it, if a guy can keep his hair out of his eyes and off his ears for under $4, and if a barber can camouflage a cowlick, why pay more for something slick? It's more than just a haircut you get at a barbershop, it's professional barbering - the kind of barbering Studs Lonigan could appreciate - and a person might as well enjoy it while it's still around.

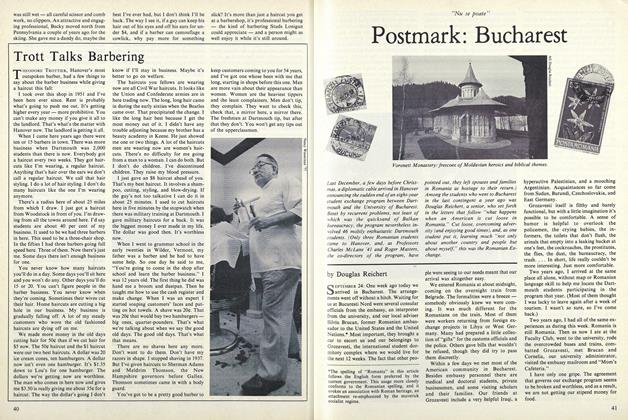

Eleazar as he was - bewigged - and as he might have been - bewhiskered - in 1880.

Eleazar 1920s-style, slicked and center-parted, and in 1949 with a pompadour.

By 1955, he might have resembled Mickey Spillane; by 1970, the boy next door.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureNow Let Him Praise Emmets

November 1980 By Robert Sullivan -

Feature

FeaturePostmark: Bucharest

November 1980 By Douglas Reichert -

Article

ArticleTrusteeship and the Alumni

November 1980 -

Article

ArticleUnofficial Arbiter

November 1980 By Patricia Berry '81 -

Article

ArticleWanted: Road-trip Messerly

November 1980 By Parker B. Smith '66 -

Article

ArticlePolicy Manager

November 1980 By M.B.R.

Dan Nelson

-

Feature

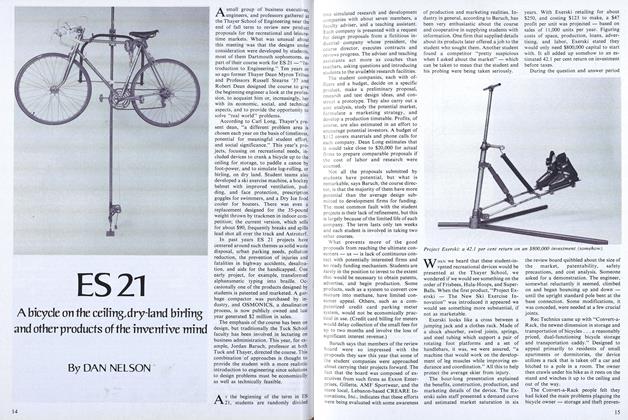

FeatureES 21

January 1977 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

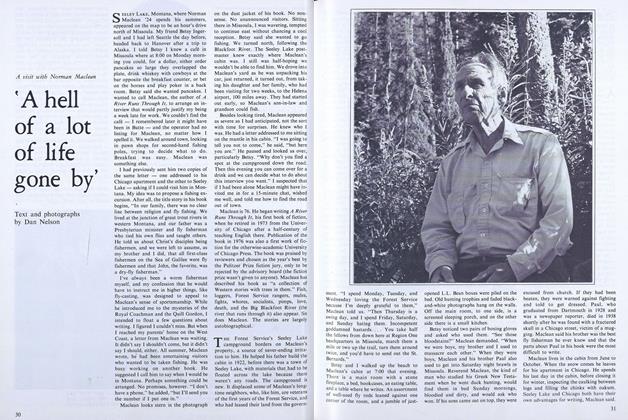

Feature'A hell of a lot of life gone by'

November 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureThe Trustees: 15 men and a woman with ultimate authority

October 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureUncle Sam and Mother Dartmouth

November 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

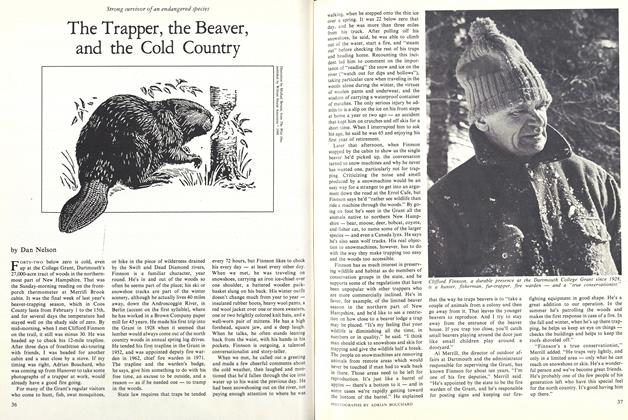

FeatureThe Trapper, the Beaver, and the Cold Country

March 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Two Worlds

May 1980 By Dan Nelson

Features

-

Feature

FeatureArcheological "Amateur"

October 1973 -

Feature

FeatureCue the Millennium

NOVEMBER 1996 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"Be Prepared For The Unexpected"

Mar/Apr 2009 -

Feature

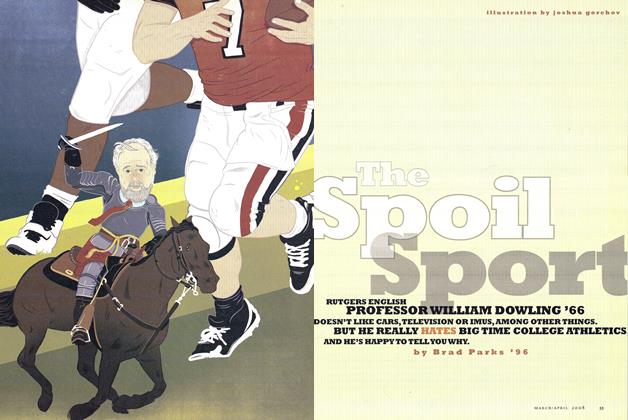

FeatureThe Spoil Sport

Mar/Apr 2008 By Brad Parks '96 -

Feature

FeatureArms Control in a Cold War

May 1961 By GENE M. LYONS -

Feature

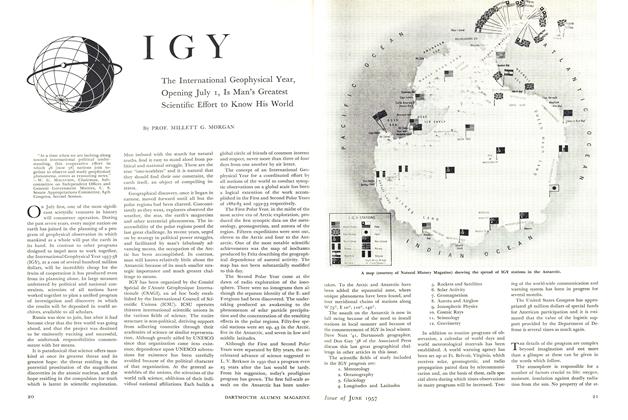

FeatureIGY

June 1957 By PROF. MILLETT G. MORGAN