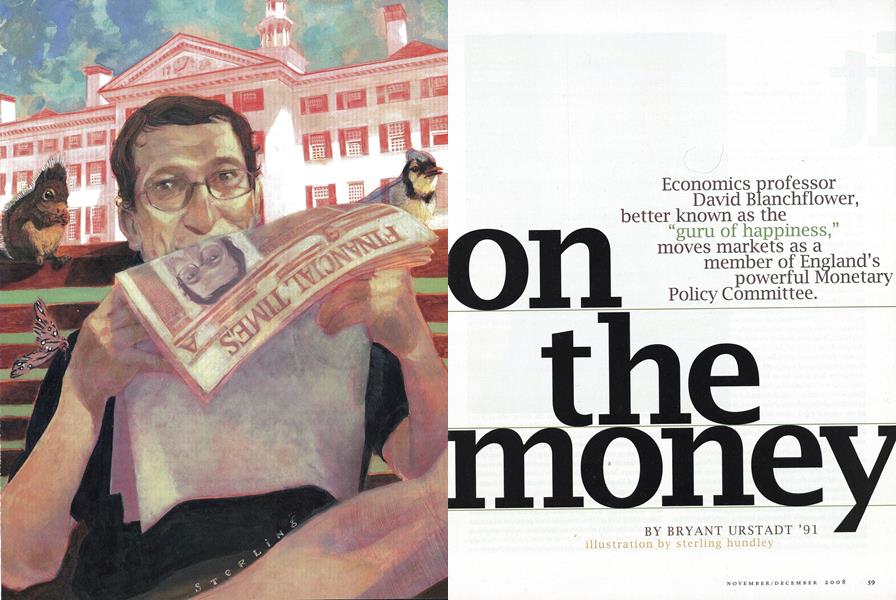

On the Money

Economics professor David Blanchflower, better known as the “guru of happiness,” moves markets as a member of England’s powerful Monetary Policy Committee.

Nov/Dec 2008 BRYANT URSTADT ’91Economics professor David Blanchflower, better known as the “guru of happiness,” moves markets as a member of England’s powerful Monetary Policy Committee.

Nov/Dec 2008 BRYANT URSTADT ’91Economics professor David Blanchflower, better known as the "guru of happiness," moves markets as a member of England's powerful Monetary Policy Committee.

It took about 10 days for David Blanchflower to go from a respected professor on the Dartmouth campus, studying the rather fringe subject of happiness, to a major player in the global economy—and a figure so often discussed that the Colleges public relations department at one point gave up efforts to track news reports mentioning his name. He is currently on the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the Bank of England, which means he helps set the interest rates for one of the worlds largest and most influential economies.

Not that students in Hanover are throwing palm fronds before him. "I don't think most people have much of a clue what I do," says Blanchflower, who walks the campus in relative anonymity. Meanwhile, in England, his every move and utterance is reported in the press.

Blanchflower, 56, the Bruce V. Rauner '78 Professor of Economics, has been teaching at Dartmouth since arriving from his native England in 1989. He is a labor economist. As he describes it, a labor economist thinks about the market for people, how you motivate them, what the distribution of income looks like, what the rates of return for education are, that sort of thing.

One of the things Blanch flower thinks about is how national and local economics affect happiness. The results of his research are often picked up by radio and magazines, which love little factoids, such as the one that suggests a marriage is worth approximately $100,000 in income, or that, as he wrote in one paper, "the happiness-maximizing number of sexual partners in the previous year is one." But more on all that—and why you're happier with your new BMW if your neighbor doesn't get one, too—later.

As of the winter of 2006 Blanchflower was still a typical professor, working out of a plain office in Rockefeller Hall. Talking there in late May Blanchflower looks a lot more like a professor than a mover of markets. His nickname is "Danny," after Danny Blanchflower, a famous English soccer star of the 19605. Wearing a polo shirt, slacks and comfortable shoes, he appears to be a man on the way to the golf course, which he might have been. He is a passionate golfer who claims a 7 handicap and is a member of the Royal Dornach Golf Course in Scotland, one of the founding courses of the sport.

"The College always lets you know when there's something written about you in the press somewhere," says Blanchflower, speaking in an English accent ground down by years in the States. "I was in my office, checking my e-mail, and I got a story sent by public affairs that ran in the Financial Times, which noted that I was one of three candidates to join the Monetary Policy Committee of the Bank of England. A couple of weeks later I got a call."

It would be roughly like seeing an item in the paper mentioning tioning that you might be joining the board of governors of the Federal Reserve. The MPC is a nine-member board that sets the interest rate maintained by the Bank of England. Nominees are scrutinized like tea leaves by economists, investors, market makerd, politicians, journalists and just about anyone with an eye on the British economy. It is, in the words of more than one economist, a "huge deal."

Ten days after the call, on March 22,2006, Blanchflowerwas a member of the committee, officially appointed by the chancellor of the exchequer, Gordon Brown, now prime minister. Brown and his staff choose the members without any explanation about how the process works, so even Blanchflower isn't really sure how they came to select him.

And even if he did know, he couldn't talk about it.

A few times during a recent conversation he spreads his hands and suddenly says, "I can't answer that. It's market sensitive, you know." Particularly off limits is any discussion of the future, especially as it relates to the direction of interest rates. But he is free to discuss past decisions and data about where the economy is, though not where it's headed.

His term began on June 1,2006. The whole thing happened so quickly that the British press, never shy about offering up criticism on topics ranging from the prime minister's views to author Martin Amis' teeth, raised questions that the appointment had happened too quickly. Even Blanchflower admitted he was "shocked" by the speed of the process.

Recounting his transformation from academic grind to financial powerhouse, Blanch flower frequently mentions how important the position is—and how much fun he's having. The exchequer's office actually told him the position would be "boring," but it has been anything but, with the credit crisis acting like an "earthquake, a big momentous event," says Blanch flower. "It's really hard for everybody to figure out what's going on." The power is not boring, either. "I make a decision and the market reacts," says Blanch flower. "It's pretty awesome. I made a comment once and the yen moved."

As an appointee he has been a tenacious loner, arguing for decreases in the interest rates and frequently voting against the majority. He often finds himself on the losing side of 8-to-1 votes. The Sunday Telegraph has called him "the maverick bloom in Browns garden."

In a banker s terms, that makes him a "dove," meaning that he has wanted to see interest rates go down. "I have tended to take the view that there's more slack in the economy than other people have," he says, "and that might drive the economy into a recession. The United Kingdom looks very much like the United States did 10 months ago."

This June, for example, the committee voted to maintain rates at 5 percent. The vote was once again 8-1, with only Blanch flower voting for a cut, this time of 25 basis points, or .25 percent. Though he has often voted alone, he believes public opinion, at least, is coming around to his point of view that a recession and hard times loom. "He is not the boy who cries wolf," wrote one commentator in the Independent.

"One thing you have to know about David Blanch flower," says colleague Richard B. Freeman '64, a labor economist who teaches at Harvard and spends part of the year as a senior research fellow at the London School of Economics and Political Science, "he's feisty."

Part of Blanchflower s track record may have to do with his profession. As a specialist in wages, he is less concerned with the stability of the pound than with the standards of the wage earner. "I'm concerned with the real economy," says Blanchflower. "The real economy is about what happens to real people. If unemployment goes up 1 percent, that's a number, but real people are really affected."

Or as he told The Guardian after the committees January vote, "Worrying about inflation at this time seems like fiddling while Rome burns."

Says Freeman, "If you brought his name up in a working-class pub in England and the folks you're with knew who he was, they'd raise their glasses and say, 'Here's to Blanch flower and may he screw the bastards!'"

Blanch flower divides his time between Hanover and London. Though there were early questions in the British press about whether his schedule was somehow too indulgent—either in terms of carbon cost or just plain expenditure on the part of the exchequer—it seems to be working. He's currently on leave from teaching, although he does drop by Econ 22: "Macro" on occasion to talk about his work on the MPC. When he was teaching he focused on labor economics, advanced labor econom- ics, statistics and econometrics. When his term ends in 2009 he expects to return to teaching, although former members of the committee are generally regaled with offers from banks, hedge funds and universities looking for presidents. (Stephen Nickell, who preceded Blanchflower, is now the "warden" or president of Nuffield Col- lege at Oxford University, which is a little like becoming the dean at Tuck. Howard Davies, who served for less than a year in 1997, is now the director of the London School of Economics.)

Blanch flower typically arrives in London a week before the MPC announces its monthly decision, which happens on the first Thursday of every month. He shows up at the Bank of England the Friday before for an initial meeting at which members request numbers and research from staff. From that day until the following Friday, after the votes have been announced, the committee is isolated. On the Wednesday before the announcement the committee meets at 3 in the afternoon. "We meet for three hours and argue and debate," says Blanch flower. Thursday at 9 a.m. they meet again and vote. Results are announced at noon. Then the markets move.

At work Blanchflower is surrounded by all the grandeur of old England. Originally the bank of the government, the Bank of England is now the central bank of the British banking system as well. Blanchflower and his colleagues meet in the Centre Room of the Bank of England under a stern portrait of former bank govermnor Montagu Norman. He works out of a woodpaneled office with windows overlooking the Royal Exchange and The Mansion House, where the Lord Mayor of London lives. The basement holds a good portion of the country's gold reserve, in the form of stacks upon stacks of gold bars, sagging under their own weight. "I got to go see them," says Blanchflower, betraying a bit of boyish excitement about the perks of the position.

It's all an odd turn for an economist best known to the public for putting a price on sex. Until his appointment to the MPC Blanchflower was mostly quoted on the economics of happiness, which has made him somewhat of a media darling.

In their 2004 paper "Money, Sex and Happiness: An Empirical Study," Blanchflower and Andrew Oswald, a frequent collaborator, surveyed 16,000 adult Americans and found that sexual activity enters "strongly positively" in happiness equations. "We calculate that the median American has sexual intercourse two to three times a month," the abstract clinically notes, "the happiness maximizing number of sexual partners in the previous year is one," and "men who paid for sex are considerably less happy than other people." In their efforts to find out what makes people happy, and how that is related to income and the economy, Blanchflower and Oswald compiled a list of 19 daily activities. Sex ranked at the top in adding satisfaction to a life; commuting came in at the bottom.

Oswald is a professor of economics at Warwick University in Coventry, England, where Blanchflower used to teach. They have worked together since 1984. Their 1994 book The Wage Curve argued that low unemployment corresponds with high wages, contrary to prevailing economic theory, though seemingly in line with common sense. Probably more important to economists, TheWage Curve has received a fraction of the attention of the sex and happiness scholarship. The Wage Curve is a major work, though, in computing time, as well as in scholarship. Blanchflower and Oswald estimate they used around 9,000 processor hours crunching numbers at Dartmouth, equivalent in 1994 to about $2 million in commercial computing time.

Sex forms just a portion of the pair s work on happiness, which ranges widely over the subject from helping to define the famously loose term as a useful gauge to trying to figure out how it increases or decreases in a group of people. Blanchflower has crossed over into psychology, believing that department has a lot to offer an economist. He has even studied the physics of the smile, differentiating between a fake smile and a real one."I tend to the view that interdisciplinary things matter," he says about his trips to the psych department. "They know stuff that we don't, and I tend to talk to them more than to other economists."

Blanchflower and Oswald's Paper, "Well-being Over Time in Britain and the USA," found declines in happiness in the United States during the last 25 years, particularly among white women, while happiness rose among blacks. The least happy tended to be those separated from their spouses or widowed. Performing a form of "happiness calculus, they argued marriage gives one the same amount of happiness as an extra $100,000 a year in income. Unemployment, meanwhile, subtracts about $60,000 in happiness, all things being equal. That may sound strange, but according to Blanchflower s calculus, it means not being able to find a job is so depressing it would take roughly $60,000 a year to ameliorate the feeling.

The paper argues that not only does money buy happiness to some extent, but that happiness also tends to spread itself out in a U-shaped curve across the average persons life, with higher levels of happiness at the beginnings and endings of life. The bummer years for U.S. residents seem to be the late 30s, as early, very high aspirations either go unmet or, worse, are achieved by others.

It's hard to watch others succeed because happiness, the authors say, is very much a relative event. A friends success can be as painful as personal failure, as we tend to look up and not down when trying to situate ourselves on the socioeconomic ladder.

"If I get a new BMW," says Blanchflower, "my happiness is greater if you don't get one." Experiments have found that subjects would rather have five of something when everybody else gets one than six of something when everybody else has five.

Later in life happiness increases again as one sheds or meets those aspirations and as competitors die, which seems to provide, statistically anyway, a bracing and welcome shower of well-being on the survivors.

The study of happiness has, naturally, been attacked by all kinds of grumps. The Financial Times, for one, sniffed at Blanch flowers happiness research upon his MPC appointment, saying that he had "strayed into the esoteric." The Sunday Telegraph has referred to him as an "oddball and so-called happiness guru. Others just scoff at the notion of math or statistics having anything useful to say about as slippery a notion as happiness, for who hasn't spent time trying to figure out if they themselves are actually happy or not, much less narrow it down to answers applicable to multiple-choice questions?

Part of Blanchflower's work has been devoted to addressing those questions. "We've been trying to correlate reported happiness with objective real things," he says, again returning to his emphasis on the "real." It turns out, for instance, that higher levels of happiness correlate with lower blood pressure, better results on EKGs and less heart disease overall. (Of 16 nations he surveyed, Denmark and the Netherlands are statistically the happiest and enjoy the lowest blood pressure, while the Italians and the Germans seem least happy.) It also turns out that reported happiness correlates very well with these and other factors. A wife, for example, is likely to judge correctly that a happy husband is in fact happy.

And all this can help with setting interest rates, too. More jobs, to summarize Blanchflower's view, make people happier than does low inflation.

When he is not studying the value of happiness-or setting the interest rates for the Bank of England Blanchflower is often playing golf. He has been a faculty advisor to the Dartmouth golf team for 15 years. He took the team to his club in Scotland in the 19905. True to form, many of his golf proteges have gone into finance, and he hears from many of them, although not all agree on the direction he's been taking. When asked how many e-mails he gets a day, he seems to consider for a moment whether it might be market sensitive information and then throws up his hands, saying, "I don't think I should say.

Lately Blanchflower has been looking into topics such as self-employment among minorities and the impact of affirmative action programs. He has found that self-employment is directly related to capital, and that minorities in general and blacks in particular are more likely to have loans denied and pay higher interest. As with his happiness work, the economist does not publicly take or advance positions related to these findings but merely offers them up as data to be used by others in the policymaking business. He has called his approach "the economics of walking about." It's a phrase meant to suggest that he likes to look at things on the ground rather than through a theoretical lens. It's also a caution to economists to make sure their decisions do the least harm. One of his mentors, he says, used to tell him to worry about the welfare of "the man on the Clapham omnibus"—the reasonably educated and intelligent but non-specialist person.

He has done his best to heed that advice. "One of the big things I'm interested in," says Blanchflower, "and what should be the ultimate purpose of economic policy, is how to make people better off."

Maverick Bloom The economist often finds himself voting against all eight other MPC members.

Blanchflower has crossed over into psychology,believing that department lot to offer an economistHe has even studied the physics of the smile.

BRYANT URSTADT is a freelance writer and contributing editor for DAM. He lives in New York City.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

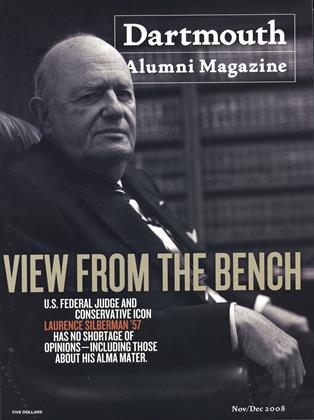

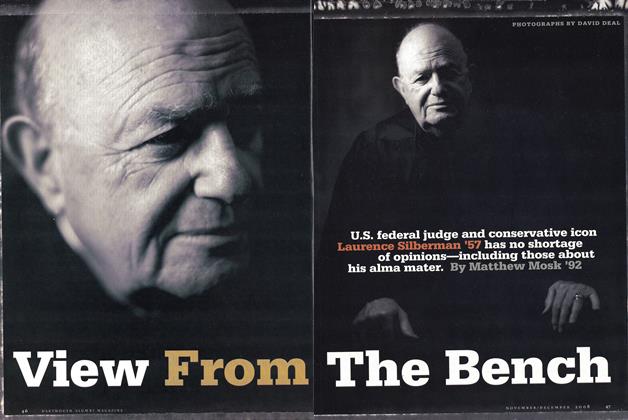

COVER STORY

COVER STORYView From the Bench

November | December 2008 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

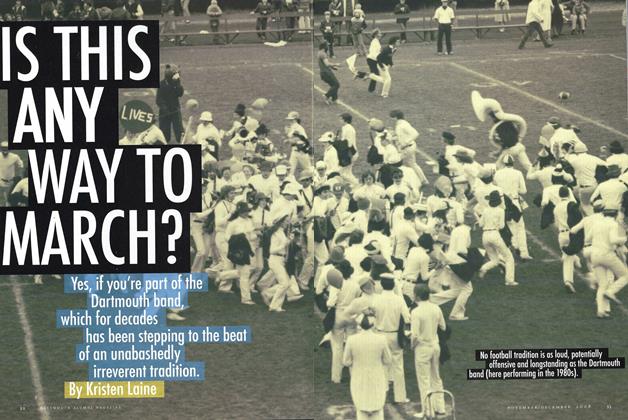

Feature

FeatureIs This Any Way To March?

November | December 2008 By Kristen Laine -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

November | December 2008 By TIM FITZGERALD -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

November | December 2008 By Bruce Beasley '61 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYA Vicious Cycle

November | December 2008 By Latria Graham ’08 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTELuck of the Draw

November | December 2008 By Bryant Urstadt ’91

BRYANT URSTADT ’91

-

Feature

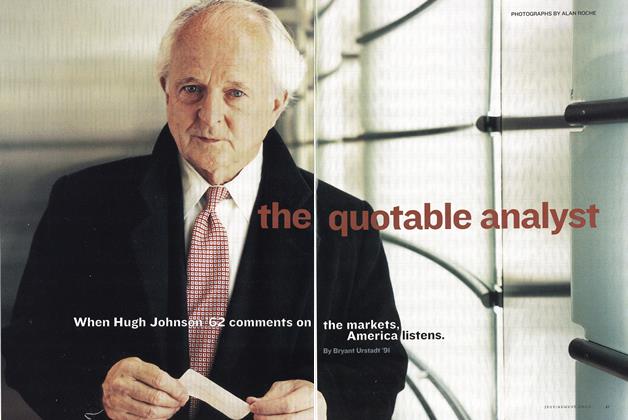

FeatureThe Quotable Analyst

July/Aug 2002 By Bryant Urstadt ’91 -

Sports

SportsHuge Specimen

Nov/Dec 2003 By Bryant Urstadt ’91 -

Feature

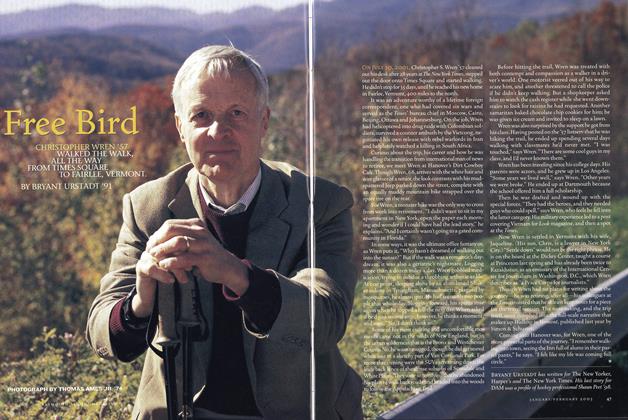

FeatureFree Bird

Jan/Feb 2005 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

Feature

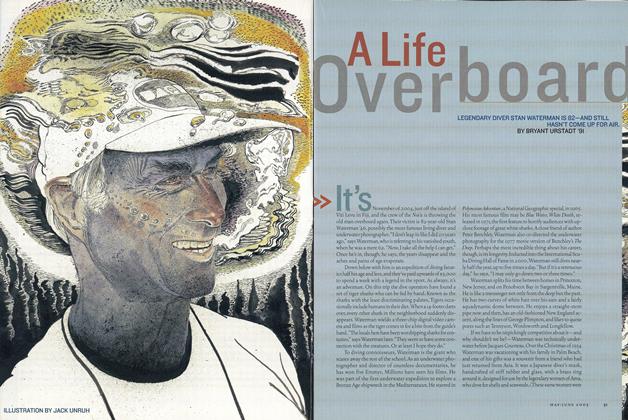

FeatureA Life Overboard

May/June 2005 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

OFF CAMPUS

OFF CAMPUSShrimp, Sirloin, Sass

July/August 2006 By Bryant Urstadt ’91 -

Feature

FeatureCold Warrior

Jan/Feb 2008 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91

Features

-

Feature

FeatureAlumni Awards

FEBRUARY 1971 -

Feature

Feature'... A whole pool of frustration, anger, resentment...'

February 1976 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryAn Insider's Guide to the World

October 1995 By Dawn Conner '95 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryM. Lee Pelton

OCTOBER 1997 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Feature

FeatureAt Dartmouth, the Intellectual Is on the Margin

MAY • 1988 By Karen Avenoso '88 -

Cover Story

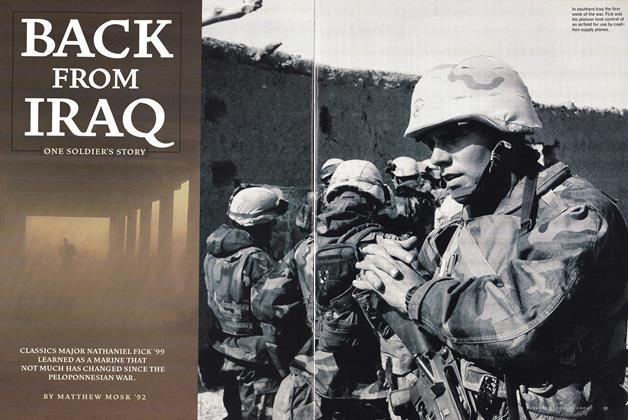

Cover StoryBack From Iraq

Jan/Feb 2004 By Matthew Mosk ’92